An iTunes U recommendation

August 13, 2009 at 8:44 AM by Dr. Drang

I’ve been listening to David Blight’s wonderful series of lectures on The Civil War and Reconstruction Era, 1845-1877, one of the Open Yale courses available through iTunes U. It’s 27 lectures, each about 50 minutes long, taken from the Spring 2008 session of Yale’s History 119 course. The short course description:

This course explores the causes, course, and consequences of the American Civil War, from the 1840s to 1877. The primary goal of the course is to understand the multiple meanings of a transforming event in American history. Those meanings may be defined in many ways: national, sectional, racial, constitutional, individual, social, intellectual, or moral. Four broad themes are closely examined: the crisis of union and disunion in an expanding republic; slavery, race, and emancipation as national problem, personal experience, and social process; the experience of modern, total war for individuals and society; and the political and social challenges of Reconstruction.

There are two versions of the course, audio and video. Because I wanted to listen while driving and biking, I downloaded the audio version. I suppose it might be nice to see a map once in a while, but I really haven’t felt as though I’m missing much by not having pictures.

Before discussing the course, I should mention its dangers. The Civil War is a topic that attracts buffs, especially among middle-aged white men, the demographic I happen to inhabit. As I was looking through the Open Yale offerings, I skipped over History 119 a couple of times. I was afraid that listening to it would identify me as a buff. Worse yet, it might turn me into one. Don’t get me wrong, buffs can be very nice guys1—a bit boring, perhaps, but relatively harmless. Among the foolish things men do in middle age, becoming a Civil War buff ranks as somewhat more foolish than becoming an avid biker (ahem) but less foolish than chasing after young women and—worst of all—golf.

The big danger of Civil War buffness is that it’s a gateway to becoming an re-enactor. One day you’re making room on the shelf for your Ken Burns DVD set and thinking about swinging through Chickamauga on the next family vacation; the next you’re growing out your mutton chops and wearing a woolen union suit in a canvas tent while having a heated discussion over the relative merits of James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson.

Truthfully, History 119 isn’t likely to be especially thrilling to buffs. Only about a third of the course covers the war itself, and even that part doesn’t get into tactical details. Blight is more interested in telling us what America was like and how it changed—and didn’t change—over the course of those three middle decades of the 19th century.

I was at first put off by Blight’s voice; it seemed like he was doing a bad Garrison Keillor impression. But the strength of the material and the way he constructs his lectures soon won me over. Like every class I’ve attended—or taught, for that matter—History 119 has digressions, but Blight sticks pretty faithfully to the narrative he’s built.

With about two-thirds of the course behind me2, a few things stand out:

- Blight enjoys discussing the mechanics of history—how the study of history is done by those who do it—and how interpretations change with the times and are strongly influenced by the times. As an example, after the senseless and avoidable First World War, there was a school of thought that the Civil War could have been avoided. That interpretation died out among historians who lived through World War II. The importance of interpretation to the study of history isn’t surprising to me, but it’s very different from the math, science, and engineering courses that filled my college years. In those courses, there is no interpretation to speak of; knowledge accumulates, and what we know now is always more and better than what we knew in the past. It’s interesting to see how others approach their field of study, and it’s clear that—in addition to providing general education—Blight is training historians.

- The importance of South Carolina in the Confederacy. When I think of South Carolina at all, it’s usually during the Republican presidential primary, when the controversy over the Confederate flag awakens after a four-year sleep. Seeing South Carolina as the home of John C. Calhoun, the first state to secede, and the site of Fort Sumter clarifies its obstinance over the flag.

- The political arguments made by the white South have, in their fundamentals, changed very little in 150 years. The biggest difference is that today the Republican party is making those arguments rather than repudiating them.

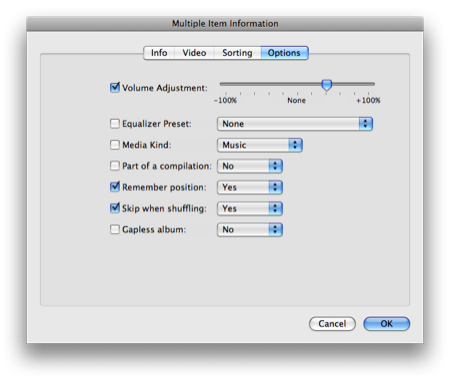

A few technical notes on the recordings. While the sound quality is good, with little of the echo common to recordings in lecture halls, it is at a fairly low volume. Also, the tracks are not excluded from shuffle play and do not remember their position—settings which are inexplicable for tracks of this type and length. All three of these problems are easily fixed by selecting all the lectures, invoking the iTunes Get Info command (⌘-I), and changing the settings like this