Mac screenshots for the nth time

October 6, 2025 at 2:33 PM by Dr. Drang

After building my iPhone screenshot framing system, I decided to tackle the problem of Mac screenshots. I’ve been using CleanShot X for a while, but the small annoyances that come with using it have been weighing on me, and it seemed like a good time to return to a system built especially for my needs.

I have some very particular ideas about how Mac screenshots should look. They shouldn’t include the shadow, as that takes up too much space and detracts from the window itself.1 They do, however, need some sort of border if you’re putting them on a white background; otherwise, the screenshot looks incomplete. I like adding relatively thin solid color around my window screenshots so they look like they’re on my Desktop. My wallpaper is a solid dull blue, so that’s what I use for my window screenshot borders. Finally, the window corners should be rounded just as I see them on my screen.

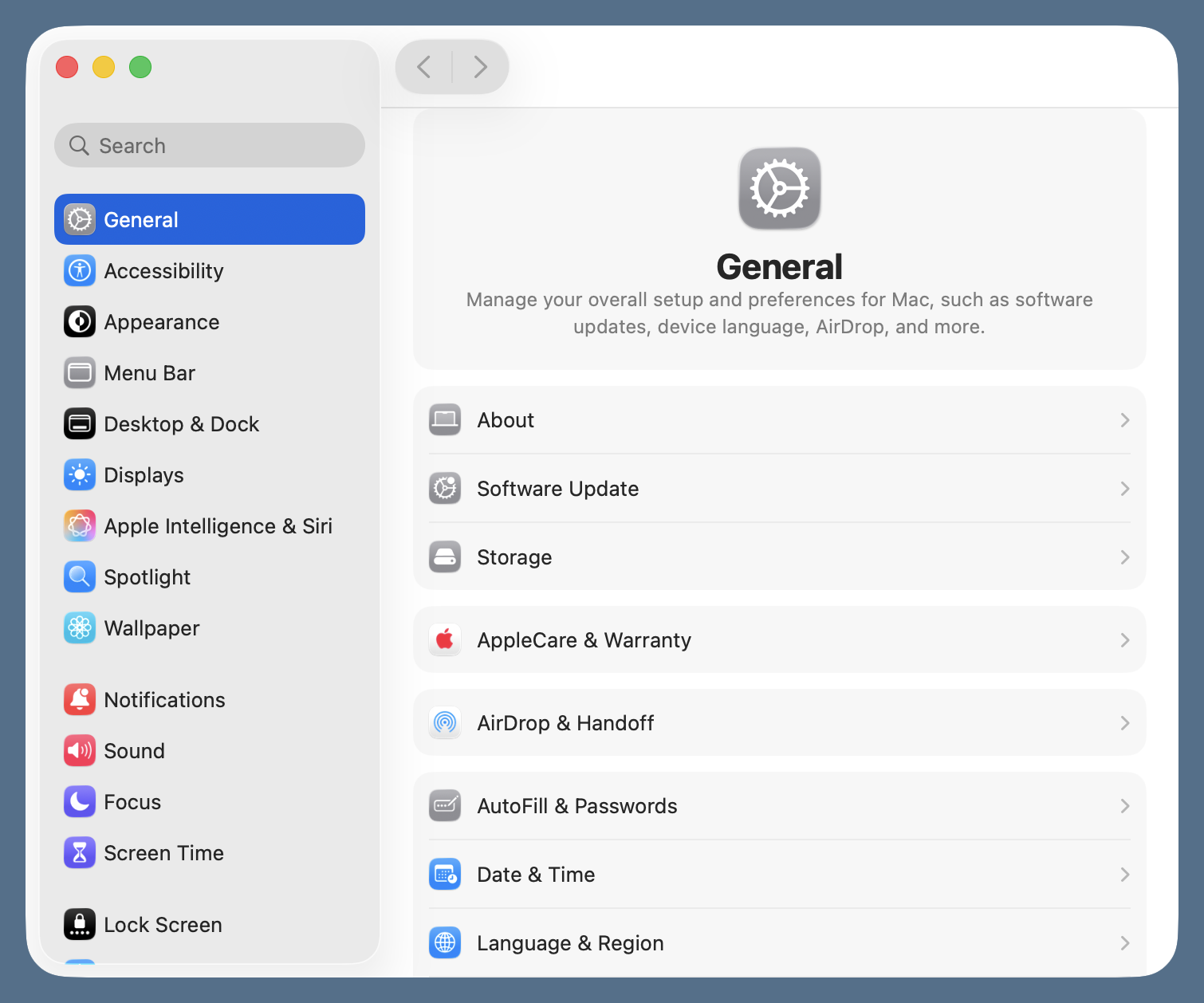

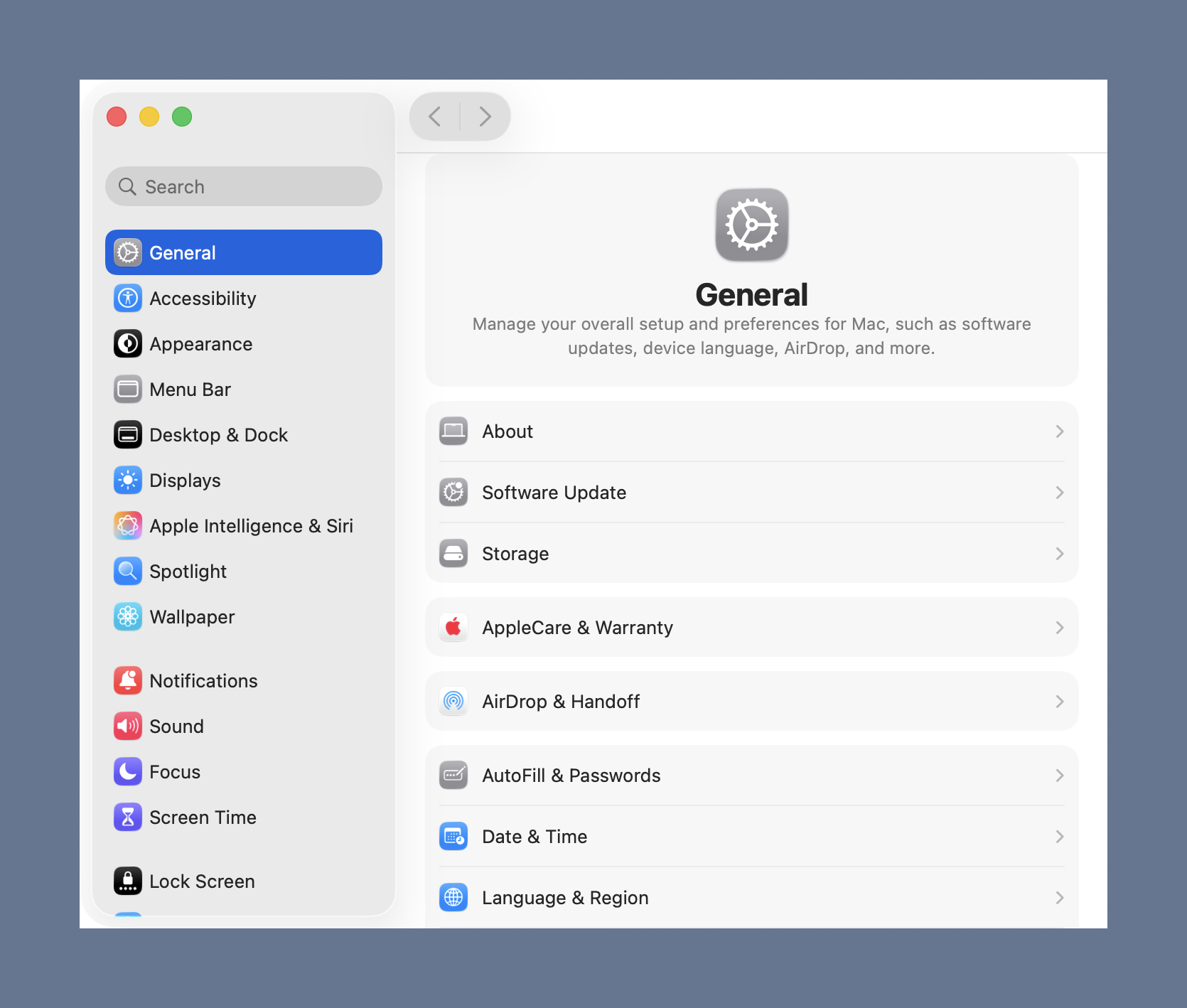

CleanShot X’s window screenshots don’t meet these particulars. It’s not hard to tweak things—either during the screenshot or through postprocessing—to get what I want, but I’m tired of doing the tweaks. The smallest border CleanShot X will give is much larger than I want. And for some reason, the window corners are squared off, not rounded. This, I learned, got especially noticeable with Tahoe’s especially rounded corners. As an example, here are two screenshots of the Tahoe System Settings window.

