Easy to be hard

February 19, 2026 at 6:25 PM by Dr. Drang

Here’s a geometry puzzle from the March issue of Scientific American. If you see the trick, it’s easy to solve.1 After doing it the easy way, I decided to solve it again the hard way, as if I hadn’t noticed the trick.

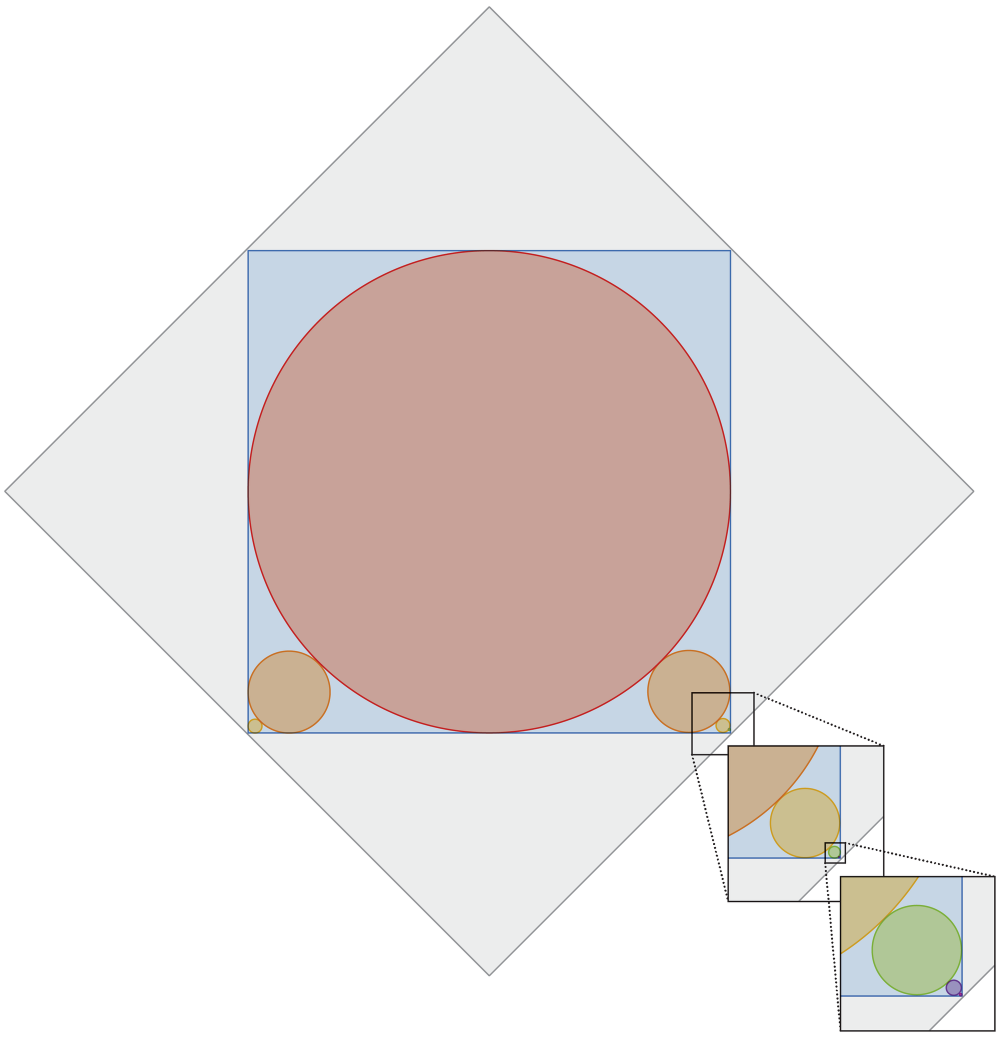

Here’s the puzzle:

A red circle is inscribed inside a blue square. The arrangement leaves gaps in the square’s four corners, two of which are filled with smaller circles that just barely touch the big red circle and the two corner sides of the blue square. This, in turn, leaves two smaller gaps in the corners, which are filled with smaller circles, and so on, with ever smaller circles ad infinitum. The entire diagram is inscribed inside of a 1 × 1 gray square. What is the total circumference of all the circles?

