Frame sidesway again

December 18, 2025 at 11:38 AM by Dr. Drang

I’ve been meaning to follow up on the “sense of structure” post I wrote just after Thanksgiving. I don’t have anything profound to say, but I did want to give complete solutions for both the off-center vertical load problem and the horizontal load problem.

First, though, I want to mention a nice email conversation I had with Karl Hoitsma, proprietor of the Mathpax blog. He pointed me to this post of his from a few years ago in which he describes being asked essentially the same frame sidesway question I was. The only real differences were that his oral exam was about five years after mine and that he was at Texas A&M instead of U of I. Oh, and he hadn’t been prepped for the question.

In that post, Karl gives a few solutions to the problem, which I found fun to go through. I had already solved the horizontal load problem for a simpler frame, and it was interesting to compare our approaches to the problem. As I’ve been trying to get better at Mathematica, I decided to do the off-center load problem and redo the horizontal load problem using the Wolfram Language. I won’t go through the code here, just the results.

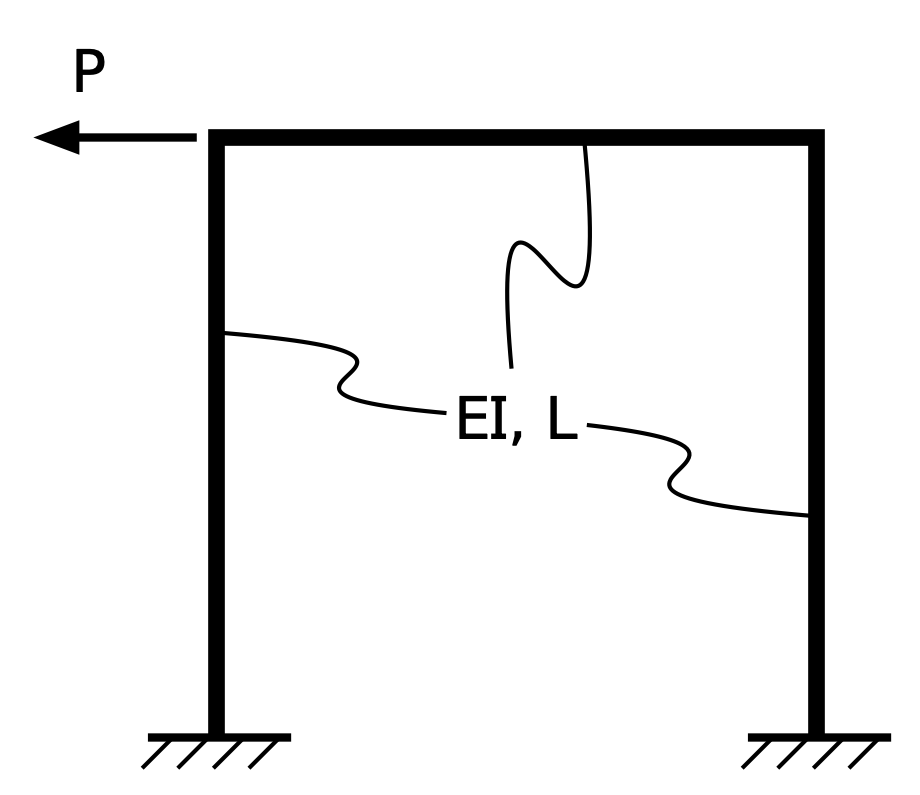

Let’s start with the simpler problem: a portal frame with fixed column bases in which the beam and columns are identical in both cross-section and length.

is the modulus of elasticity of the material, and is the moment of inertia of the cross-section.1