The first is what I want:

The second is what CleanShot X gives by default:

One way to get around this in CleanShot X is to take a rectangular selection screenshot instead of a window screenshot. But that typically means hiding all the other windows on my screen and then being careful as I drag out the rectangular selection. I’ve had enough of the extra effort.

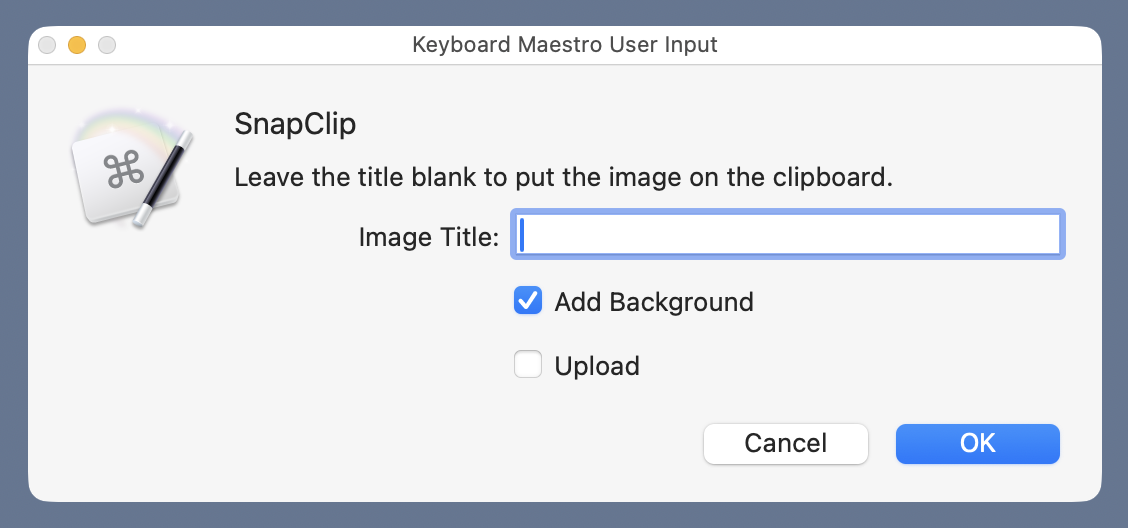

Instead, I put my effort into writing code that does exactly what I want. The result is a Keyboard Maestro macro called SnapClip that puts up this window:

After I set the options, the cursor turns into a camera. I place it over the window I want a screenshot of and click. Depending on the options, the screenshot will either be on my clipboard, saved to the Desktop, or saved to the Desktop and uploaded to the leancrew server. (Turning the option off is for taking rectangular selection screenshots, which I can switch to by pressing the space bar.)

If you’ve been reading ANIAT for a while, you may remember that I’ve had different versions of SnapClip over the years. This is a new one. Some of its components were lifted straight from the old versions, some were adapted from old code, and some are brand new. I’m not going to link to any of my old screenshot code—you can search the archives as well as I can.

The main work is done by a Python script, called screenshot. It can be called from the Terminal with options that match up with the SnapClip options shown above. Here’s the help message for screenshot:

usage: screenshot [-h] [-b] [-u] [-t TITLE]

Like ⇧⌘4, but with more options.

options:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-b, --background add desktop background border

-u, --upload upload to images directory and print URL

-t, --title TITLE image title

Starts in window capture mode and can add a border to the

screenshot. If a title is given, it saves the image to a file

on the Desktop with a filename of the form yyyymmdd-title.png.

If no title is given, the image is put on the clipboard and the

upload option is ignored.

And here’s the source code:

python:

1: #!/usr/bin/env python3

2:

3: import tempfile

4: from PIL import Image

5: import os

6: import subprocess

7: import shutil

8: from datetime import datetime

9: import urllib.parse

10: import argparse

11:

12: # Handle the arguments

13: desc = 'Like ⇧⌘4, but with more options.'

14: ep = '''Starts in window capture mode and can add a border to the

15: screenshot. If a title is given, it saves the image to a file

16: on the Desktop with a filename of the form yyyymmdd-title.png.

17: If no title is given, the image is put on the clipboard and the

18: upload option is ignored.'''

19: parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description=desc, epilog=ep,

20: formatter_class=argparse.RawDescriptionHelpFormatter)

21: parser.add_argument('-b', '--background', help='add desktop background border', action='store_true')

22: parser.add_argument('-u', '--upload', help='upload to images directory and print URL', action='store_true')

23: parser.add_argument('-t', '--title', help='image title', type=str)

24: args = parser.parse_args()

25:

26: # Parameters

27: type = "png"

28: localdir = os.environ['HOME'] + "/Pictures/Screenshots"

29: tf, tfname = tempfile.mkstemp(suffix='.'+type, dir=localdir)

30: bgcolor = (85, 111, 137)

31: border = 32

32: optimizer = '/Applications/ImageOptim.app/Contents/MacOS/ImageOptim'

33:

34: # Capture a portion of the screen and save it to a temporary file

35: status = subprocess.run(["screencapture", "-iWo", "-t", type, tfname])

36:

37: # Add a desktop background border if asked for

38: if args.background:

39: snap = Image.open(tfname)

40: # Make a solid-colored background bigger than the screenshot.

41: snapsize = tuple([ x + 2*border for x in snap.size ])

42: bg = Image.new('RGBA', snapsize, bgcolor)

43: bg.alpha_composite(snap, dest=(border, border))

44: bg.save(tfname)

45:

46: # Optimize the file

47: subprocess.run([optimizer, tfname], stderr=subprocess.DEVNULL)

48:

49: # Save it to a Desktop file if a title was given; otherwise,

50: # save it to the clipboard

51: if args.title:

52: sdate = datetime.now().strftime("%Y%m%d")

53: desktop = os.environ['HOME'] + "/Desktop/"

54: fname = f'{desktop}{sdate}-{args.title}.{type}'

55: shutil.copyfile(tfname, fname)

56: bname = os.path.basename(fname)

57:

58: # Upload the file and print the URL if asked

59: if args.upload:

60: year = datetime.now().strftime("%Y")

61: server = f'user@server.com:path/to/images{year}/'

62: port = '123456789'

63: subprocess.run(['scp', '-P', port, fname, server])

64: bname = urllib.parse.quote(bname)

65: print(f'https://leancrew.com/all-this/images{year}/{bname}')

66: else:

67: subprocess.call(['impbcopy', tfname])

68:

69: # Delete the temporary file

70: os.remove(tfname)

There’s a lot going on in those 70 lines. Let’s go through them a chunk at a time.

Lines 13–24 use the argparse module to process the options. I’ve always shied away from argparse. It seemed more complicated than necessary, so I used docopt instead. But after reading this tutorial, I decided to give it a go. It wasn’t as complicated as I thought, and you can probably work out what it does without much commentary from me. I will say the following:

- The

-hand--helpoptions and the help message are created automatically byargparse. That’s why you don’t see any code that builds or prints the list of options. - The

descriptionis the optional part of the help message that comes between the usage and options sections. - The

epilogis the optional part that comes after the options section. - Creating the

ArgumentParserwithRawDescriptionHelpFormatteras theformatter_classmeans that thedescriptionandepilogare printed as-is, without line wrapping. I used this to make sure the filename format string,yyyymmdd-title.png, didn’t get broken over two lines.

Lines 27–32 define a set of parameters that will be used later in the script. We’ll talk about them as they come up.

Line 35 calls the screencapture command. This is a macOS command that works sort of like a combination of ⇧⌘3 and ⇧⌘4, but with more options. It’s called with -i, which puts it in interactive mode; -W, which starts it in window selection mode instead of rectangular selection mode; -o, which keeps the shadow out of the screenshot if a window is captured; and -t, which sets the type of the resulting image file. The argument of -t is the filetype, which is defined as png in Line 27. The final argument, tfname, is the file where the screenshot is saved. The file name is defined in Lines 27–29 with the help of the tempfile module.

