Some lotto math

December 23, 2025 at 10:44 PM by Dr. Drang

I planned to talk about this post from Mathew Ingram, but things went in a different direction, and I learned something new.

The story is about a couple who recently won their second lottery prize of over £1 million. They won the EuroMillions Millionaire Maker back in 2018 and just won the UK National Lottery’s Lotto in November. According to the National Lottery operators, the odds of this are over 24 trillion to one. I was certain that this calculation had been done by multiplying the probabilities of each lottery win, and I meant to throw a little cold water on that.

First, that calculation would apply only if they played each lottery once, which I thought extremely unlikely. Also, it would apply only before their first win; after the first win, their odds of getting the second one are the same as anyone else’s.

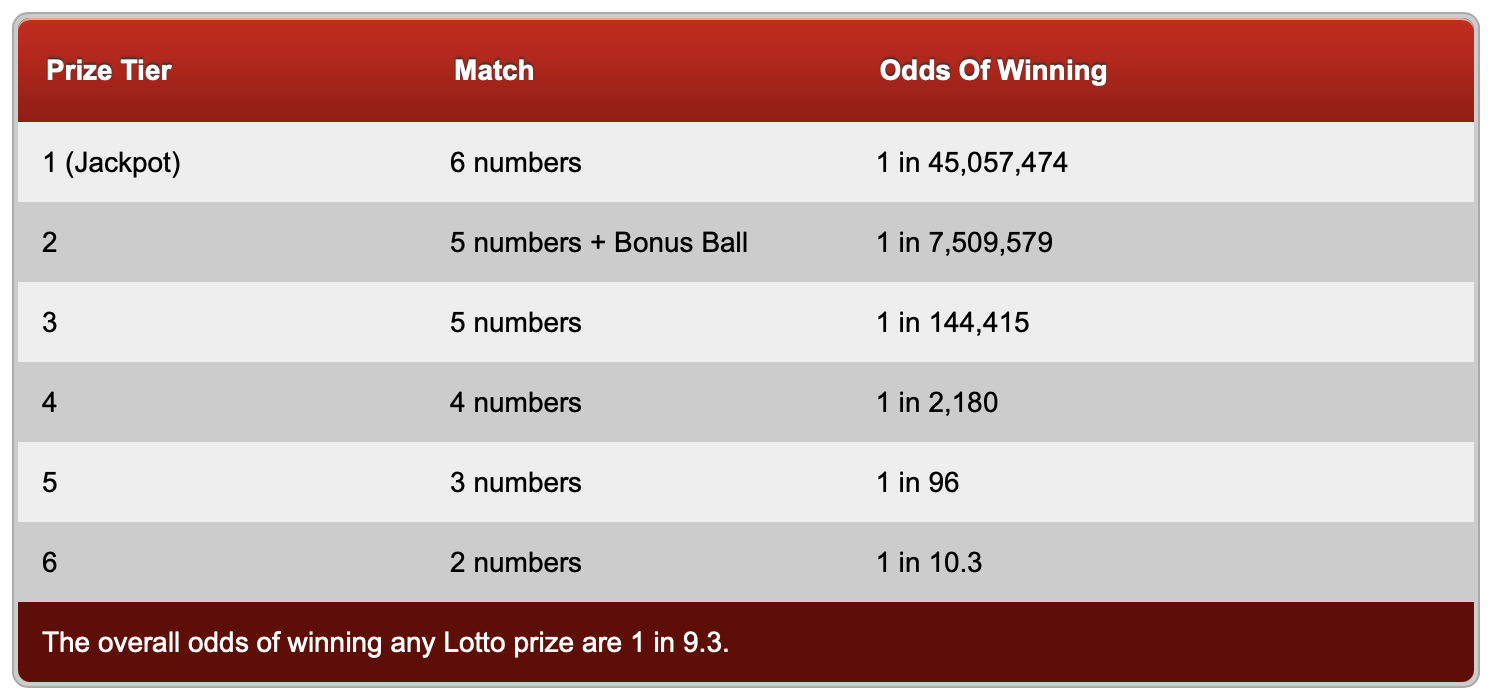

I wanted to include the odds of both games and show the calculation, but I was derailed. According to this page, the odds of the EuroMillions game “depend on how many prizes are offered and how many tickets are sold, so they are always different.” Then I saw this page with a table of odds for the UK Lotto game and realized that I didn’t know how to reproduce it. That was kind of embarrassing, so I decided to dig in and force you to dig with me.