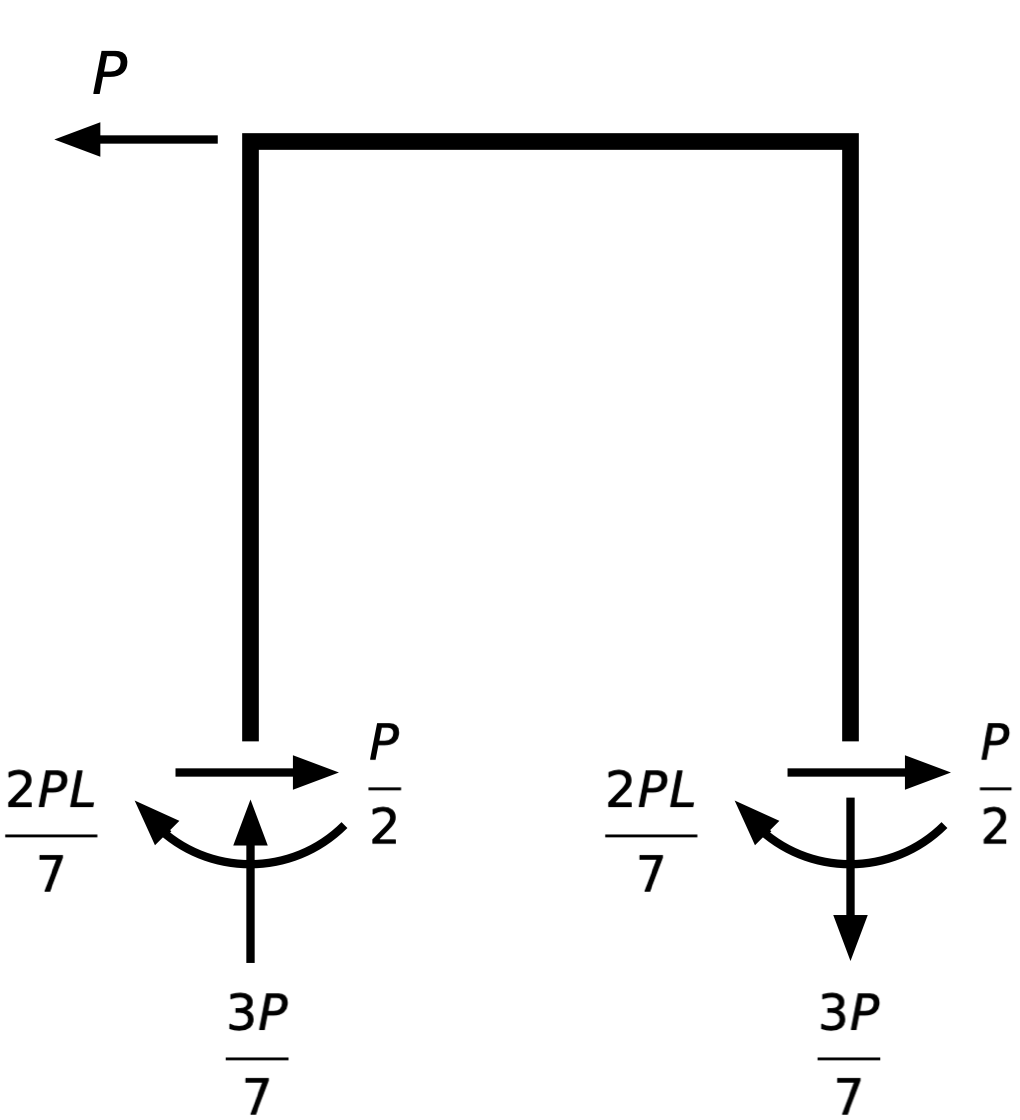

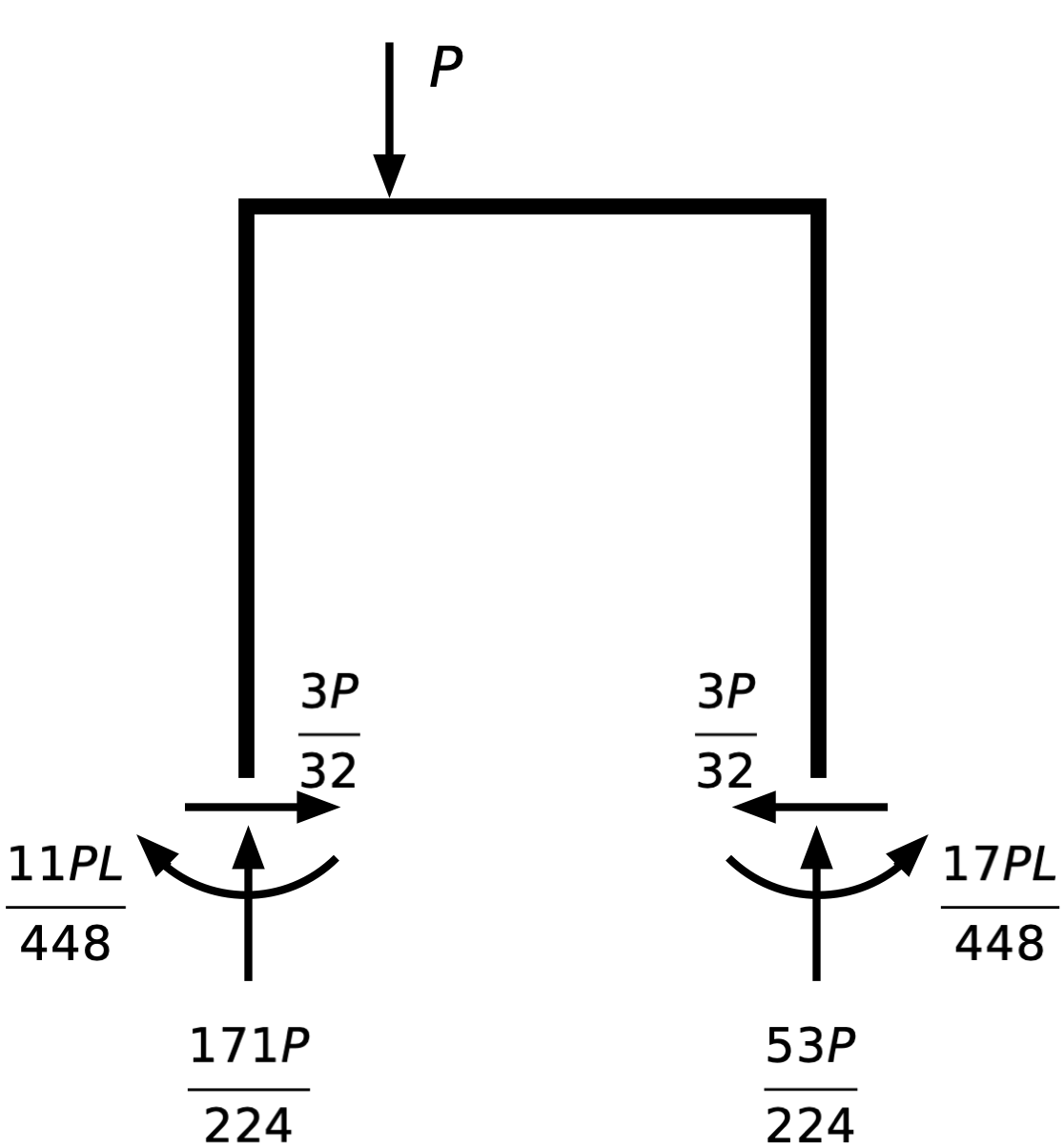

This is a statically indeterminate system. You cannot determine the reactions at the bases of the columns through statics alone; you have to account for the stiffnesses of the members. But once you’ve done that, the reactions are these:

It’s a decent exercise to confirm that these reactions are in equilibrium. It should be immediately obvious that the horizontal and vertical forces are in balance. It takes only a little more effort to show that the clockwise and counter-clockwise moments about any point are also in balance. (As a practical matter, I’d choose the base of one of the columns to take moments about, as that eliminates three of the forces from the equation.)