At this point, we have a temporary file with the screenshot. The rest of the code processes it.

Lines 38–44 add a background border if the -b option to screenshot was given. The Python Imaging Library (PIL) opens the temporary file just created, makes a new rectangular image that’s larger than the screenshot by border (defined on Line 31) on all sides. This rectangle is filled with my Desktop color, bgcolor, an RGB tuple defined on Line 30. The two images are then composited together, honoring the alpha channel in the screenshot image. The result is saved back into the temporary file.

Line 47 uses the ImageOptim app to make the PNG file smaller. I do this to be a good web citizen. Although ImageOptim is a GUI application, it has a command line program buried in its package contents. The path to that program, stored in the variable optimizer, is defined on Line 32. You’ll note that the call to subprocess.run includes a directive to send the standard error output to /dev/null. That’s because the ImageOptim command generates a long diagnostic message as it processes the PNG and I don’t want that appearing when screenshot is run.

Lines 51–67 put the newly optimized image file somewhere. If the -t option was used, the image file is saved to the Desktop with a filename determined by the date and the -t argument. If the -t option wasn’t used, the image is put on the clipboard.

Putting the image on the clipboard requires a command that doesn’t come with macOS, impbcopy. This is a lovely little utility written about a decade ago by Alec Jacobson. It’s basically an image analog to the built-in pbcopy command, which only works with text. impbcopy takes an image file as its argument and puts the image on the clipboard.

If the -u option was used, the file is uploaded to my server via the scp command and the URL of the image is printed. The upload parameters shown here in Lines 61 and 62 have been changed from the actual values. The upload code runs only if an image file was saved. If you run screenshot with -u but no -t option, the -u will be ignored.

You’ll note there’s nothing about SSH keys in the code. I confess I can’t remember whether this is unnecessary because of entries in my ~/.ssh directory, the Keychain Access app, or something else. I do remember granting access via SSH to my server many years ago, and every OS X/macOS upgrade since then has honored that.

Finally, Line 70 deletes the temporary file.

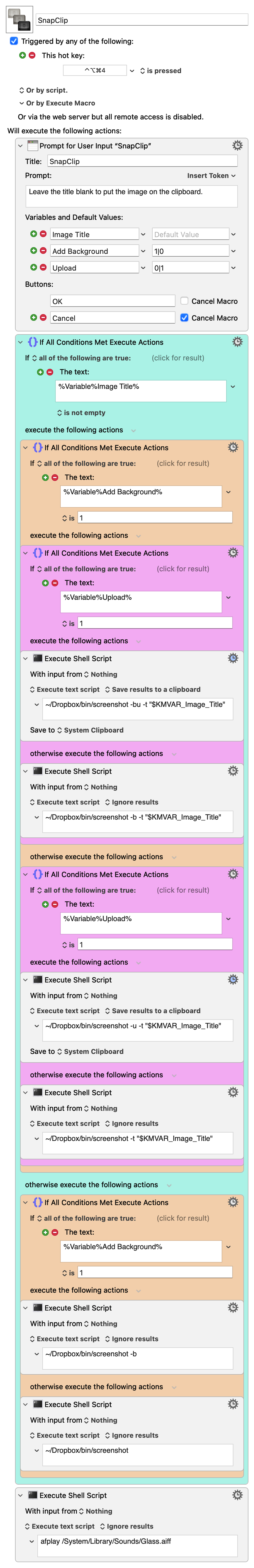

The SnapClip macro (which you can download) is just a GUI wrapper around screenshot. Here’s what it looks like:

Nested if statements are a pain to deal with in graphical coding environments like Keyboard Maestro. I gave the ifs different colors with the hope of making it easier to read, but I’m not convinced it’s much better. You might find this pseudocode easier to follow:

Show window with prompts for user input

If title

If background

If upload

screenshot -bu -t title

Else

screenshot -b -t title

Else

If upload

screenshot -u -t title

Else

screenshot -t title

Else

If background

screenshot -b

Else

screenshot

Play sound

A couple of notes on the macro:

- Long ago, I got in the habit of keeping the scripts I wrote in a

bindirectory in Dropbox. I probably should stop doing that, as iCloud syncing is fine, and I don’t use multiple Macs anymore. Anyway, that bit of history is why you see references to~/Dropbox/bin/screenshotin the macro. - Most of the calls to execute

screenshotare set to ignore the output. The exceptions are when the image file is uploaded. When that occurs,screenshotprints the URL of the uploaded image file, and that gets saved to the clipboard. - Although the

printfunction on Line 65 ofscreenshotadds a linefeed at the end of the URL, that linefeed won’t be on the clipboard when SnapClip is run. That’s because Keyboard Maestro is clever; it knows you probably don’t want the trailing linefeed and trims it automatically. (If you do want the linefeed, there’s a option in the gear menu to turn off the trimming.)

It’s entirely possible that I’ve missed some options in CleanShot X that would make its screenshots closer to what I want. I could also try another screenshot app, like Shottr, which Allison Sheridan has sung the praises of. But this new SnapClip handles everything I do with screenshots other than annotation (for which I use Acorn or OmniGraffle), so I’m not inclined to switch.

-

Don’t get me wrong, I like window shadows when I’m working. They help clarify the window stacking and have done so since the very beginning. But they’re unnecessary in a screenshot of a single window. ↩

Navigating Mathematica with Keyboard Maestro

October 3, 2025 at 4:23 PM by Dr. Drang

If you think I’ve written too much about Mathematica recently, don’t worry. This post discusses something in Mathematica that annoys me, but it isn’t really about Mathematica. It’s about how I eliminated that annoyance with Keyboard Maestro and how I should have done so long ago.