Here are the rules of the UK Lotto game: There are 59 balls, numbered 1–59. Six of these balls are chosen in a drawing. Players choose six numbers and win if two, three, four, five, or six of their numbers match the drawn balls.1 The winnings go up with more matches. It’s the same as the New York Lotto except that New York’s game doesn’t give out money for only two matches.

Six matches

The probability of matching all six balls was the one calculation I could do immediately. The number of ways to choose 6 items from a pool of 59 is

This is the number of combinations. It’s equal to the binomial coefficient, and there are different notations for it. I’m going to use for the balance of this post.

Since there’s only one way to match all 6 balls, the probability is

Lotteries like to express probabilities as “1 in n,” so this appears as “1 in 45,057,474” in the table.

Five matches

This is where I started having trouble. The probability of getting 5 matches is not . The lottery math page on Wikipedia gives the right formula,

but I didn’t think much of its explanation. Other explanations I found in combinatorics texts didn’t fit with my way of thinking, either, but after reading a few, I was able to put together an explanation that stuck:

Separate the 59 balls into two groups: the “good” group consists of the 6 balls selected in the drawing and the “bad” group consists of the 53 other balls. My ticket has 6 numbers on it, 5 of which are in the good group and 1 is in the bad group. (I’ve emphasized the and because we’ll return to it soon.) The number of ways of getting 5 items from a group of 6 is

The number of ways of getting one item from a group of 53 is

In set theory and probability, and implies multiplication, so there are

ways to get exactly 5 matches on my ticket. Therefore, the probability of getting exactly 5 matches is

There is no way to further reduce the fraction in this formula, so a lottery would express this as “1 in 141,690.17” or maybe just “1 in 141,690.”

Four matches

Now that I understand the formula, I can apply it again and again. For exactly four matching numbers, the probability is

which can be expressed as “1 in 2,179.85” or “1 in 2,180.”

Three matches

Here, the probability is

which can be expressed as “1 in 96.17” or “1 in 96,” although rounding to just two digits might be a little too much.

Two matches

This probability is

which can be expressed as “1 in 10.26” or “1 in 10.3.”

The bonus ball

The values calculated above match the odds table for 6, 4, 3, and 2 matches, but not for 5 matches or “5 numbers + Bonus Ball.” What’s that about?

As mentioned in the footnote above, there’s an additional wrinkle to the game. After the six good balls are drawn, a seventh “bonus ball” is drawn from the remaining 53 balls. If five of the numbers on your ticket match five of the six good balls, you get a chance to match the bonus ball. If your bad number matches the bonus ball, that pushes you up into the “5 numbers + Bonus Ball” tier; if it doesn’t, you stay in the “5 numbers” tier.

So if you matched five of the original six numbers, the probability of your bad number matching the bonus ball is simply and the overall probability of getting into this tier is

which is the “1 in 7,509,579” shown in the table.

Similarly, the probability of your one bad number not matching the bonus ball is , so the overall probability of being in the “5 numbers” tier is

which is “1 in 144,414.98” or “1 in 144,415,” as shown in the table.

Final comments

Although the number of combinations is always an integer, the “1 in n” odds presented by lotteries are often rounded to the nearest integer, at least if n is large. I’d never realized that before.

In Mathematica, the Binomial function is the way to calculate . In Python, it’s the comb function in the math library. Both of these can return values well beyond the limit of 64-bit integers.

Learning how lottery odds are calculated may not be the best way to stave off senility, but it beats doing crossword puzzles.

-

There’s an additional wrinkle involving a “bonus ball,” but we’ll get to that later. ↩