Axial vs. bending stiffness

December 19, 2025 at 12:02 PM by Dr. Drang

At the end of yesterday’s post, I mentioned that axial deformations in framework members are typically two orders of magnitude less than the lateral (bending) deformations. It’s easy to see why.

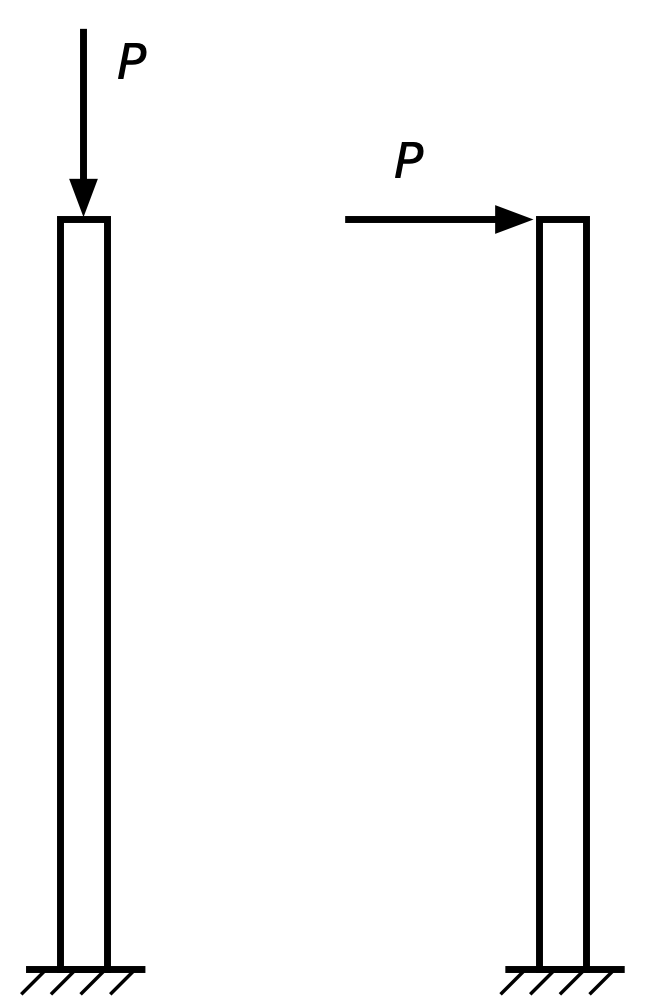

Consider a column with length , cross-sectional area , and moment of inertia . We’ll calculate the tip deflection of this column under two loads of the same magnitude, : an axial compression load and a horizontal load to the right.

Under the compression load, the tip of the column will move down by

Under the horizontal load, the tip will move to the right by

The ratio of lateral deflection to axial deflection is therefore

When calculating buckling loads of columns, it’s often useful to consider the radius of gyration, , which is defined this way:

We’re not doing a buckling calculation here, but we can use the radius of gyration to help us get a sense of the deflection ratio, which we can rewrite as

The radius of gyration is some fraction of a characteristic dimension of the cross-section. For example, if the cross-section is a square with side length , the area is and the moment of inertia is , so

In typical structures, the stick-like members—beams, columns, braces, etc.—tend to be long and thin, with aspect ratios of about 10. The deflection ratio is roughly the square of the aspect ratio, so lateral deflections are typically two orders of magnitude greater than axial deflections. That’s why it’s common to ignore the axial deflections in analyses like yesterday’s.

This doesn’t mean axial deflections can always be ignored. In tall buildings, the columns carry the weight of all the floors above them, and column shortening has to be accounted for, especially in the lower floors. Also, when using modern numerical techniques for structural analysis, there’s basically no extra work involved in calculating the axial deflections along with the bending deflections, so the axial deflections pop out of the computer as a matter of course.