Axial vs. bending stiffness

December 19, 2025 at 12:02 PM by Dr. Drang

At the end of yesterday’s post, I mentioned that axial deformations in framework members are typically two orders of magnitude less than the lateral (bending) deformations. It’s easy to see why.

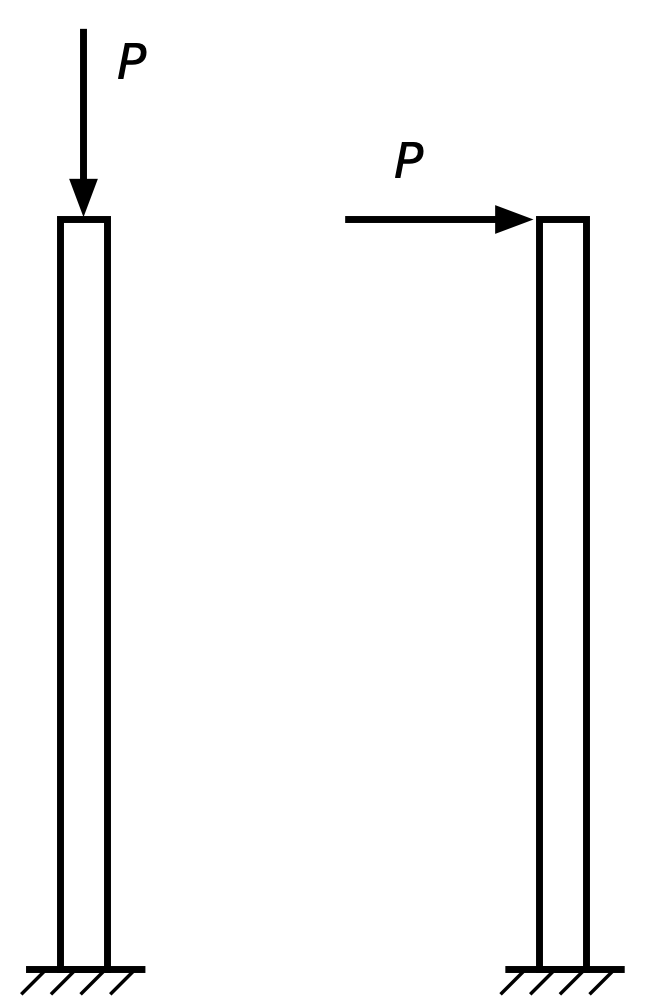

Consider a column with length , cross-sectional area , and moment of inertia . We’ll calculate the tip deflection of this column under two loads of the same magnitude, : an axial compression load and a horizontal load to the right.

Under the compression load, the tip of the column will move down by

Under the horizontal load, the tip will move to the right by

The ratio of lateral deflection to axial deflection is therefore

When calculating buckling loads of columns, it’s often useful to consider the radius of gyration, , which is defined this way:

We’re not doing a buckling calculation here, but we can use the radius of gyration to help us get a sense of the deflection ratio, which we can rewrite as

The radius of gyration is some fraction of a characteristic dimension of the cross-section. For example, if the cross-section is a square with side length , the area is and the moment of inertia is , so

In typical structures, the stick-like members—beams, columns, braces, etc.—tend to be long and thin, with aspect ratios of about 10. The deflection ratio is roughly the square of the aspect ratio, so lateral deflections are typically two orders of magnitude greater than axial deflections. That’s why it’s common to ignore the axial deflections in analyses like yesterday’s.

This doesn’t mean axial deflections can always be ignored. In tall buildings, the columns carry the weight of all the floors above them, and column shortening has to be accounted for, especially in the lower floors. Also, when using modern numerical techniques for structural analysis, there’s basically no extra work involved in calculating the axial deflections along with the bending deflections, so the axial deflections pop out of the computer as a matter of course.

Frame sidesway again

December 18, 2025 at 11:38 AM by Dr. Drang

I’ve been meaning to follow up on the “sense of structure” post I wrote just after Thanksgiving. I don’t have anything profound to say, but I did want to give complete solutions for both the off-center vertical load problem and the horizontal load problem.

First, though, I want to mention a nice email conversation I had with Karl Hoitsma, proprietor of the Mathpax blog. He pointed me to this post of his from a few years ago in which he describes being asked essentially the same frame sidesway question I was. The only real differences were that his oral exam was about five years after mine and that he was at Texas A&M instead of U of I. Oh, and he hadn’t been prepped for the question.

In that post, Karl gives a few solutions to the problem, which I found fun to go through. I had already solved the horizontal load problem for a simpler frame, and it was interesting to compare our approaches to the problem. As I’ve been trying to get better at Mathematica, I decided to do the off-center load problem and redo the horizontal load problem using the Wolfram Language. I won’t go through the code here, just the results.