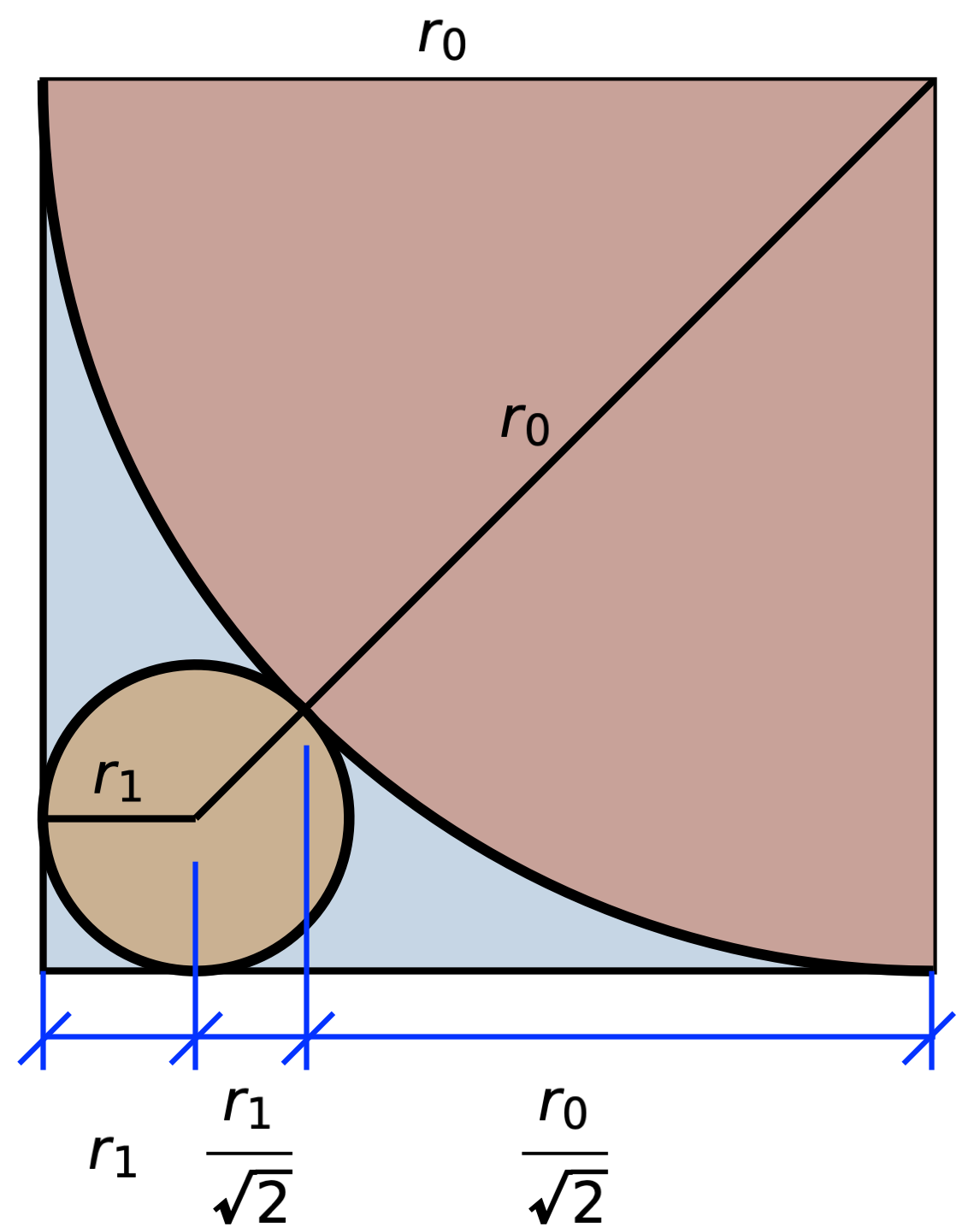

Without the trick, we’re going to have to work out all the circumferences and add them together. We’ll start by figuring out the relationship between the radii of consecutive circles. Here’s a quarter of the largest circle, the radius of which we’ll call , and the next largest circle, the radius of which we’ll call :

From this drawing, we can express the width in two ways and set them equal to one another:

Multiplying through by and rearranging, we get

I want to turn this into a fraction with a 1 in the numerator, so I’ll multiply the top and bottom by an expression that will eliminate the square root in the numerator:

This relationship also holds for any two consecutive circles,

which means we can express the radius of the ith circle in terms of the radius of the largest circle:

So the sum of all the circumferences is times the sum of all the radii:

Note that there’s only one circle with radius , but two circles for all the other radii.

By the way, this expression is where it’s helpful to have the fraction inside the sum written with a 1 in the numerator. We know that

converges, so our fraction, which has a larger denominator, must also converge.