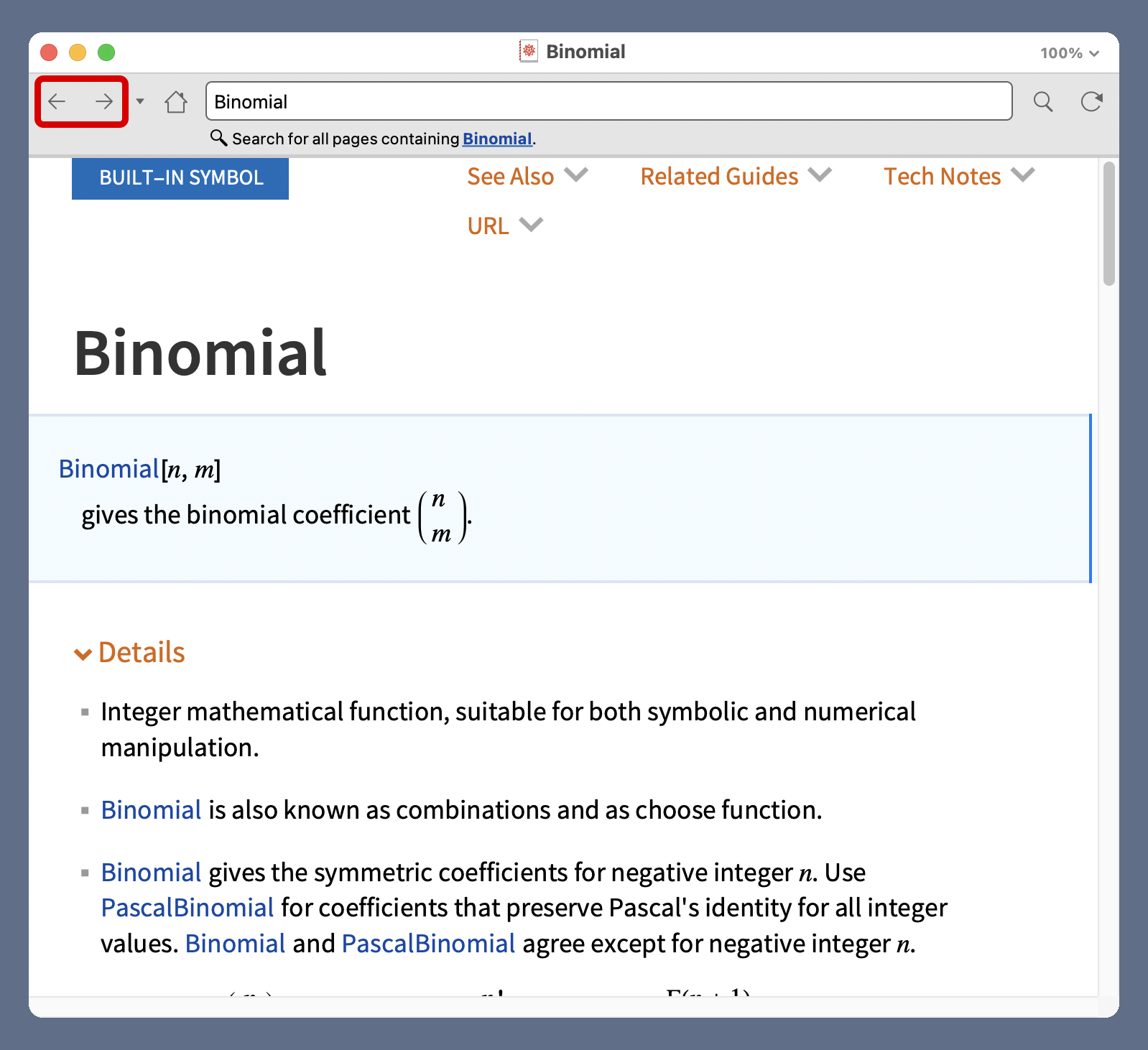

What I hate about Mathematica is navigating in its help window. Like Safari, the Mathematica help window has backward and forward navigation arrows up near the top left,

but unlike Safari, it doesn’t use the standard keyboard shortcuts of ⌘[ and ⌘] to navigate. Wolfram’s documentation says you can use “Alt ←” and “Alt →” to navigate, but those don’t work.1 If there’s a cursor blinking somewhere in the window, ⌥← and ⌥→ move the cursor left and right, which is standard Mac cursor control. If there’s no active cursor in the help window, ⌥← and ⌥→ do nothing.

And even if Mathematica worked the way its documentation says it works, and it overrode the standard behavior of ⌥← and ⌥→, I would never use them for navigation because my fingers don’t think that way. They want to use ⌘[ and ⌘] because that’s what Safari has trained them to use (also Firefox and Chrome).

Recently, during a particularly intense session with Mathematica’s help system, I got angry with myself. Why did I keep hitting ⌘[ and ⌘] and getting angry with Mathematica? Yes, Wolfram should adhere to Mac conventions, but you’re not powerless. Stop getting angry and fix the problem!

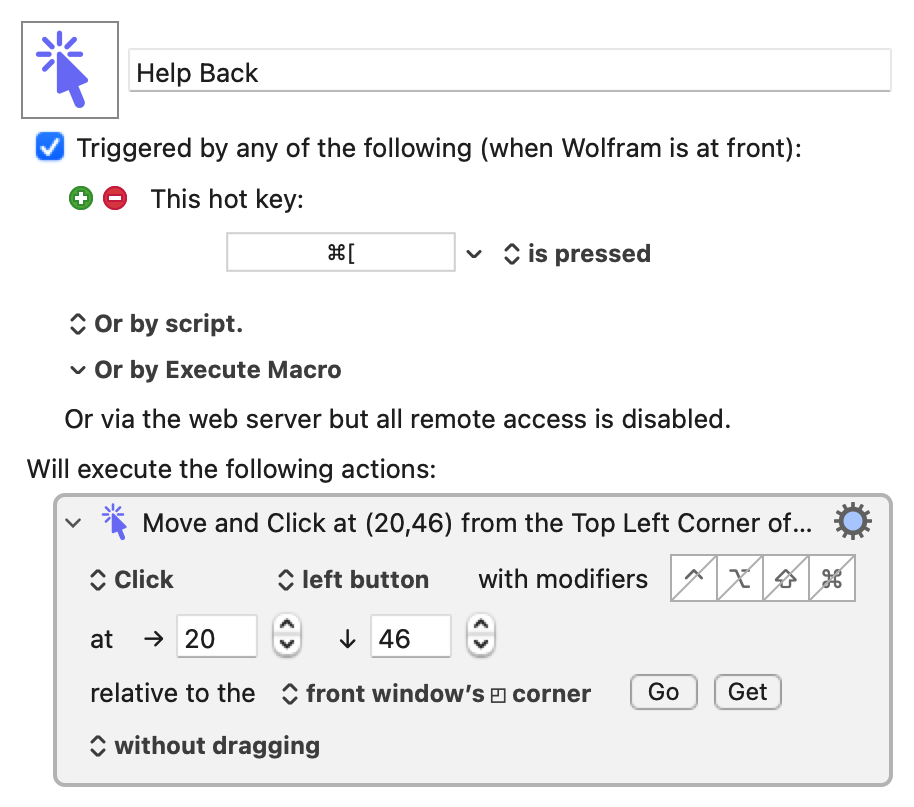

So I opened Keyboard Maestro and had a pair of one-step macros written in a few minutes. Here’s ,

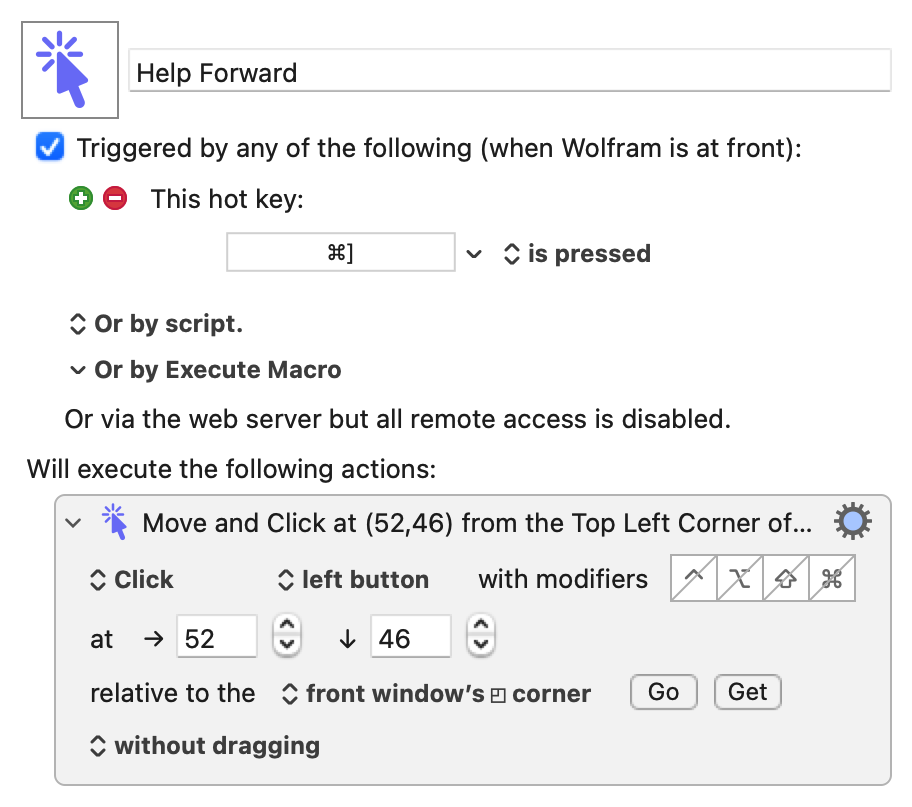

and here’s ,

They’re saved in Keyboard Maestro’s group, which means they work only when Mathematica is the active application.2

Initially, I tried to use Keyboard Maestro’s action, but that didn’t work consistently. Apparently, Mathematica’s arrow buttons are too anemic for Keyboard Maestro to find reliably. So I switched to and all was right with the world.

I should mention that the coordinates of the click with respect to the upper left corner of the window were determined with the help of the button. Click it and you have a five-second countdown (with beeps) to bring the appropriate window to the front and position the mouse where you want the click to happen. The coordinates fill in automatically. It’s one of those features that users love about Keyboard Maestro.

Now when my fingers press ⌘[ and ⌘], Mathematica’s help window responds the way it should, and I don’t get angry anymore. Except a little bit at myself for not doing this ages ago.

