Day after day

January 2, 2016 at 11:55 PM by Dr. Drang

How many times does the Earth rotate in a year? If you’re a strong believer in the Gregorian calendar, you might say 365.2425 times, as that’s the average number of days in a year. If you know that the Gregorian calendar is a bit off, you might say 365.2422 times, as that’s closer to the average number of days in a solar year. If you don’t bother memorizing useless facts, you might say it’s about 365¼ times.

All of these answers are wrong. Or maybe they’re right. It depends on your point of view and how you define a single rotation. Overall, I’d say they’re more wrong than right, because to a remote observer, one whose view of the Earth isn’t skewed by being on it, the Earth goes through about 366¼ rotations for every trip around the Sun.

The key to this is the concept of sidereal time, which I first read about in some kiddy science book. The book did a such a bad job of explaining it, I decided it must be wrong. Some years later I read a better explanation by Isaac Asimov, but it was still confusing, mainly, I think, because there weren’t any illustrations to go along with the text. Also, despite its familiarity, the Earth is a poor example because its axis is tilted (and precesses), it doesn’t have a whole number of days in a year, and there are are just too many days in a year for easy visualization. I finally understood sidereal time after cutting out all the the complications and sketching the orbit of a simpler, imaginary planet.

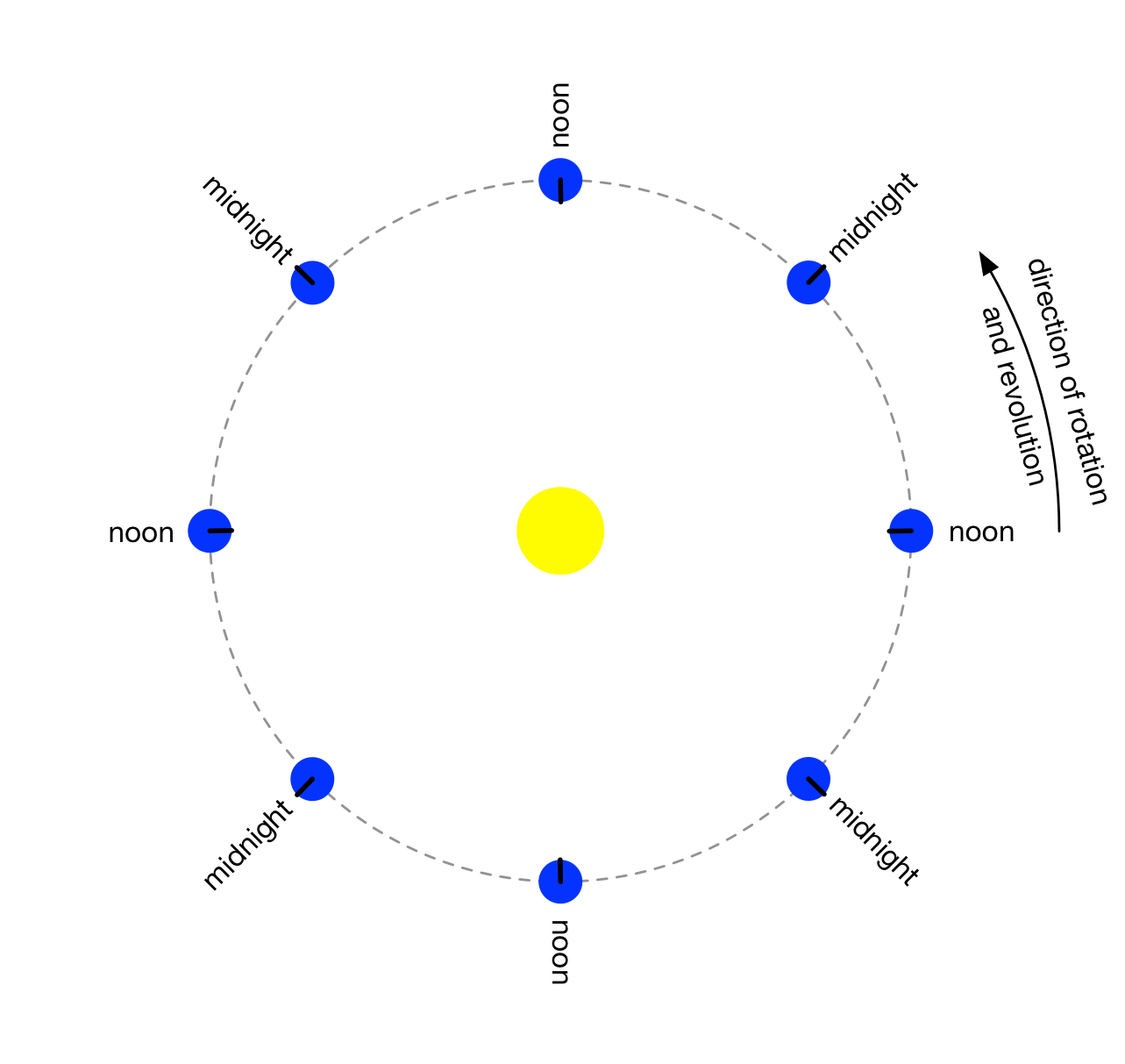

Here’s a really simple planet. It has a circular orbit, a four-day year, and its axis is perpendicular to its orbital plane. Like the Earth, it rotates in the same direction that it revolves. I’ve drawn a tick mark on the planet to make it easy to see its rotational orientation at different points in its orbit.

It’s probably a good idea to stop here and review our vocabulary. In astronomy, the word revolve refers to the motion of a planet about its sun (or a moon about its planet), while rotate refers to the spinning of a body about its own axis.1 To understand sidereal time, we have to see how revolution and rotation interact.

Imagine a person sitting on the tick mark, looking up at the sky. Noon for that person is when the tick mark points directly at the sun, and midnight is when the tick mark points directly away from the sun. The length of a day is the time between successive noons (or successive midnights). The four noons that occur during our planet’s year are 90° apart from one another on the orbital circle.