We’re nearly there. Recall that the gray square (the one that’s rotated 45°) has a side length of 1. That means

so the sum of the circumferences is

Now for a confession: I have always stunk at working out infinite series. Luckily, I can now lean on a computational cane. Here’s a Mathematica expression that will return the infinite sum:

Pi/Sqrt[2] (1 + 2 Sum[1/(3 + 2 Sqrt[2])^i, {i, 1, Infinity}])

The answer, as we know from doing it the easy way, is .

If I didn’t have Mathematica, I’d probably set up a finite series for the expression without ,

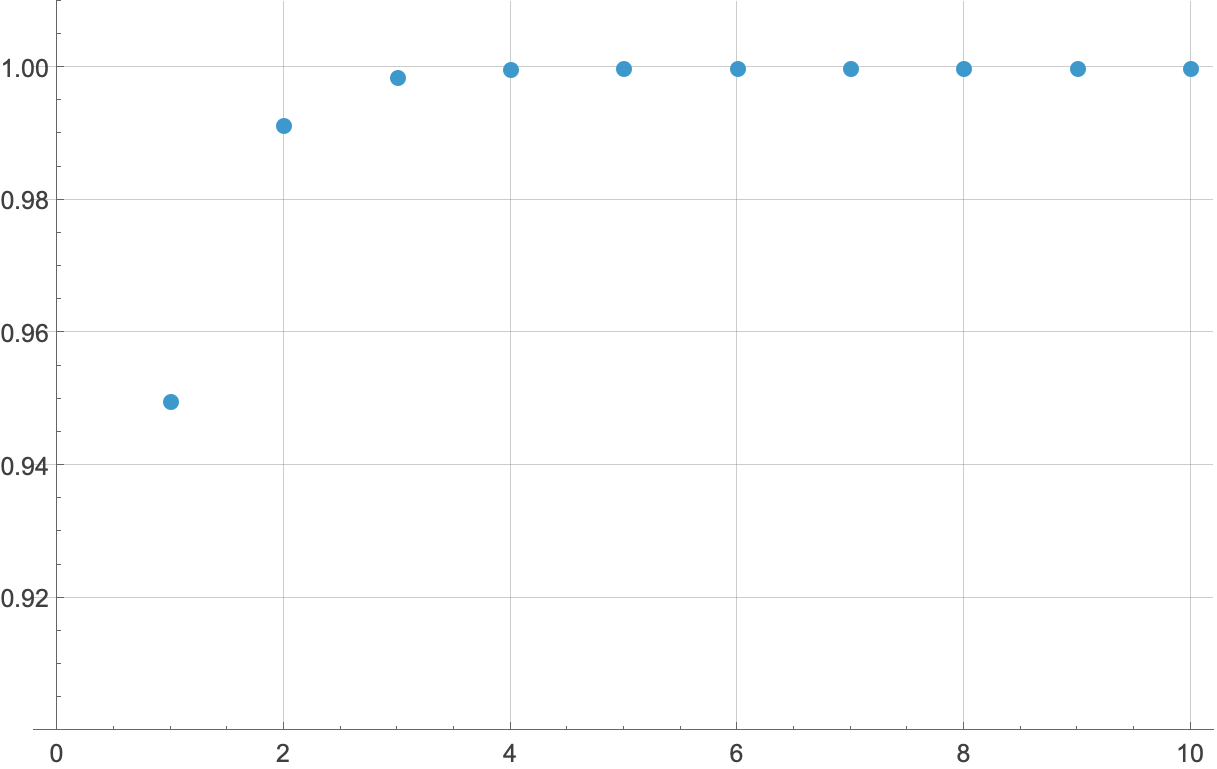

and run out the calculations for different values of n to see where it converges. We can show the results as a table,

| n | Sum |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.94974747 |

| 2 | 0.99137803 |

| 3 | 0.99852070 |

| 4 | 0.99974619 |

| 5 | 0.99995645 |

| 6 | 0.99999253 |

| 7 | 0.99999872 |

| 8 | 0.99999978 |

| 9 | 0.99999996 |

| 10 | 0.99999999 |

or as a plot,

Either way, going out ten terms is overkill—it’s obvious that the sum is converging to 1, which means the circumference sum is converging to . You can, I guess, consider this numerical exercise as a check on Mathematica’s work. Or a check on the easy solution.

-

SciAm also uses the trick in its solution, which you won’t see if you click on the link in this paragraph. It’s one link further away. ↩