I'll wait, my dear, till it's my turn

September 3, 2015 at 12:21 AM by Dr. Drang

I know there are more good podcasts than there is time available to listen to them, but you really should give Stephen Hackett and Jason Snell’s new Liftoff podcast a try. It’s fun and informative without being overly technical. Unlike certain blogs I could name.

In the current episode, Stephen and Jason talked about the Moon, and it got me thinking about tides and gravitational forces. After my recent calculation of the position of the L1 Lagrange point, I was confident I could do something similar with tidal calculations. Nope.

Oh, there are lots of explanations of tides, both online and in books, but the overwhelming majority of them are qualitative, somewhat handwavy when it comes to the hard parts, and often flatly wrong. The page Stephen and Jason linked to in their show notes, for example, has some pretty silly stuff in its “Facts” section. I like this page from NASA, but it’s explanation of why the Moon produces a tidal bulge on both the near side and the far side of the Earth is just gibberish.

Why do I like a page with gibberish? Because it also has these two animated GIFs, which do a great job of showing how the tidal bulges move across the Earth’s surface. The first one shows just the rotation of the Earth,

Animation from NASA.

and the second one shows the combined effect of the Earth’s rotation and the Moon’s revolution.

Animation from NASA.

But what causes the water to bulge? The best simple explanation I’ve seen was given by Isaac Asimov. Unfortunately, I can’t remember which of his books it was in, but the explanation itself has stayed with me since I read it as a teenager. It’s because the gravitational force from the Moon is not constant over the entire Earth’s surface.

The total gravitational force from the Moon on the Earth comes from Newton:

where is the mass of the Earth, is the mass of the Moon, is the distance between their mass centers, and is the universal gravitational constant.1 The average force per unit mass (of Earth), which we’ll call , is obtained by dividing the total force by the mass of the Earth:

But because not every point on (and in) the Earth is a distance away from the Moon’s center of mass, the local value of the force per unit mass, , varies. In particular, directly below the Moon, the value of is

where is the radius of the Earth. This is about 3% higher than . Similarly the value of at the point directly opposite the Moon is

which is about 3% less than . The elliptical elongation, the bulging, comes because the water nearest the Moon is pulled the most, the water farthest from the Moon is pulled the least, and the water in between is pulled by an amount in between.

If you want a more in-depth accounting of tides, and you’re not afraid of a little multivariate calculus, take a look at Robert Stewart’s explanation. Stewart is a professor of oceanography at Texas A&M, and he doesn’t do any handwaving. Unfortunately, there are some errors in the equations on Stewart’s web page that seem to have come about through a LaTeX-to-HTML conversion. If you want to follow along with his derivations, you’re better off downloading the PDF of his book and flipping to Section 17.4. I found no errors in the PDF.

I won’t replicate his derivations here. For our purposes, the key result is that the gravitational force per unit mass of Earth due to the Moon can be broken into two parts:

- A part that’s constant in magnitude throughout the Earth and is directed parallel to the line connecting the two mass centers. This can be thought of as the part associated with the centripetal acceleration of the Earth’s orbit around the Earth-Moon barycenter.

- A part that varies in magnitude and direction from point to point on the Earth. It is the horizontal component (that is, the component tangent to the surface of the Earth) of this part of the gravitational force that pulls the water into the tidal bulges.

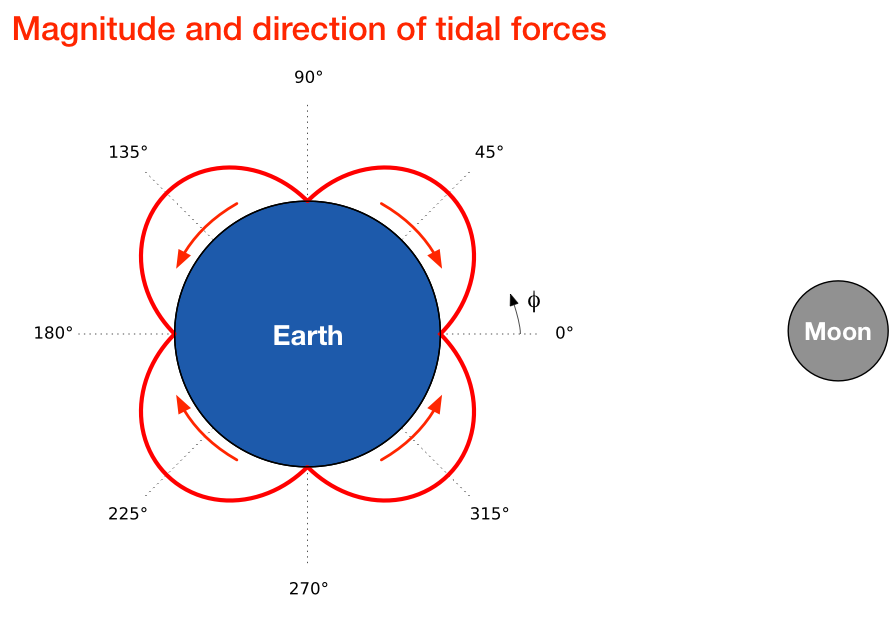

The horizontal tidal force per unit mass, which we’ll call , is governed by this formula:

where is the angle from the point directly under the Moon, as shown in the figure below, and is the unit vector in the direction. We can account for both the magnitude and the direction of this force by plotting it around the circumference of the Earth:

The red lobes show the magnitude, which is zero when is 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270° and at its maximum when is at 45°, 135°, 225°, and 315°.