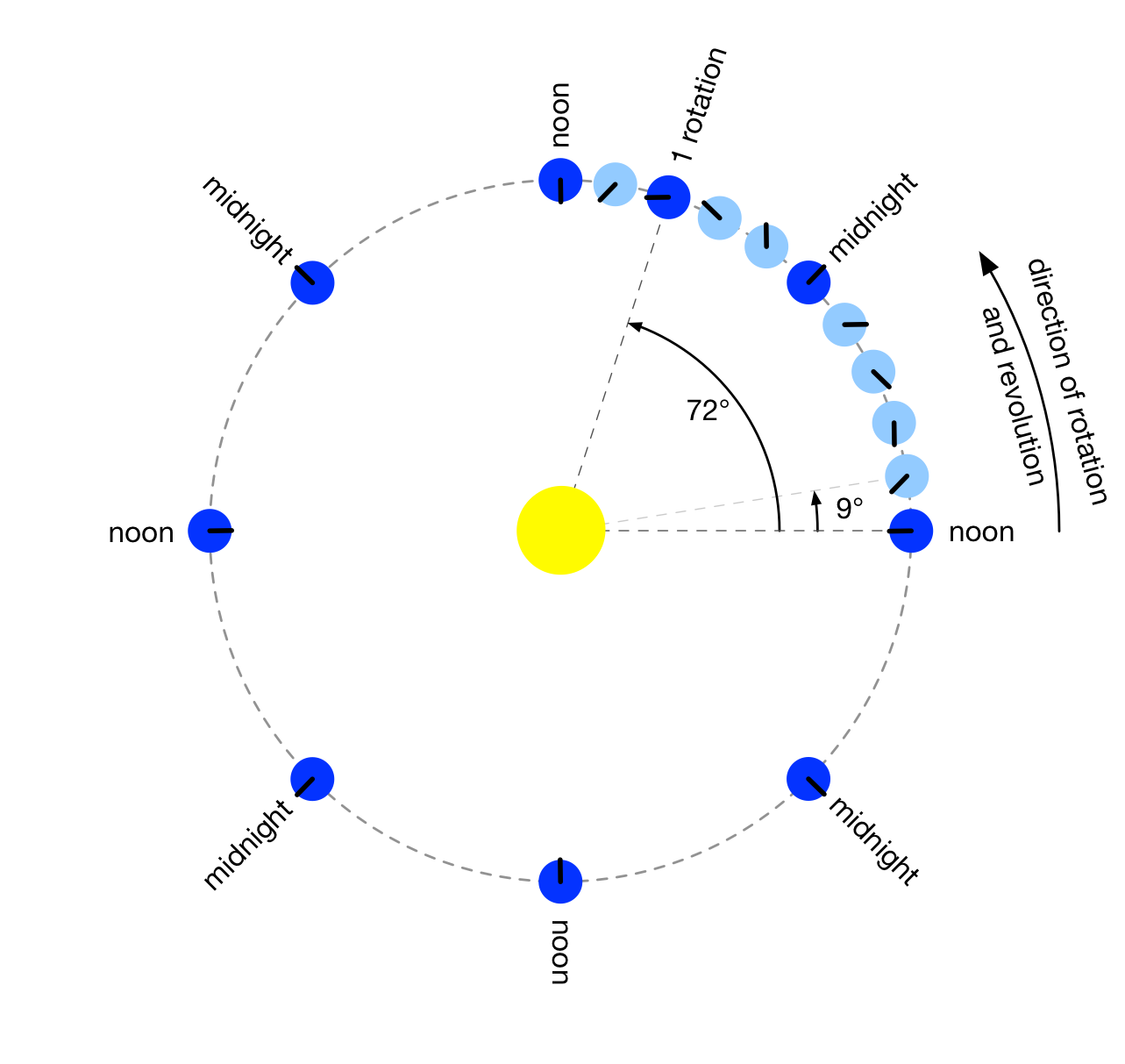

Now let’s look in more detail at a single day, the one in which our planet is in the upper right quadrant of its orbit.

From our position up here in space, we see that the planet rotates through 1¼ turns (360° + 90° = 450°) during this day. For every 9° of revolution, it rotates 45°. So from our godlike point of view, the planet goes through one rotation (360°) in eight-tenths of a day, or 72° of revolution. If the people on our imaginary planet measured their days in 24-hour increments, a sidereal day—the time it takes for one rotation as viewed from the godlike position—would be just 19.2 hours long.