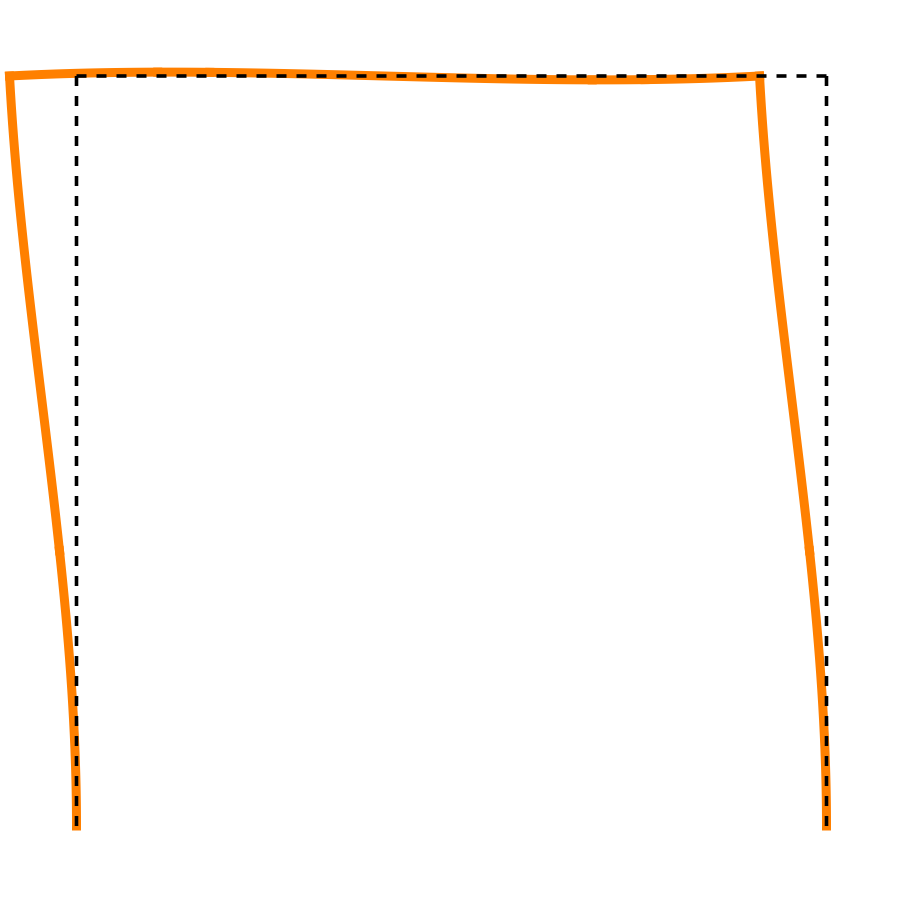

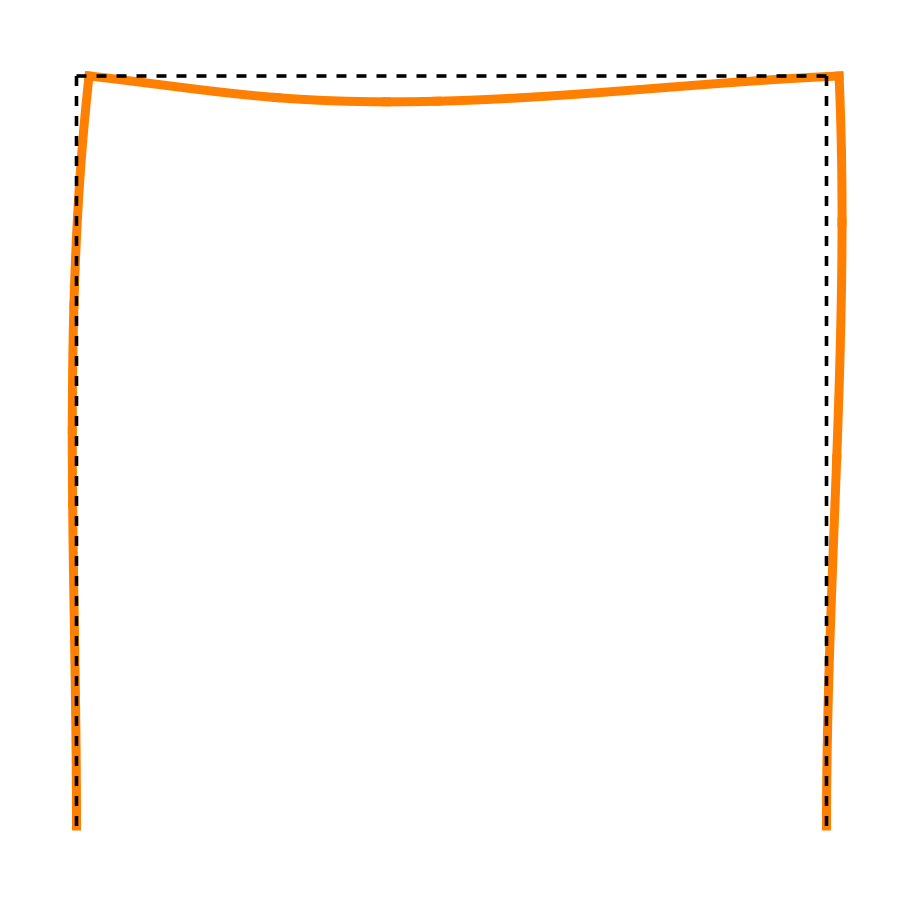

What I really wanted to show was the deflected shape of the frame under this loading. If you recall from that earlier post, I drew a deflected shape in which the left half of the beam goes up and the right half goes down. Knowing this was key to using reciprocity to determine which way the frame sways when it’s subjected to an off-center vertical load. Here’s the deflected shape plotted from a formal solution instead of just drawn on the basis of my sense of the structure’s behavior:

The leftward displacement at the top of each column is

and the counter-clockwise rotation at the top of each column is

It’s the CCW rotation that lifts the left half of the beam upward and pushes the right half downward. As you can see, though, the vertical deflection of the beam is pretty small compared to the horizontal deflection of the columns.