-

Normally, this is where I’d complain that Macs don’t have Alt keys, they have Option keys, but I’m going to let that pass. See how I’m letting that pass? ↩

-

Wolfram has really messed up its naming. The documentation calls the app either “Mathematica” or “Wolfram Mathematica,” depending on what part of the documentation you’re looking at. My account says I have a license for “Wolfram Mathematica.” The app’s icon and the menu bar when the app is running say it’s “Wolfram.” Keyboard Maestro goes with the name in the menu bar. ↩

Dot plots in Mathematica

October 2, 2025 at 5:52 PM by Dr. Drang

I ran across Mathematica’s NumberLinePlot function recently and wondered if I could use it to make dot plots. The answer was yes, but not directly.

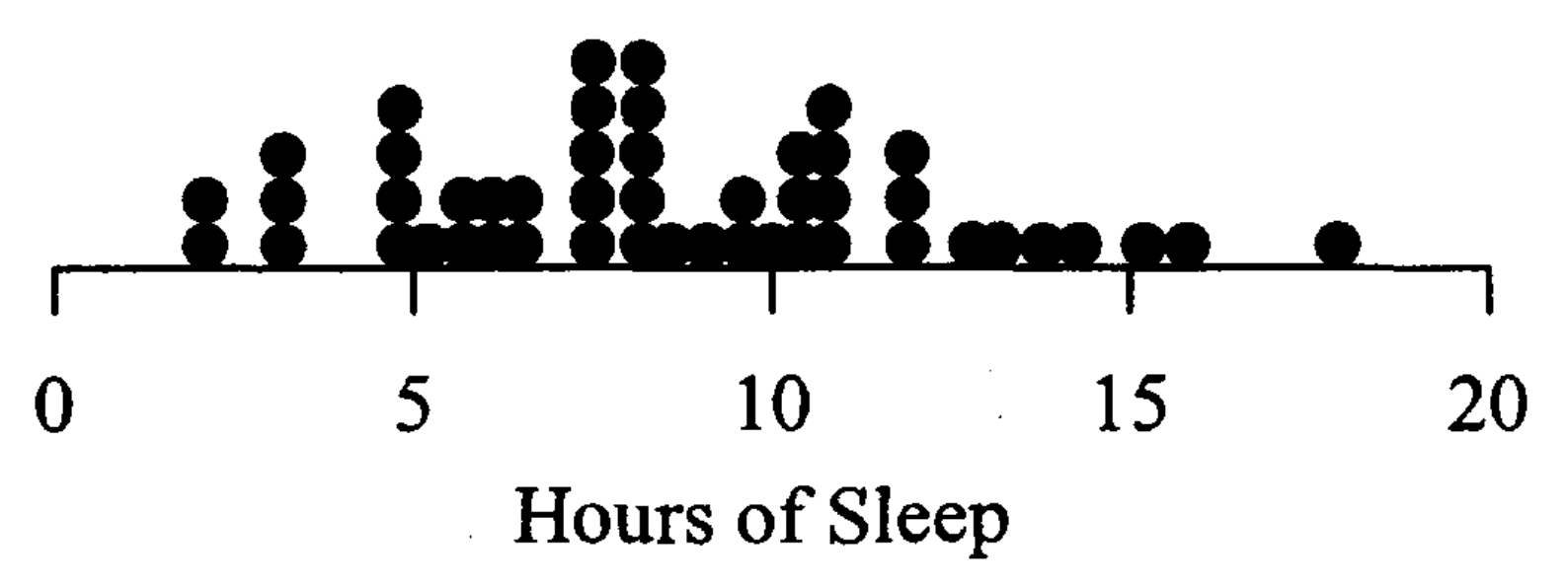

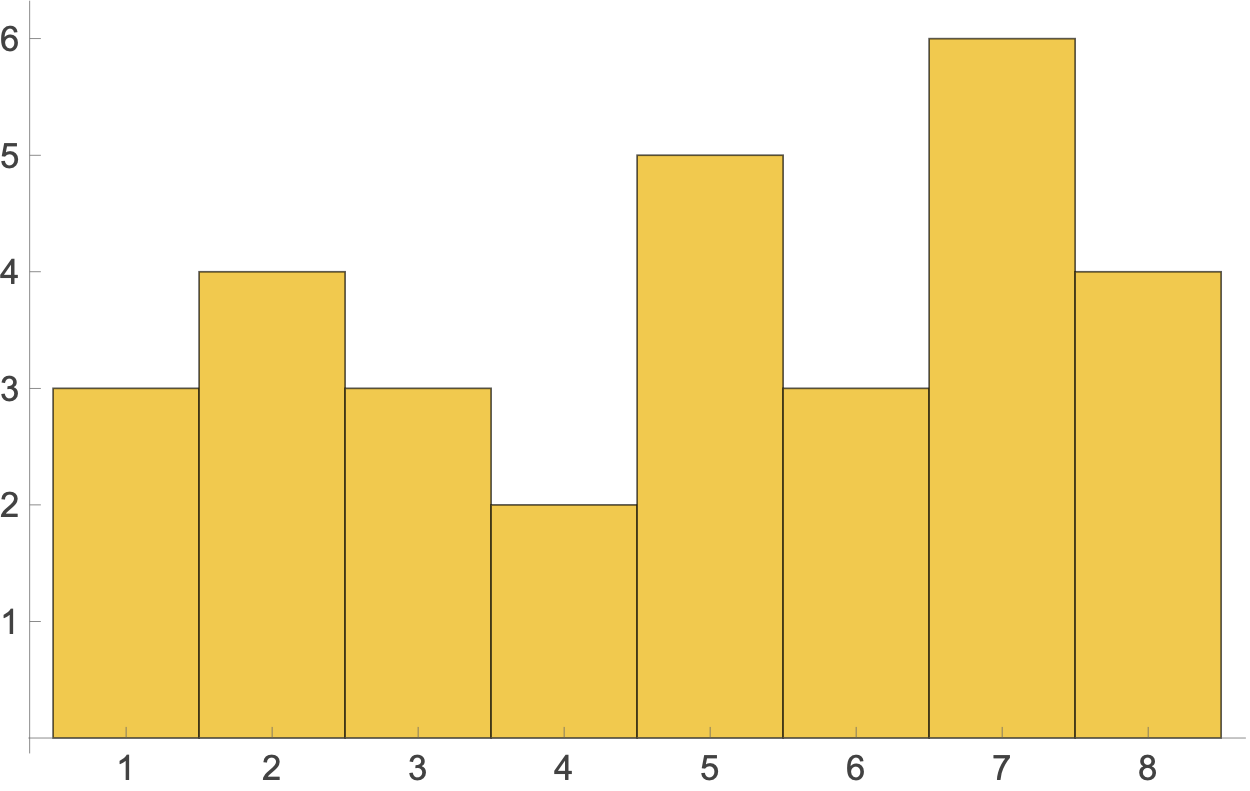

By “dot plots,” I mean the things that look sort of like histogram but with stacked dots instead of boxes to represent each count. Here’s an example from a nice paper on dot plots by Leland Wilkinson (the Grammar of Graphics guy):