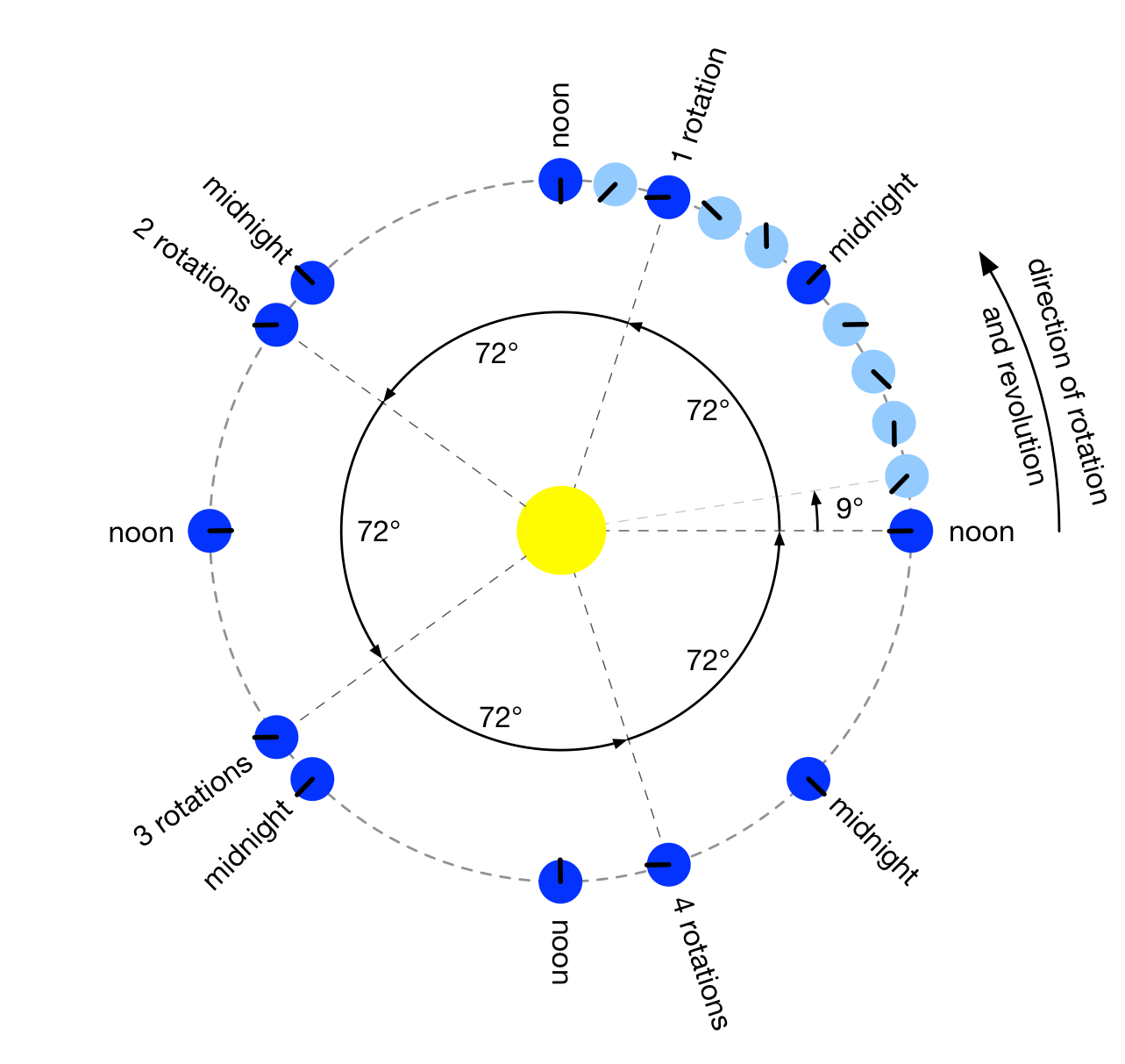

Now let’s add in some detail for the rest of the year.

Each 360° rotation of the planet comes with a further 72° of revolution about the sun. Therefore, while our planet has four days in a year, it goes through five rotations per year.

Now, our friend down on the planet may tell us we’re full of shit. Using the sun as his guide, he says his planet rotates four times in a year, not five. But he can say that only if he ignores the stars.

At midnight on the first day of the year, the stars he sees overhead are the ones off in the upper right quadrant. At midnight of the next day, a completely different set of stars are overhead, the ones off in the upper left quadrant. And that’s the clue that he hasn’t rotated 360° from midnight to midnight. That, in fact is where the word sidereal comes from; it’s from the Latin sidus, meaning star or constellation. A sideral day is one rotation relative to the fixed stars.2

In fact, if our friend on the planet thought about it carefully, he’d realize that the only way he knows that a year has passed is from looking at the stars. He doesn’t have seasons or changing amounts of daylight.

As it happens, you can do this same thought experiment with any length of year for your imaginary planet and you’ll find that the number of rotations, relative to the stars, is one more than the number of days, which go from noon to noon. Which is why I said at the beginning of the post that the Earth rotates about 366¼ times per year.

