Freezing pipes

January 21, 2026 at 4:03 PM by Dr. Drang

The Midwest is expected to have very cold temperatures this weekend, which got me thinking about burst water pipes. Water expands about 9% as it freezes, and a lot of people think it’s pressure from the outward expansion of ice that ruptures pipes, but it’s more complicated than that.

My favorite reference for this phenomenon is this 1996 paper by Jeffrey R. Gordon of the Building Research Council at the University of Illinois. It’s entitled “An Investigation into Freezing and Bursting Water Pipes in Residential Construction,” and it goes through the testing that the BRC did on behalf of the Insurance Institute for Property Loss Reduction.

Why do I have a favorite reference for burst pipes? I used to get hired by insurance companies to investigate burst pipes and the subsequent damage in high-end residences. When the pipe failed in a heated area, it was nice to have this paper to back up my explanation of how freezing in one part of a pipe can lead to failure in another. Also, the report is quite easy to read. There’s not a lot of jargon, and you don’t need much scientific or engineering background to understand it.

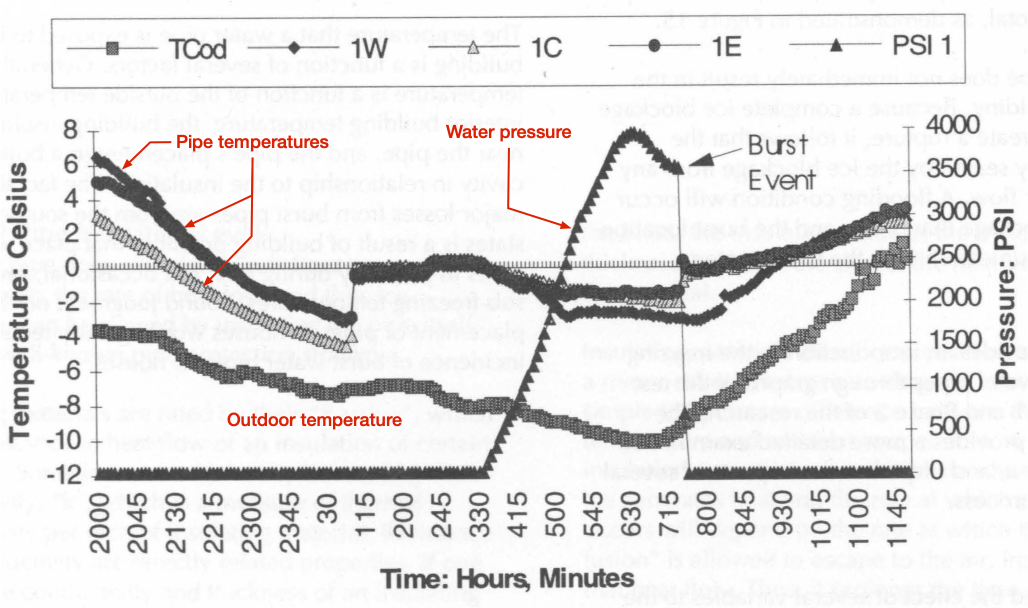

Here’s Figure 15 from the report, which graphs the data collected during the testing of a 3/4″ copper pipe running through an unheated attic. The pipe was instrumented with thermocouples to capture its temperature at three locations and a pressure gauge to capture the water pressure inside it. The red annotations are mine. As you can see, the pressure rose to about 4,000 psi, at which point the pipe bulged—that’s the drop in pressure as the pipe increased in diameter and decreased in wall thickness—and then burst.

The best explanation of what happened in the test—and what commonly happens in real-world pipe bursts—comes from the report itself:

This shows the central, and often least understood, fact about burst water pipes: freezing water pipes do not burst directly from physical pressure applied by growing ice, but from excessive water pressure. Before a complete ice blockage, the fact that water is freezing within a pipe does not, by itself, endanger the pipe. When a pipe is still open to the water system upstream, ice growth exerts no pressure on the pipe because the volumetric expansion caused by freezing is absorbed by the larger water system. A pipe that is open on one end cannot be pressurized, and thus will not burst.

Once ice growth forms a complete blockage in a water pipe the situation changes dramatically. The downstream portion of the pipe, between the ice blockage and a closed outlet (faucet, shower, etc.) is now a confined pipe section. A pipe section that is closed on both ends can be dramatically pressurized, water being an essentially incompressible fluid. If ice continues to form in the confined pipe section, the volumetric expansion from freezing results in rapidly increasing water pressure between the blockage and the closed outlet. As figure 15 shows, the water pressure in a confined pipe section can build to thousands of pounds per square inch.

Read that second paragraph again. It’s really a perfect explanation of how, for example, a pipe or joint under a bathroom sink can fail even though that part of the pipe was never exposed to freezing temperatures. It’s the ice buildup in the pipe elsewhere—typically in an unheated area on the other side of the drywall—and the continued growth of ice in the isolated zone between that blockage and the faucet at the sink that leads to a huge increase in pressure. The pipe will fail at whatever point is weakest within that zone.

Which leads to some common advice given when temperatures are going to drop.

- For sinks up against an outside wall, leave the cabinet doors open so the warm air of the house gets a chance to circulate around the pipes. You want them to get as much exposure to warm air as possible so they can conduct that heat to the colder parts on the other side of the drywall.

- Open faucets that are against an outside wall and let them drip. I’ve never done this because I added extra insulation around and on the cold side of my pipes many years ago, but it can help. Not, as some people say, because moving water doesn’t freeze (have they never seen a river frozen over?) but because a slightly open valve prevents the buildup of pressure shown in Figure 15. As the report says, “A pipe that is open on one end cannot be pressurized, and thus will not burst.”