A sense of structure

November 30, 2025 at 10:45 AM by Dr. Drang

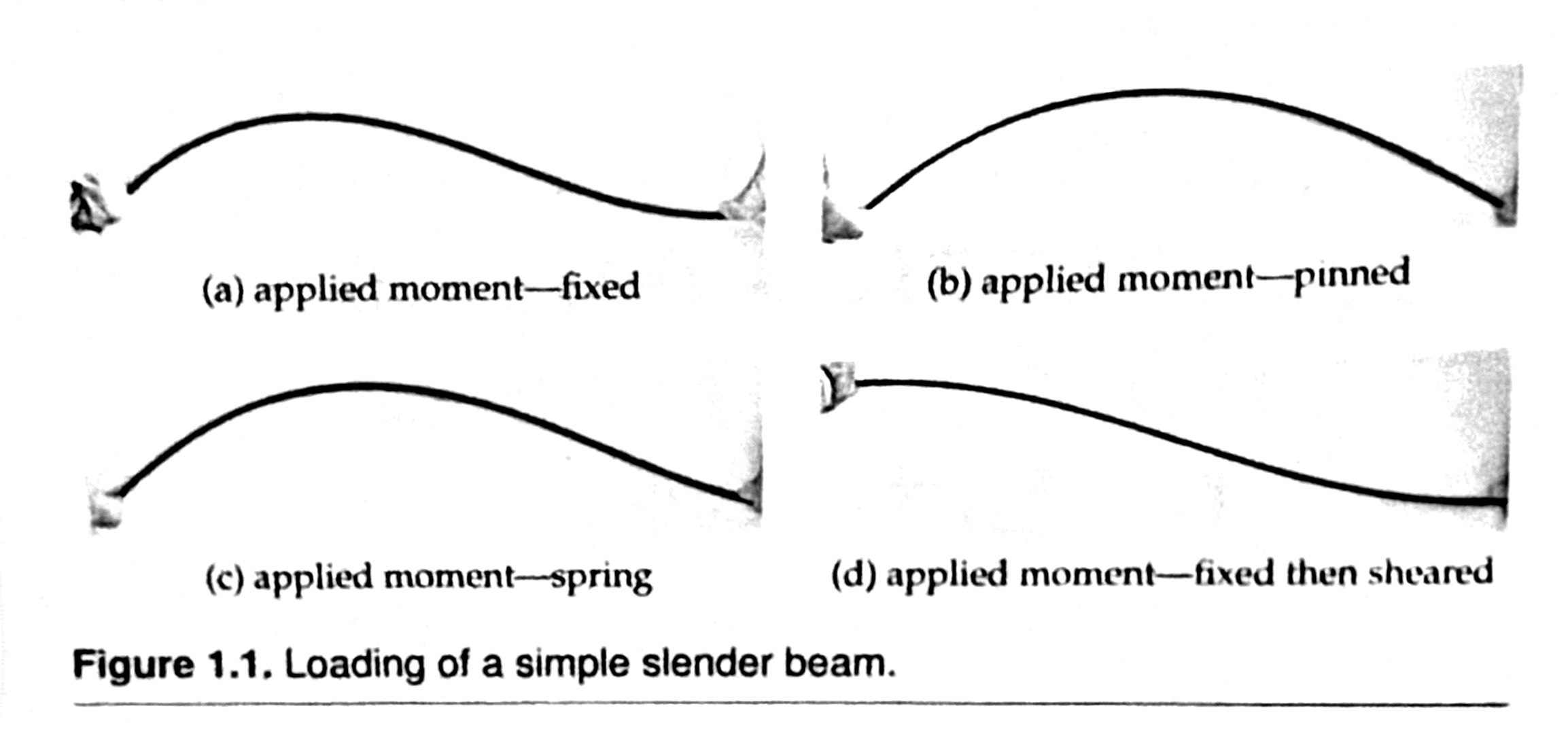

I checked out Practical Approximate Analysis of Beams and Frames from the University of Illinois library a couple of weeks ago. I haven’t dug into it deeply yet, but I smiled in recognition of some of the early material. Here, for example, are some poorly reproduced photos of beams being bent by end loads and moments:

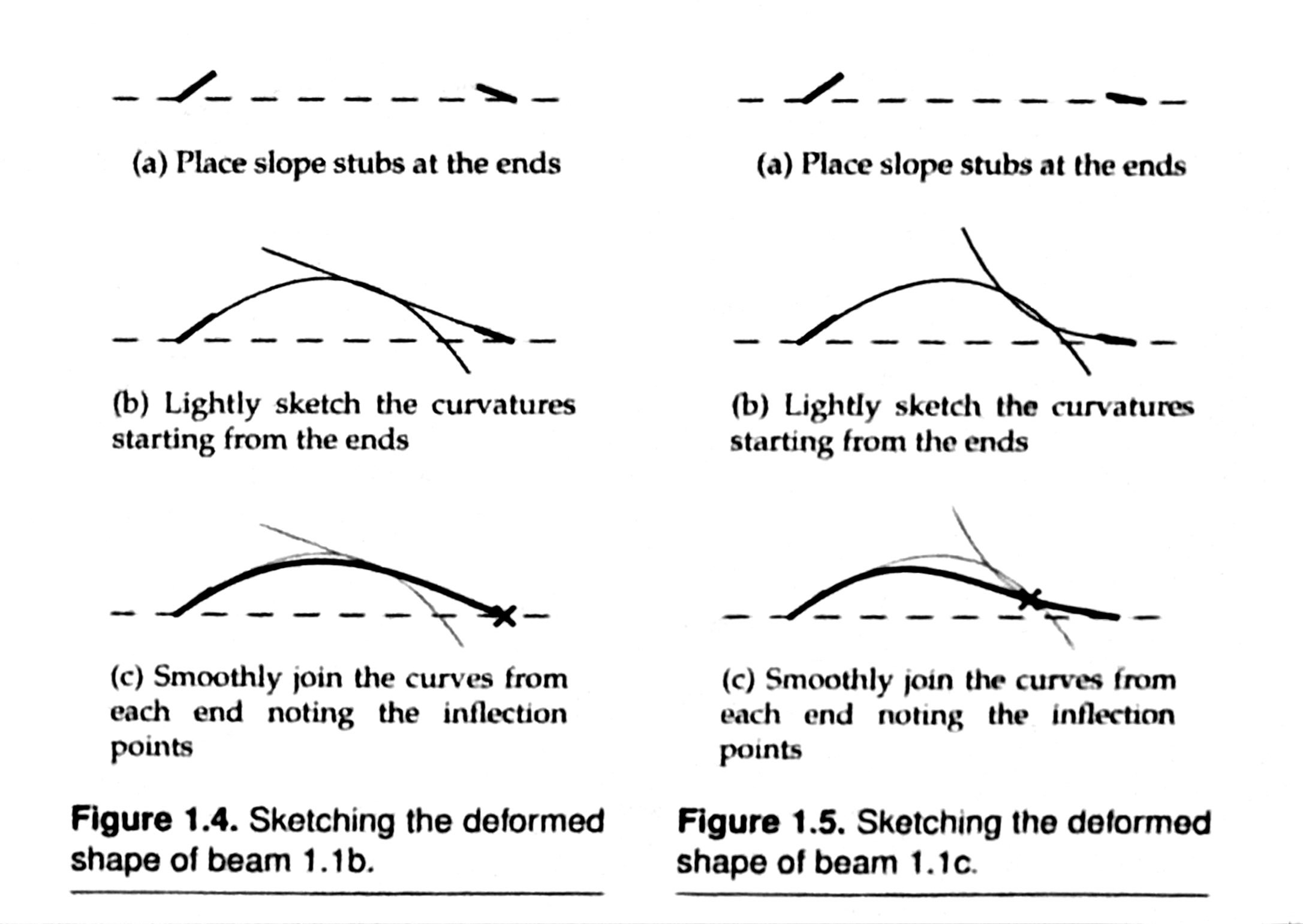

The author uses these photos to explain how the analyst can sketch reasonable approximations to the bent shapes.

The inflection point mentioned in the (c) subfigure of Figures 1.4 and 1.5 is the point at which the curvature changes from concave down to concave up (or vice versa). This is helpful in analysis because it tells you where the internal bending moment in the beam is zero. Internal bending moments are what determine the important stresses in a beam.

All of my structural engineering professors emphasized the ability to sketch reasonably accurate deflected shapes of the structures we were analyzing, even though we were doing exact1 analysis, not approximate analysis. None were more adamant about this than John D. Haltiwanger, who told us at the beginning of the semester that he would take points off of our homework if it wasn’t accompanied by a good sketch. We all learned that this was not an idle threat and that Prof. Haltiwanger’s standard for “good sketch” was higher than ours. He was my favorite professor as an undergrad.

A few years later, my ability to quickly and accurately sketch the deformed shape of a structure came up during a “pre-prelim” exam. It’s common for Ph.D. candidates to go through a preliminary (or qualifying) exam before moving from the coursework portion to the research portion of their graduate school years. This is essentially a presentation of the proposed research to a small committee of faculty. In theory, the questions asked during a prelim can cover not only the proposed work but any topic in which the candidate had taken a class. The committee members are typically the professors who had taught those classes. Prelims are part of a long tradition of doctoral programs weeding out undesirables.