For a quick and reasonably accurate calculation of the length of the Earth’s sidereal day, we can divide the length of a year in days by the length of a year in rotations to get the fraction of a day it takes for one rotation:

This is about 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds. Clock drives on telescopes are set to turn at this rate to keep stars fixed in the field of view.

There are, as you might expect, some nasty bits I’m ignoring here, mainly having to do with precession and how we define an Earth year as being from one vernal equinox to the next, which isn’t exactly one full orbit. But then again, since we dick around with the meaning of sidereal to define the sidereal day with respect to the equinoxes instead of the fixed stars, it kind of washes out.

The inspiration for this post (but not the blame) can be credited to Jason Snell and Stephen Hackett. The most recent episode of their Liftoff podcast covered the Earth’s orbit, with side trips into solstices, equinoxes, and seasons. Their discussion of the year got me thinking of sidereal time. And the inspiration for the title was Badfinger.

Badfinger had several strong connections to the Beatles, which reminds me of another day-themed song.

The Beatles used a sidereal week.

-

When you study Newtonian mechanics and kinematics, you’ll learn that the distinction made between these two similar words is kind of artificial. What really matters are an object’s angular velocity and angular acceleration, which include both revolution and rotation. ↩

-

Yeah, fine, the stars aren’t really fixed. But they look fixed compared to the Earth, the Sun, and all the other stuff in the solar system (and in our imaginary solar system). ↩