Spike

June 30, 2013 at 9:38 PM by Dr. Drang

Journalists have recently fallen in love with the word spike used as a verb. This is about data analysis, not touchdown celebrations, beach volleyball, or a story being rejected by an editor. We now read that search warrants from the FISA court have spiked, peanut allergy diagnoses have spiked, the use of filibusters has spiked.

It’s interesting that this kind of chart-based terminology has made it into popular culture. It’s an indication that graphs, especially time-series graphs, have so insinuated themselves into our lives that reporters feel comfortable using what used to be a specialist’s term in articles for a general audience. Too bad they almost always use it wrong.

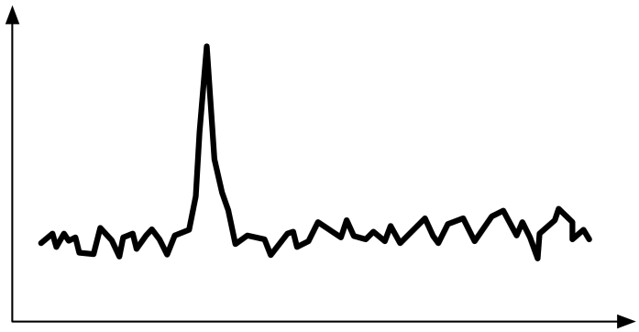

In a time-series chart, a spike is a brief period in which whatever is being tracked is much higher than usual. Your heart rate spikes during a life-threatening emergency, for example. If you have a water hammer problem in your plumbing, it’s because the pressure in the pipes spikes when you close a faucet. When graphed, a spike in the data looks like this:

Spike is a great word—short, punchy, and highly descriptive. Looking at the graph, it’s obvious where it comes from. It is interesting that sudden, brief downward drops aren’t called spikes—they look just as spiky and spikes are often pointed down. I guess it’s because we tend to think of the space below a line chart as solid and the space above as air. The terms peak and valley are other examples of this topographic interpretation.

Anyway, two things are necessary to make a spike: the jump in values must be significant and it must be of short duration. The first is, of course, a matter of interpretation. Is a 10% increase a spike? It could be if the usual variation is quite small, but whenever I read that something “spiked 10%,” I assume the reporter is being hyperbolic to make the story sound more important.

You could say that the brevity of a spike is also a matter of interpretation, but there’s one thing that’s indisputable: a rise in value isn’t a spike if it never comes back down. This is why the examples in the first paragraph aren’t spikes. FISA warrants are still high, as are peanut allergy diagnoses and Senate filibusters.

In mathematical terms, these things that reporters say are spiking are less like Dirac delta functions and more like Heaviside step functions. They aren’t spiking, they’re jumping.

Maybe I shouldn’t complain. If reporters weren’t saying these things are spiking, they’d probably be saying they’re at an inflection point, and the misuse of that term always causes my blood pressure to spike.