The Civil Engineering Department at U of I had adopted a further tradition of “pre-prelims.” Before the prelim, the candidate would schedule an hour or so with each member of their committee who would give a short oral exam on the topics covered in class. This made the prelim itself more streamlined, but it also meant that the pre-prelims could be pretty detailed.

My pre-prelim with Arthur Robinson had the following question:

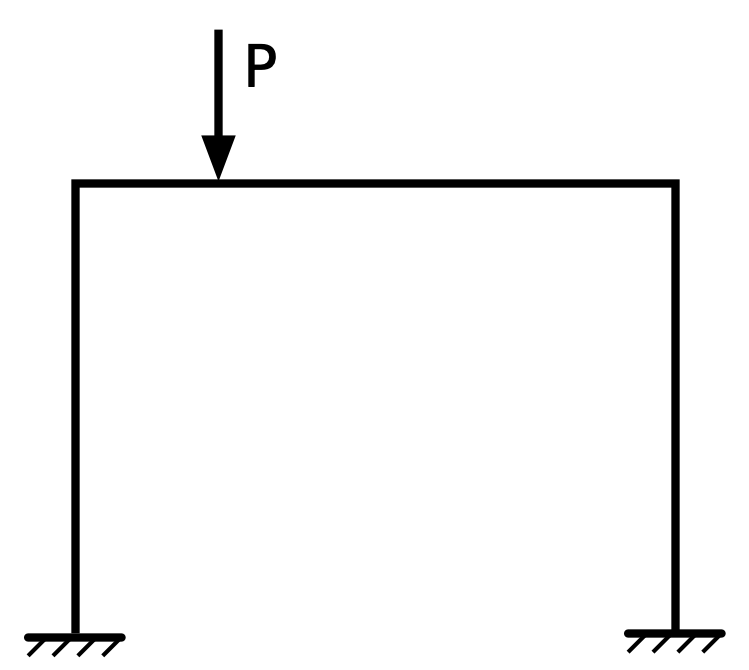

You have a single-story, single-bay 2D frame in which the columns are identical and the beam is prismatic. If a concentrated downward load is placed on the beam to the left of the centerline, which way does the frame sway? Don’t do any calculations, just reason it out.

Let me start by explaining the problem and giving a little background on what everyone in my position would be expected to know. Here’s what the structure and load look like:

And here are the assumptions we start with:

- Because both the structure and the load are in the plane of the screen, the deformations will also be in that plane. While real structures are always three-dimensional, and most have more than one (vertical) story or (horizontal) bay, this simple structure has many features of more complex structures and is a good pedagogical tool.

- The connections between the beam and the columns are rigid, which means they maintain their 90° angles during the deflection. The connections at the bottoms of the columns can be pinned (free to rotate) or fixed (unable to rotate). The direction of sidesway doesn’t depend on those connections, so I’ll assume they’re fixed. That way I don’t have to draw little hinges at the column bases.

- A prismatic beam is one whose cross-section is constant along its length. A prismatic beam and identical columns makes the frame symmetric about its centerline. If the concentrated load were applied to the center of the beam, the symmetry of the structure and load would lead to symmetric deformation and, therefore, no sidesway. The off-center load is the reason there must be sidesway.

There are at least a couple of ways to solve this problem. One would be to start by considering the directions and relative magnitudes of the bending moments at either end of the beam and work out how those moments affect the deflections of the columns. But this is a grubby sort of solution, and I knew Prof. Robinson wanted something more elegant.

The key is a principle that goes by several names: Maxwell’s Principle, Betti’s Law, and the Reciprocal Relationship are fairly common names, but almost any phrase that includes some combination of Maxwell, Betti, Reciprocal, Law, Relationship, Principle, or Rule will work. The Maxwell is James Clerk Maxwell, the great Scottish physicist known for his much more famous work in electromagnetism. The Betti is Enrico Betti, an Italian mathematician not particularly well known at all.

As a young man, I assumed that the principle in question was discovered first by Betti and independently rediscovered by Maxwell. In my head canon, Maxwell’s name was assigned to it by the English-speaking world in a spasm of Anglocentrism. But that’s wrong. Maxwell got there first with a limited version of the principle that Betti extended and generalized several years later.

