Overlapping rectangle puzzle

December 31, 2025 at 12:13 PM by Dr. Drang

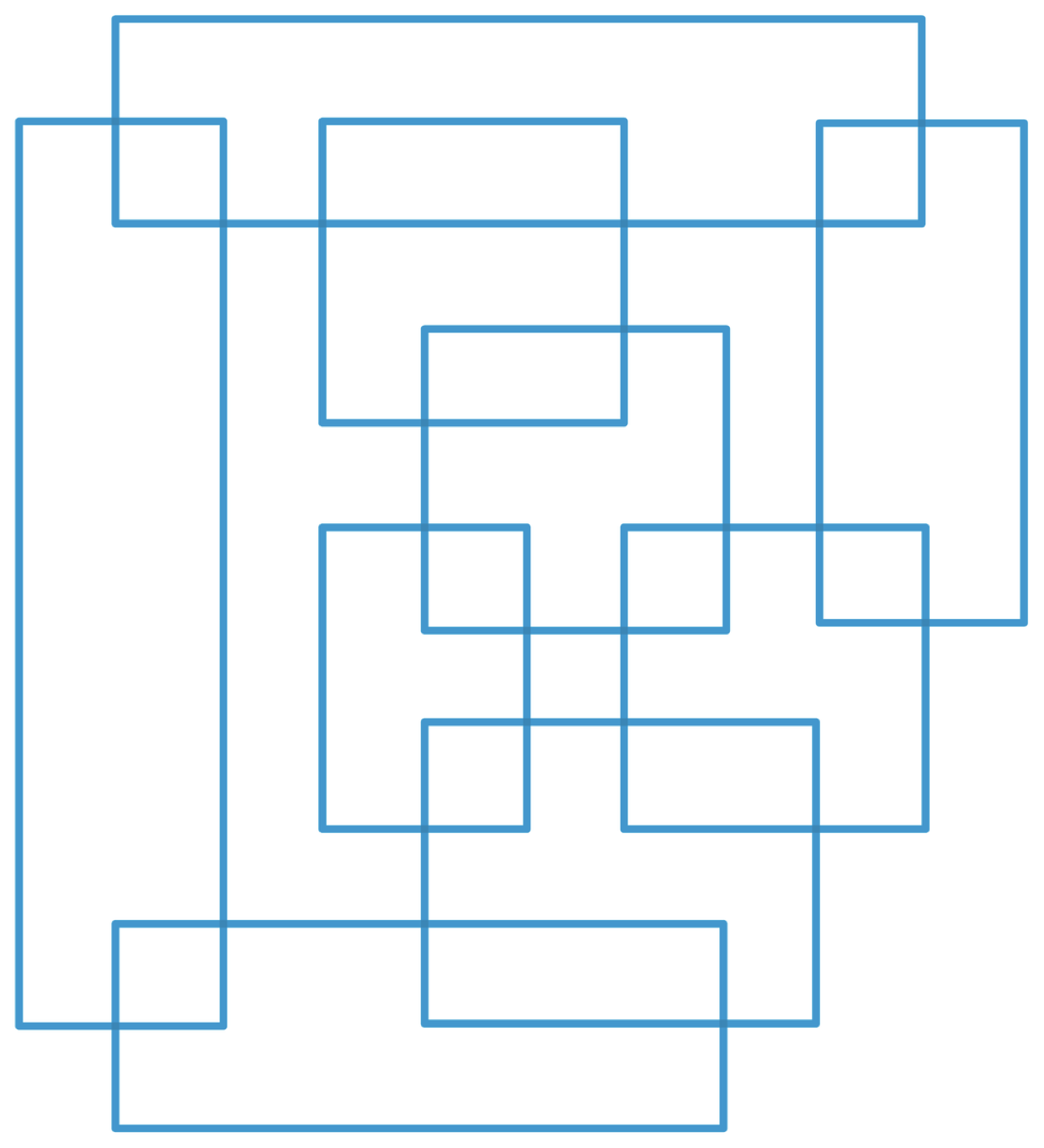

A couple of weeks ago, Scientific American published this puzzle.

There are nine overlapping rectangles, A through I. They overlap one another in a specific pattern using a notation I hadn’t seen before:

A\(D, F) F\(A, B, I)

B\(F, G) G\(B, C, I)

C\(G, H) H\(C, D, E)

D\(A, H) I\(E, F, G)

E\(H, I)

This means that rectangle A overlaps with two rectangles: D and F; rectangle F overlaps with three rectangles: A, B, and I; and so on. The goal is to correctly label the rectangles in the image.

