Fixing a physics problem

January 14, 2026 at 2:33 PM by Dr. Drang

I’ve been bothered by this little physics problem for a couple of days. It appeared on Rhett Allain’s Medium site on Monday, and he linked to it on Mastodon. Prof. Allain teaches at Southeastern Louisiana University and writes on physics for Wired. I like reading his stuff, but this time he misses the main feature of the problem he’s trying to solve. So…

The problem is based on this video he ran across on Threads. It shows a rock climber slipping and being halted in his fall by the rope that connects him and his belayer. Here are a few frames from the video (you may want to zoom in):

The left frame is when the climber slips and starts to fall. The rope that connects him to the belayer on the ground passes through a metal ring that the black arrow is pointing to. The middle frame is when the rope becomes taut and the belayer starts being pulled up. The right frame is where the simple part of their motion stops. They come together and start using their feet against the cliff; they also start swinging sideways. Elementary physics is not going to help us describe the motion after this.

You might pick slightly different frames for each of these points, but I don’t think we’d be too far off from one another.

Prof. Allain idealizes the situation this way:

- The climber and belayer start at rest.

- The climber and belayer end at rest at the same elevation.

- The climber and belayer weigh the same.

- There is no energy lost through friction as the rope passes through the ring.

With these assumptions, he calculates that the final elevation of the climber and belayer is half the original elevation of the climber, an answer that he immediately recognizes as wrong.

You might think that my objection to his solution is Assumptions 3 and 4, but I have no problem with either of them. Even if you know they’re wrong, using simplifying assumptions like this is usually a good way to start. You can always add complications after you have a handle on the problem.

No, my objection to his solution lies with Assumption 2 and a constraint that he ignores entirely. While the climber and belayer do end up at about the same elevation, it’s not because they come to a halt naturally; it’s because they run into each other. And the elevation they’re at when they come together is determined by the height of the ring and the length of the rope. After the rope becomes taut—and before they collide—the descent speed of the climber and the ascent speed of the belayer are equal. That is a key constraint on the system that any solution must account for.

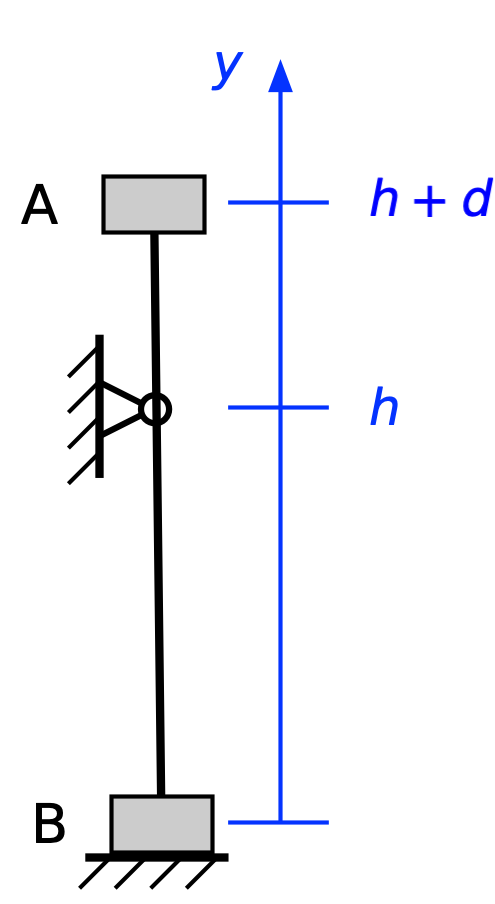

Let’s do this problem with Assumptions 1, 3, and 4. Here’s the starting position:

Our y axis starts at the center of gravity of the belayer, B. The height of the ring is h, and the climber is a distance d above the ring. I’m adding another assumption here: that the belayer is playing out rope as the climber ascends, keeping almost no slack in the rope. That would be the safe way to deal with the rope, and it looks like there’s little slack in the rope before the fall. You can see that if you look at the video itself instead of my reduced-size frame grabs. I should mention that the climber is not directly above the ring, which introduces some angles that I’m going to ignore. Including them would not change the principles of the following analysis but would cloud the principles by making the math more complicated.