Here’s the gist of the principle: We have a structure that is acted upon at different times by two sets of applied loads, called A and B. Each of these sets of loads will generate a deformation in the structure, which we’ll also call A and B. The Maxwell-Betti Reciprocal Principle2 is:

The work done by the A loads acting through the B deformations is equal to the work done by the B loads acting through the A deformations.

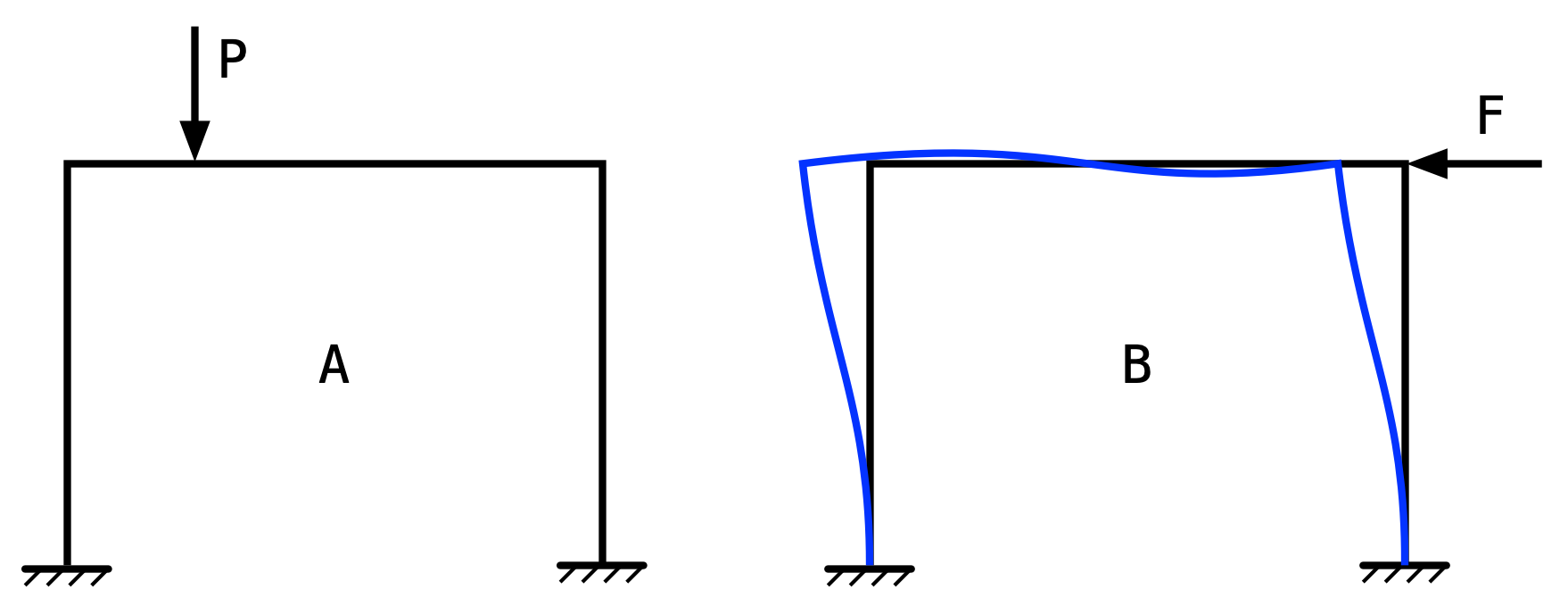

To apply this to the problem at hand, we take the original problem statement as A and create a new load and deformation B.

I chose System B to have a horizontal leftward load at the top of the frame, and because Prof. Haltiwanger had pushed me to quickly and accurately draw so many structural deformations, I knew it would deflect into the shape given by the curved blue lines without any calculations.

Reciprocity says that the work done by Load P acting through the deformation of its point of application in System B must be equal to the work done by Load F acting through the sway in System A. Since the left half of the beam in System B deflects up and Load P is down, that work is negative. For the work of Load F acting through the sway of System A to be negative, System A must sway to the right.

Obviously, it didn’t take me this long to explain my solution to Prof. Robinson. He knew where I was going with it as soon as I drew System B on the blackboard. We moved on to his next problem, which I think had to do with the vibrational mode shapes of a system of three masses and springs arranged in a triangle.

(A small confession: grad students talk to each other. Everyone in the department knew that this was one of Prof. Robinson’s favorite problems, so I was prepared for it. I knew the solution on my own, but I certainly wouldn’t have done it as smoothly without the heads-up.)

I don’t remember Prof. Robinson putting any emphasis on drawing deformed shapes in the classes I took from him. He just expected us to be able to do it and to understand the consequences of the shapes we drew. Like in his pre-prelim problem.