Mechanics solution manual

January 22, 2009 at 10:45 PM by Dr. Drang

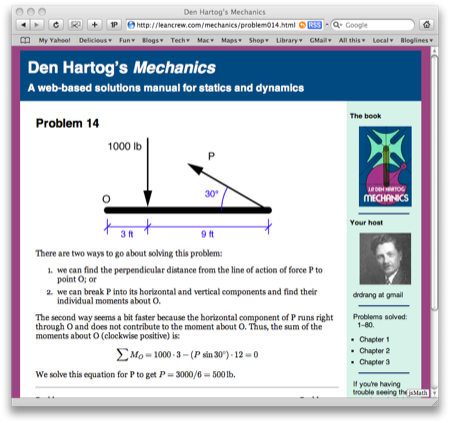

A few years ago I had a second blog, the goal of which was to provide a solution to every problem in J.P. Den Hartog’s Mechanics textbook. I stopped updating the blog after about six months, for reasons I’ll discuss in a bit, and eliminated it entirely a year ago when I switched web hosts and blogging platform. Over the weekend, I resurrected it from the backup and turned it into a good old static website with a home page at http://www.leancrew.com/mechanics/.

Mechanics is an undergraduate textbook in statics and dynamics, pitched primarily at sophomores and juniors in mechanical and civil engineering. It was a fairly popular book in its day, which was 60 years ago, but I don’t think it’s being used as a classroom text any more. It does, however, have a wonderful set of problems, and because it’s a Dover reprint, it’s quite inexpensive. If I’m more diligent this time around, the finished web site will be a good resource for engineering students—they’ll be able to see how an expert solves these types of problems without being given direct answers to problems in the texts they’re using in class.

Expert? Yes. The stuff I tend to do on this blog (with one or two exceptions) is hobby stuff, not what I do professionally. I got my Ph.D. in civil engineering from the top-ranked civil department in the US and later taught mechanical engineering—including statics and dynamic—at a fairly well known university just north of Chicago. One of the things I miss most from my teaching days is working out the solutions to problems like those in Mechanics.

So why did the blog peter out in the first place? I ran into two roadblocks.

The first roadblock was pedagogical. When I hit Chapter 4, which starts off with truss problems, I had trouble deciding how to approach the problems. There are two methods of solving truss problems by hand: the method of joints and the method of sections. Den Hartog, like most authors, assigns some problems to be done by one method and some to be done by the other. My first inclination was to simply do the problems using the method he assigned, but I immediately had doubts. Some problems are best done by joints, some by sections, and some by a mixture of the two methods. Wouldn’t it be better to choose the more efficient technique and let the readers in on why I made the choice? As I held up posting until making this decision, I realized that another roadblock awaited.

The second roadblock was practical. Solving a truss problem usually means making several drawings of different parts of the truss. This goes pretty quickly when you’re making the drawings by hand, but I didn’t want scans of hand-drawn figures. I wanted crisp, clean, computer-generated figures, like I’d drawn for the earlier problems. I’d drawn the earlier figures in Illustrator and exported them as PNGs; I was happy with their quality, but not so happy with the speed at which I produced them. The prospect of needing four or more figures per problem instead of just one or two stopped me cold.

Now I think I’ve got a way around both roadblocks. I’ve decided to do the problems the way I think is best, regardless of how Den Hartog assigned them. I’m pretty sure I’ll be repeating this decision when I get to rigid body kinematics later in the book; Den Hartog doesn’t use vector notation because it wasn’t the style back then, but I definitely will.

As for the drawing roadblock, I now have a copy of OmniGraffle, and ever since I bought it I’ve been thinking that it’s ability to link elements together is perfect for drawing trusses quickly and accurately. I’ll soon learn if I was right.

Switching to topics more common on this blog: The soutions are written in a customized Markdown format that includes LaTeX-style equations via jsMath. The HTML pages are generated by a few Python scripts and a couple of Makefiles. The overall approach was adapted from my no-sever personal wiki (described here, here, and here), and I’ll probably write a couple of posts on how the Mechanics pages are made after I’ve been in production for a while and have worked out the kinks. I’m using Git to keep both the solutions and the page-generating scripts under version control; one of the scripts creates an RSS feed from the commit messages for the solutions.

As it stands, there are currently 80 solved problems from Chapters 1–3. I’ll start adding to it this weekend.