My sense of the “right” way to handle this puzzle is to think of it as a network and use some powerful result from graph theory to solve it in an instant. But since the only thing I know about graph theory is that it exists, I went about it differently.

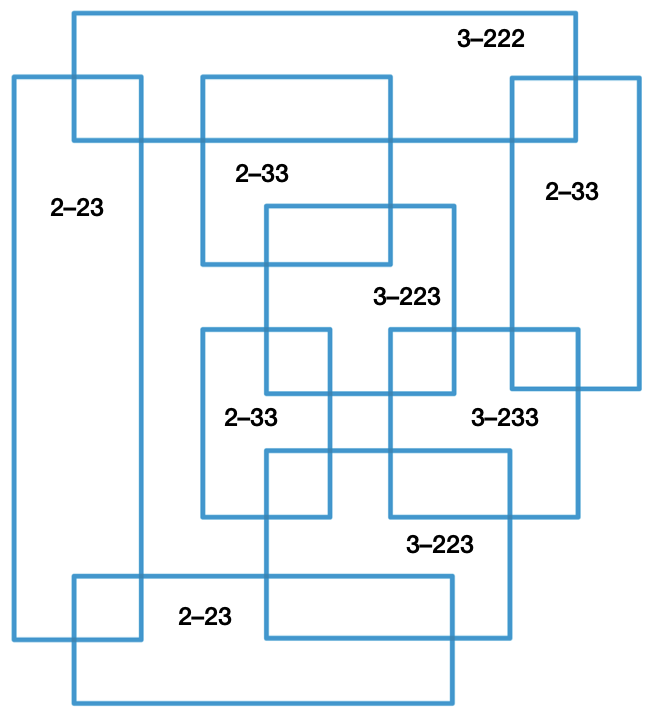

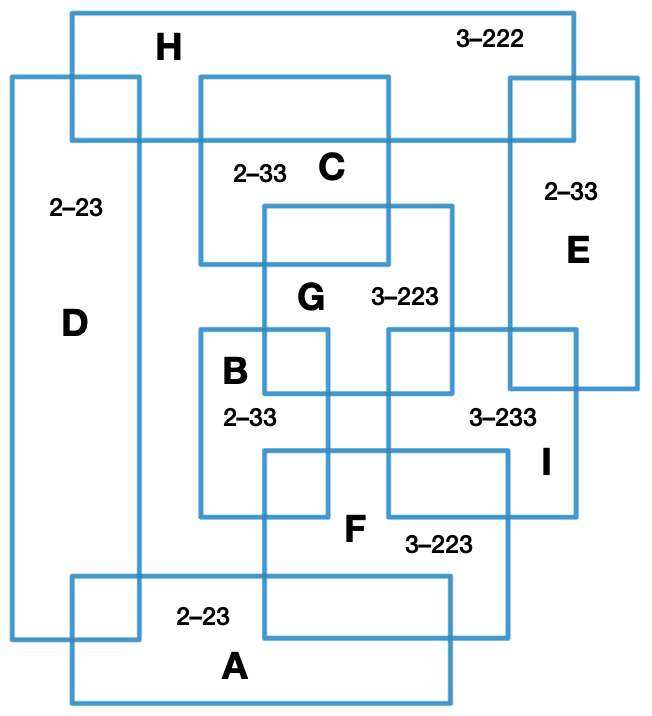

First, I labeled each rectangle with a code that indicates the number of rectangles it intersects and the number of rectangles its overlapping rectangles intersect.

For example, the rectangle at the top is labeled 3–222. That means it intersects three rectangles, and each of those intersecting rectangles intersects with two rectangles. I put the numbers after the dash in increasing order, just as the puzzle puts the rectangle letters in alphabetical order in its notation.

Then I added my notation after the puzzle’s notation:

A\(D, F) 2–23

B\(F, G) 2–33

C\(G, H) 2–33

D\(A, H) 2–23

E\(H, I) 2–33

F\(A, B, I) 3–223

G\(B, C, I) 3–223

H\(C, D, E) 3–222

I\(E, F, G) 3–233

The H and I rectangles are unique in my notation, so they could be identified immediately. I then went counterclockwise from H and saw that the leftmost rectangle had to be D (the only 2–23 intersecting H), the one at the bottom had to be A (the only 2–23 intersecting D), and then similarly up from the bottom through F, B, G, and C. E came from its connection to H and I.

When I looked at the SciAm solution, I was disappointed. It was faster than mine, but not because they used some clever math. They basically identified H and I using my method (albeit without my notation), figured out B and E from that, and then “the rest is simple.” It is simple, but it didn’t teach me anything new. Oh well, maybe next year.