A note on units: In these equations, has units of force, has units of length, has units of force per length squared, and has units of length to the fourth power. So has units of length, as expected, and is a pure number, which means we’re getting the rotation in radians.

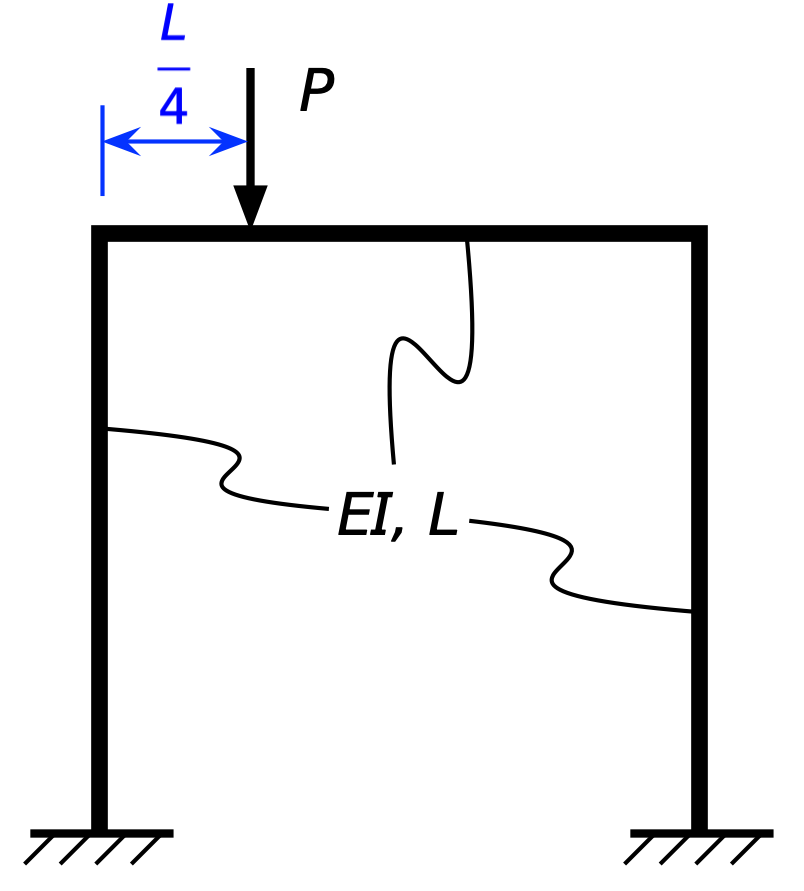

OK, now let’s look at the frame with a downward off-center load:

I’ve put the load at the quarter point of the beam for convenience, but it doesn’t matter where it is as long as it’s to the left of the centerline. Here are the reactions:

Again, you can confirm that these forces and moments are in equilibrium. Here’s the deflected shape:

For this loading, the leftward displacement at the top of each column is

The minus sign means the displacement is actually to the right, which matches what we figured out a few weeks ago. Now we have the magnitude in addition to the direction.

As I said above, I don’t want to go through the details of the code that got me to these answers, but if you’re interested, you can see it using the following Wolfram Cloud links:

I should mention that in both of these analyses I’m ignoring the axial deformation of the members. This is a common practice in frame analysis, as axial deformations are typically about two orders of magnitude less than lateral deformations. Leaving out the axial terms cuts out a lot of complexity in symbolic solutions like this while retaining good accuracy.

-

In physics class, you used a different moment of inertia when you were learning about rotating bodies. Strictly speaking, the in this problem should be called the second moment of area, but structural engineers always call it the moment of inertia. It’s a reasonable reuse of the phrase, as the second moment of area is a measure of the resistance of a cross-section to rotation as a structural member is bent. ↩