The red arrows show the direction of the horizontal tidal force, and here’s where we see why there are bulges on both sides. The water on the half of the Earth closest to the Moon is being driven toward the point directly below the Moon. The water on the half of the Earth farthest from the Moon is being driven toward the point on the opposite side.

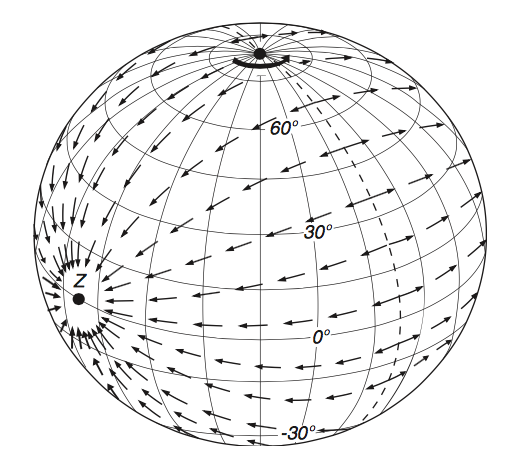

So far, we’ve only looked at 2-D views. Stewart has a nice 3-D view of the directions of the horizontal tidal forces when the Moon is over a point (Z) on the equator.

Source: Texas A&M University.

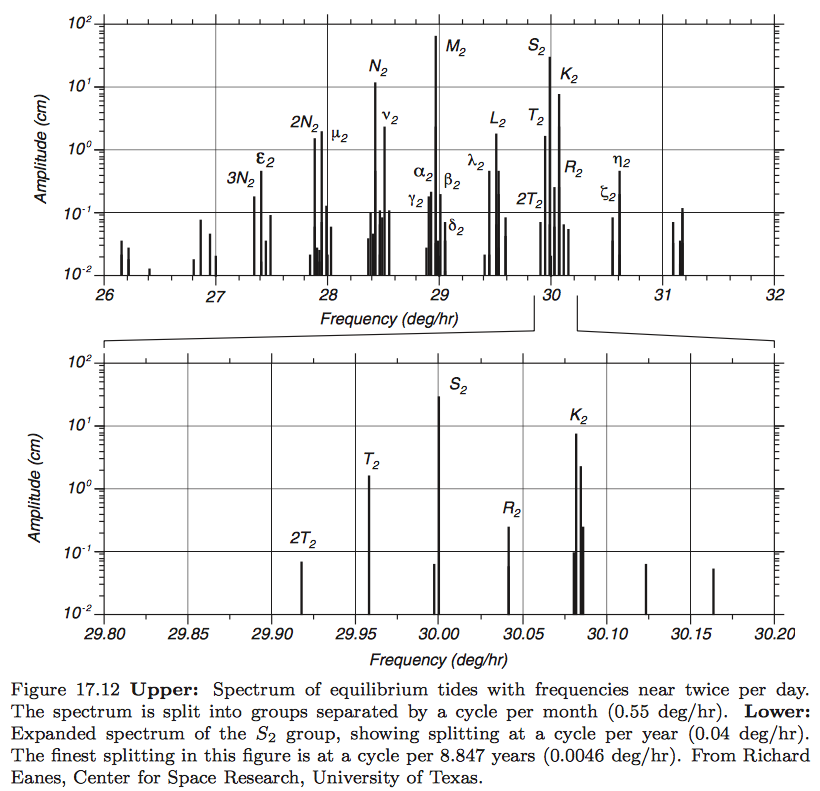

You can see things are getting complicated, and we haven’t even included the tidal effect of the Sun yet. Or the tilt of the Earth relative to the plane of the Moon’s orbit. Or the tilt of the Earth relative to the plane of its orbit. Or the eccentricities of the Earth’s and Moon’s orbits. Stewart puts all of this stuff together and shows that tides have a much richer frequency content than the simple “twice a day” explanation we usually see. Even in the neighborhood of “twice a day” (30° per hour) there’s a multitude of constituent frequencies.

Source: Texas A&M University.

If you don’t feel like following up on Professor Stewart’s calculations, you can always go with Debbie Harry’s explanation.

Hold on.

-

Which was first measured by Henry Cavendish in a famous and elegant experiment. ↩