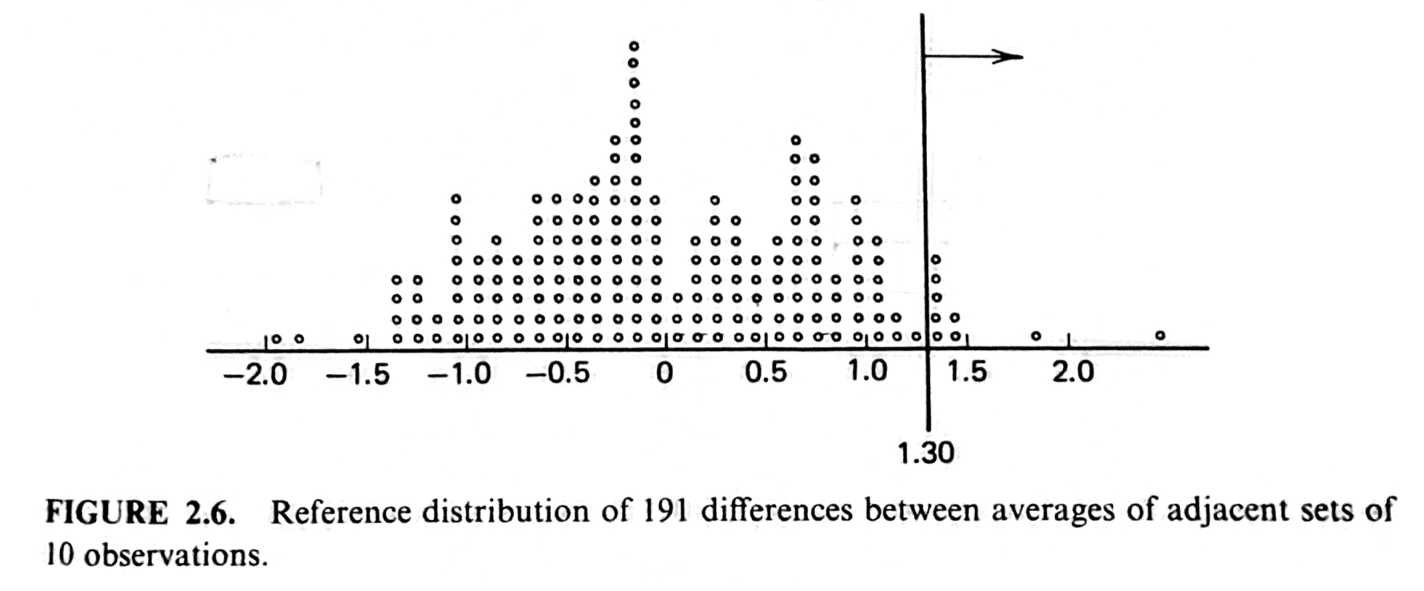

The paper is referenced in the Wikipedia article on dot plots, and rightly so. Here’s another in a slightly different style from Statistics for Experimenters by Box, Hunter, and Hunter (who call them dot diagrams):

(The vertical line and arrow are add-ons to the dot plot pertinent to the particular problem BH&H were discussing.)

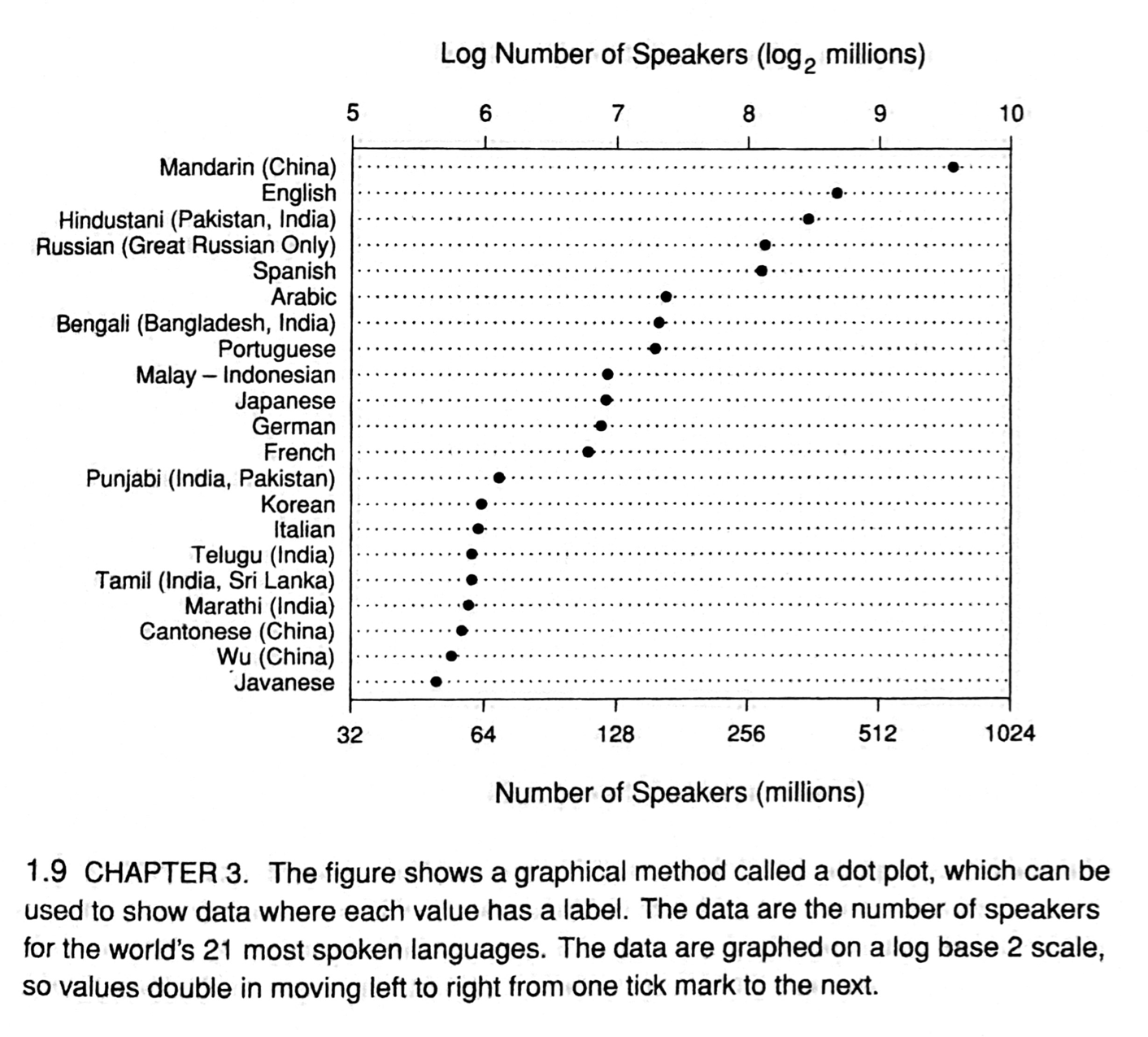

If you’re a William Cleveland fan, you should be aware that the kind of dot plots I’ll be talking about here are not what he calls dot plots. His dot plots are basically bar charts with dots where the ends of the bars would be. Like this example from The Elements of Graphing Data:

With that introduction out of the way, let’s talk about Wilkinson-style dot plots and NumberLinePlot.

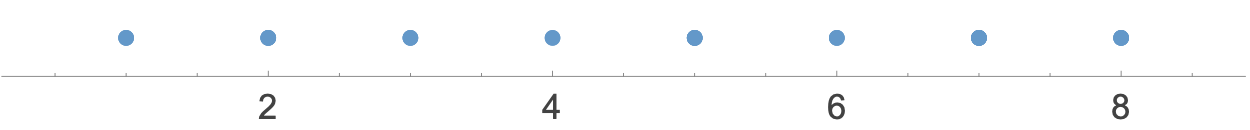

In a nutshell, NumberLinePlot takes a list of numbers and produces a graph in which the numbers are plotted as dots along a horizontal axis—very much like the number lines I learned about in elementary school. I wondered what it would do if some of the numbers were repeated, so I defined this list of 30 integers with a bunch of repeats,

a = {7, 2, 4, 8, 5, 7, 4, 2, 1, 3, 7, 5, 7, 8, 7,

2, 5, 6, 7, 6, 1, 5, 2, 1, 6, 5, 8, 3, 8, 3}

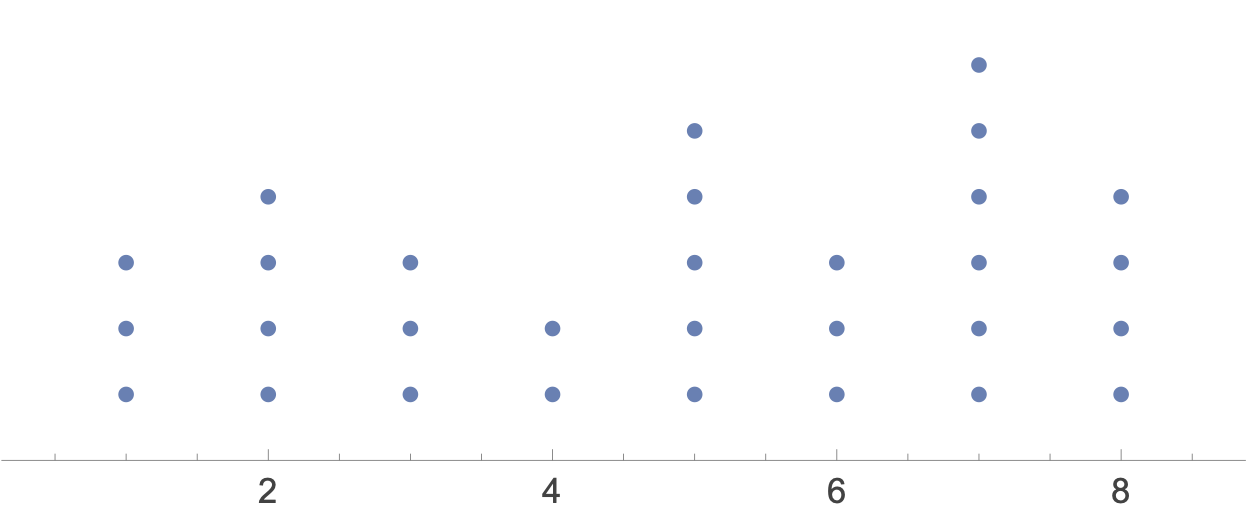

and ran NumberLinePlot[a]. Here’s the output:

Unfortunately, it plots the repeated numbers on top of one another so you can’t see how many repeats there are. I looked through the documentation to see if I could pass an option to NumberLinePlot to get it to stack the repeated dots vertically, but no go.