The gravitational potential energy at this point is

where m is the mass of the climber and g is the acceleration due to gravity. As Prof. Allain says, there’s no kinetic energy in the system before the climber falls: .

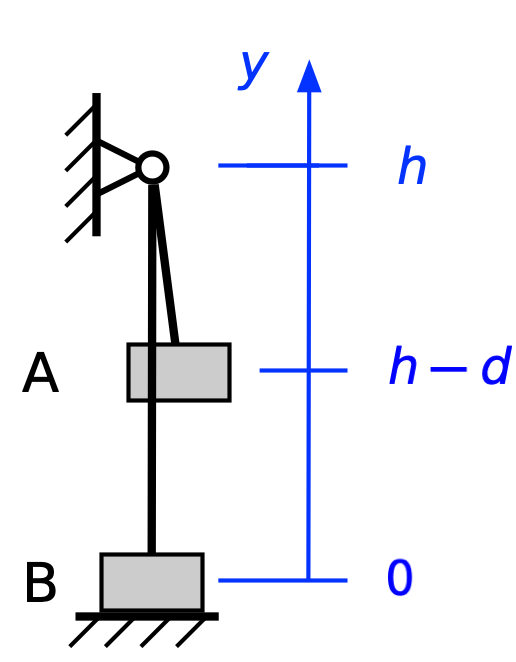

Now let’s consider the point at which the rope becomes taut again. The climber has been in free fall between the initial position and this point:

Let’s not worry about horizontal positioning here. Now the potential energy is

and because the total energy is conserved, the kinetic energy must be

which is obviously a positive value. We could, at this point, calculate the downward velocity of A, but we don’t need that information to continue the analysis.

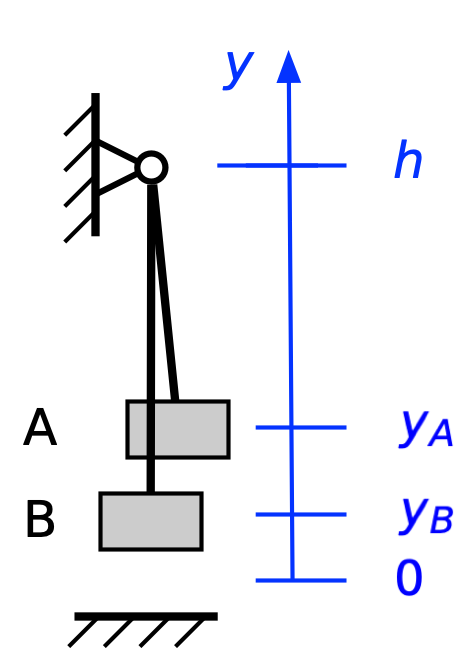

From now on, the constraint of the rope comes into play. Here’s a later position:

We’ll assume the rope is inextensible, which means

where L is the length of the rope. Rearranging, we get

The right-hand side of this equation is constant, so if we take the derivative of each side with respect to time, we get

What this means is that for every time interval from the point at which B lifts off the ground,

Since the two men are of equal weight,

so the potential energy remains constant after B lifts off the ground.

Since the potential energy remains constant, the kinetic energy must remain constant, too, and the two will continue their motion. To come to a stop, they must remove kinetic energy by way of

- a collision with each other;

- striking/rubbing the cliff wall; or

- friction of the rope against the ring.

All three of these can play a role.

To me, the key feature of this problem is the constancy of the gravitational potential energy after the rope becomes taut, and that constancy comes from the constraint provided by the rope. Without considering that constraint, you cannot explain the behavior.

What if the two men don’t weigh the same? If the climber weighs more, the potential energy decreases as he moves down and the belayer moves up, which means the kinetic energy increases. If the belayer weighs more, the opposite is true. We’ll look at this more complicated problem in a later post.