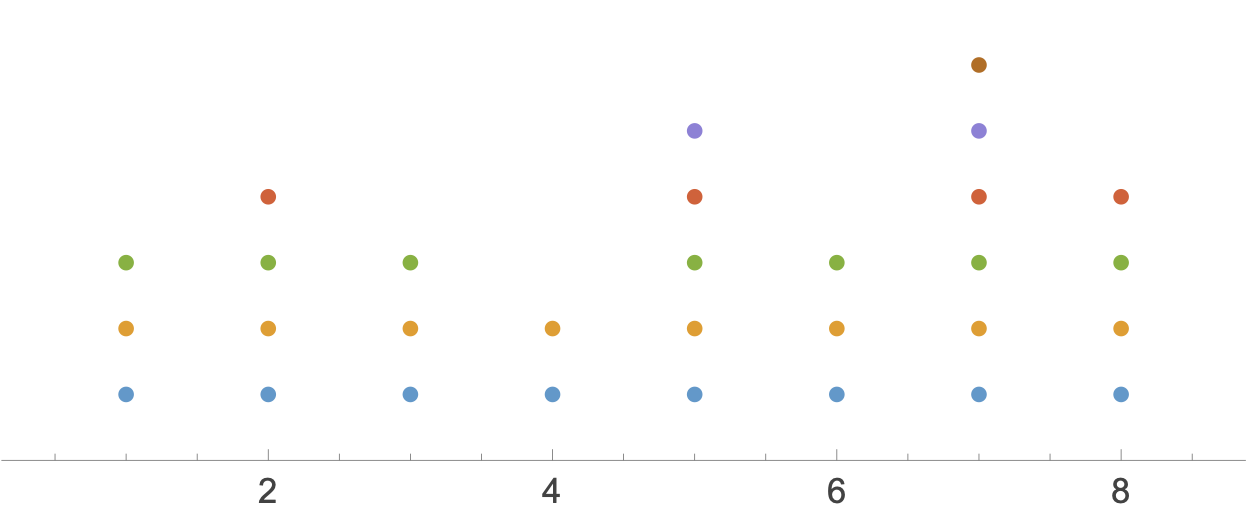

There is, however, a way to get NumberLinePlot to stack dots. You have to pass it a nested list set up with sublists having no repeated elements. For example, if we rewrite our original flat list, a, this way,

b = {{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8},

{1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8}, {2, 5, 7, 8}, {5, 7}, {7}}

and run NumberLinePlot[b], we get this graph:

As you can see, each sublist is plotted as its own row. That’s why each row has a different color: Mathematica sees this as a combination of six number line plots and gives each its own color by default. But don’t worry about the colors or the size and spacing of the dots; those can all be changed by passing options to NumberLinePlot. What you should worry about is how to turn flat list a into nested list b. Doing it by hand is both tedious and prone to error.

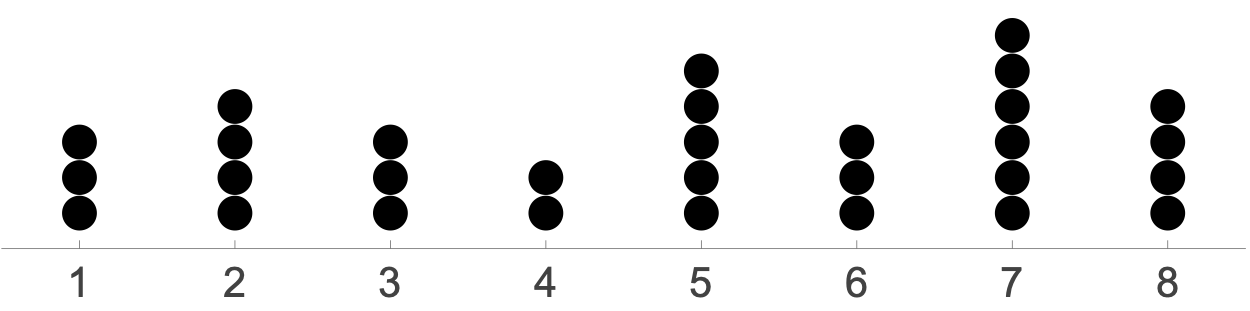

As it happens, someone has already worked that out and combined it with NumberLinePlot to make an external function, DotPlot, that makes the kind of graph we want. Running ResourceFunction["DotPlot"][a] produces

Again, we can add options to DotPlot to give it the style Wilkinson suggests. Calling it this way,

ResourceFunction["DotPlot"][a, Ticks -> {Range[8]},

AspectRatio -> .2, PlotRange -> {.5, 8.5},

PlotStyle -> Directive[Black, PointSize[.028]]]

gives us

After setting the aspect ratio to 1:5, I had to fiddle around with the PointSize to get the dots to sit on top of one another. It didn’t take long.

This is great, but I wanted to know what DotPlot was doing behind the scenes. So I downloaded its source notebook and poked around. The code wasn’t especially complicated, but there was one very clever piece. Let’s go through the steps.

First, we Sort the original flat list and Split it into a list of lists in which each sublist consists of a single repeated value.

nest = Split[Sort[a]]

yields

{{1, 1, 1}, {2, 2, 2, 2}, {3, 3, 3}, {4, 4}, {5, 5, 5, 5, 5},

{6, 6, 6}, {7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7}, {8, 8, 8, 8}}

Compare this with the nested list b we used above and you can see that they’re sort of opposites. If we think of these nested lists as matrices, the rows of b are the columns of nest, and vice versa. That suggests a Transpose of nest would get us to b, but the problem is that neither nest nor b are full matrices. They both have rows of different lengths.

The solution to this is a three-step process:

- Pad the rows of

nestwith dummy values so they’re all the same length. - Transpose that padded list of lists.

- Delete the dummy values from the transpose.

The code for the first step is

maxlen = Max[Map[Length, nest]];

padInnerLists[l_] := PadRight[l, maxlen, "x"]

padded = Map[padInnerLists, nest]

This sets maxlen to 6 and pads all of nest’s rows out to that length by adding x strings. The result is this value for padded:

{{1, 1, 1, "x", "x", "x"}, {2, 2, 2, 2, "x", "x"},

{3, 3, 3, "x", "x", "x"}, {4, 4, "x", "x", "x", "x"},

{5, 5, 5, 5, 5, "x"}, {6, 6, 6, "x", "x", "x"},

{7, 7, 7, 7, 7, 7}, {8, 8, 8, 8, "x", "x"}}

I should mention here that Map works the same way mapping functions work in other languages: it applies function to each element of a list and returns the list of results.

Now we can transpose it with

paddedT = Transpose[padded]

which yields

{{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8},

{1, 2, 3, "x", 5, 6, 7, 8}, {"x", 2, "x", "x", 5, "x", 7, 8},

{"x", "x", "x", "x", 5, "x", 7, "x"},

{"x", "x", "x", "x", "x", "x", 7, "x"}}

The last step is to use DeleteCases to get rid of the dummy values.

nestT = DeleteCases[paddedT, "x", All]

yields

{{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}, {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8},

{1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8}, {2, 5, 7, 8}, {5, 7}, {7}}

which is exactly what we want. This is what DotPlot does to prepare the original flat list for passing to NumberLinePlot.1

Now that I know how DotPlot works, I feel comfortable using it.

You may be wondering why I don’t just run

Histogram[a, {1}, Ticks -> {Range[8]}]

to get a histogram that presents basically the same information.

First, where’s the fun in that? Second, dot plots appeal to my sense of history. They have a kind of hand-drawn look that reminds me of using tally marks to count items in the days before we all used computers.

-

DotPlotuses anonymous functions and more compact notation than I’ve used here. But the effect is the same, and I wanted to avoid weird symbols like#,&, and/@. ↩

Baseball durations after the pitch clock

September 30, 2025 at 8:20 PM by Dr. Drang

A couple of years ago, after Major League Baseball announced they’d start using a pitch clock, I said I would write a post about the change in the duration of regular season games. I didn’t. My recent post about Apple’s Sports app and its misunderstanding of baseball standings reminded me of my broken promise. I decided to write a new game duration post after the 2025 season ended.

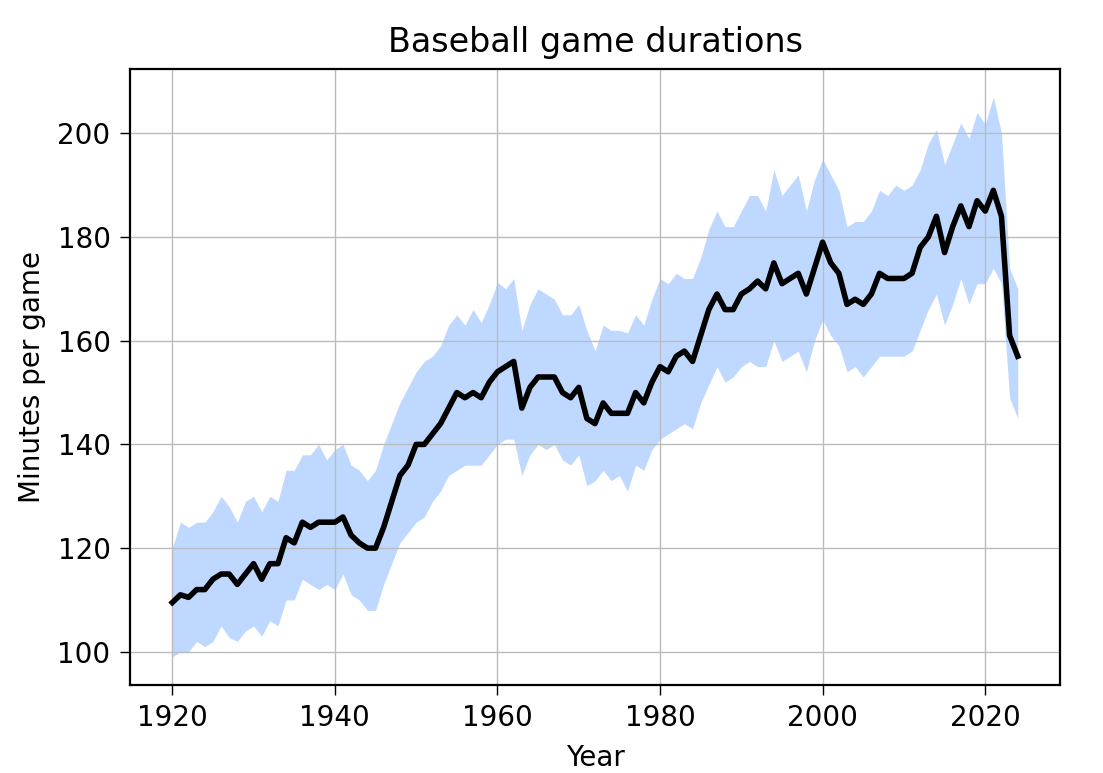

Unfortunately, Retrosheet, which is where I get my data, hasn’t published its 2025 game logs yet. I decided to go ahead with the post anyway, mainly because putting it off would probably lead to my forgetting again. So here’s the graph of regular season durations through the 2024 season. When the 2025 data comes in, I’ll update it (I hope).

The black line is the median duration, and the light blue zone behind it is the interquartile range. The middle 50% of games lie within that range.

Clearly, there was a huge dropoff in 2023, so I’d say the pitch clock was a big success. The further reduction in 2024 was within the historical year-to-year duration change—I wouldn’t attribute any significance to it.

Games are now roughly as long as they were in the early ’80s, so the powers at MLB have cut about four decades of fat from the game. And they did it without reducing the number of commercials, because they’d never do that.

I made the graph more or less the same way I made the last one, although I combined some of the steps into a single script. First, I downloaded and unzipped all the yearly game logs since 1920 from Retrosheet. They have names like gl1920.txt. Then I converted the line endings from DOS-style to Unix-style via

dos2unix gl*.txt

I got the dos2unix command from Homebrew.

I concatenated all the data into one big (189 MB) file using

cat gl*.txt > gl.csv

Although the files from Retrosheet have a .txt extension, they’re actually CSV files (albeit without a header line). That’s why I gave the resulting file a .csv extension.

I then ran the following script, which uses Python and Pandas to make a dataframe with just the columns I want from the big CSV file and calculate the quartile values for game durations on a year-by-year basis.

python:

1: #!/usr/bin/env python3

2:

3: import pandas as pd

4: from scipy.stats import scoreatpercentile

5: import sys

6:

7: # Make a simplified dataframe of all games with just the columns I want

8: cols = [0, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 18]

9: colnames = 'Date VTeam VLeague HTeam HLeague VScore HScore Time'.split()

10: df = pd.read_csv('gl.csv', usecols=cols, names=colnames, parse_dates=[0])

11:

12: # Add a column for the year

13: df['Year'] = df.Date.dt.year

14:

15: # Use the dataframe created above to make a new dataframe

16: # with the game duration quartiles for each year

17: cols = 'Year Q1 Median Q3'.split()

18: dfq = pd.DataFrame(columns=cols)

19: for y in df.Year.unique():

20: p25 = scoreatpercentile(df.Time[df.Year==y], 25)

21: p50 = scoreatpercentile(df.Time[df.Year==y], 50)

22: p75 = scoreatpercentile(df.Time[df.Year==y], 75)

23: dfq.loc[y] = [y, p25, p50, p75]

24:

25: # Write a CSV file for the yearly duration quartiles

26: dfq.Year = dfq.Year.astype('int32')

27: dfq.to_csv('gametimes.csv', index=False)

This code is very similar to what I used a couple of years ago. You can read that post if you want an explanation of any of the details.

Now I had a new CSV file, called gametimes.csv, that looked like this

Year,Q1,Median,Q3

1920,99.0,109.5,120.0

1921,100.0,111.0,125.0

1922,100.0,110.5,124.0

1923,102.0,112.0,125.0

1924,101.0,112.0,125.0

1925,102.0,114.0,127.0

[and so on]

The graph was made by running this script, which reads the data from gametimes.csv and uses Matplotlib to output the PNG image shown above:

python:

1: #!/usr/bin/env python3

2:

3: import pandas as pd

4: import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

5: from datetime import date

6:

7: # Import game time data

8: df = pd.read_csv('gametimes.csv')

9:

10: # Create the plot with a given size in inches

11: fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

12:

13: # Add the interquartile range and the median

14: plt.fill_between(df.Year, df.Q1, df.Q3, alpha=.25, linewidth=0, color='#0066ff')

15: ax.plot(df.Year, df.Median, '-', color='black', lw=2)

16:

17: # Gridlines and ticks

18: ax.grid(linewidth=.5, axis='x', which='major', color='#bbbbbb', linestyle='-')

19: ax.grid(linewidth=.5, axis='y', which='major', color='#bbbbbb', linestyle='-')

20: ax.tick_params(which='both', width=.5)

21:

22: # Title and axis labels

23: plt.title('Baseball game durations')

24: plt.xlabel('Year')

25: plt.ylabel('Minutes per game')

26:

27: # Save as PNG

28: day = date.today()

29: dstring = f'{day.year:4d}{day.month:02d}{day.day:02d}'

30: plt.savefig(f'{dstring}-Baseball game durations.png', format='png', dpi=200)

I don’t know when the folks at Retrosheet will add the 2025 data. Maybe after the World Series. I’ll check back then and update the post if there’s a new year of game logs.