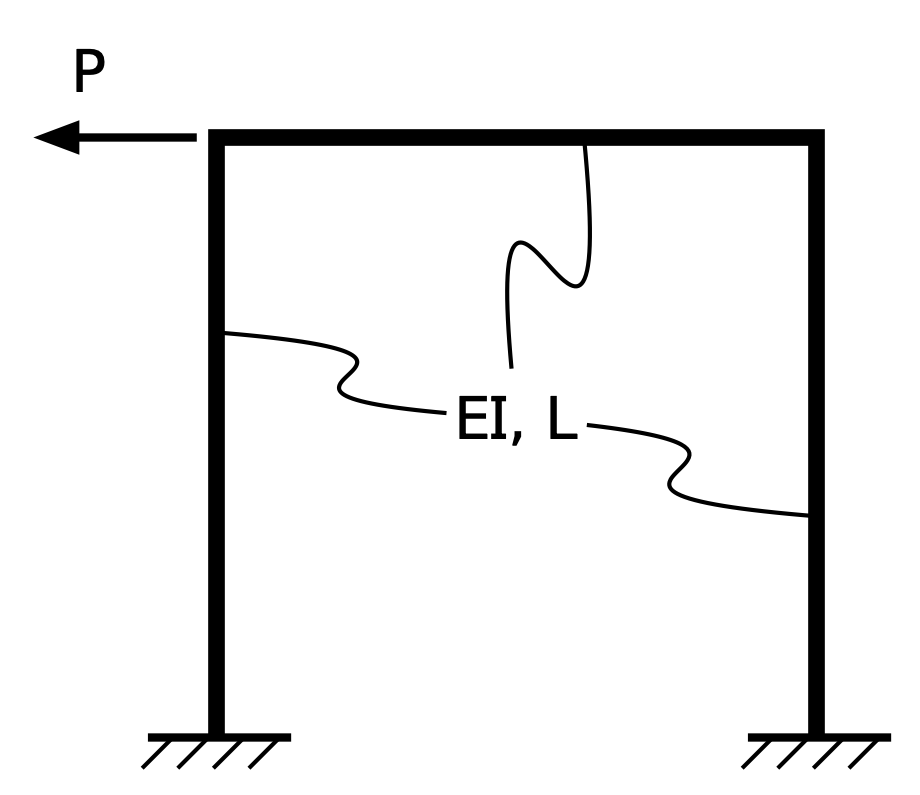

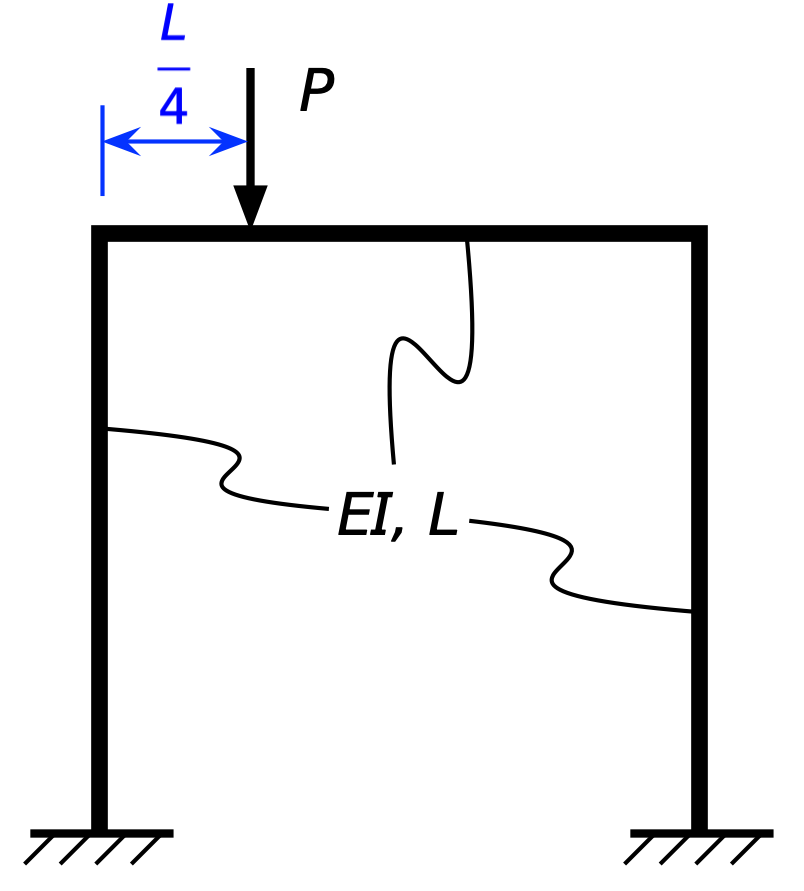

Let’s start with the simpler problem: a portal frame with fixed column bases in which the beam and columns are identical in both cross-section and length.

is the modulus of elasticity of the material, and is the moment of inertia of the cross-section.1

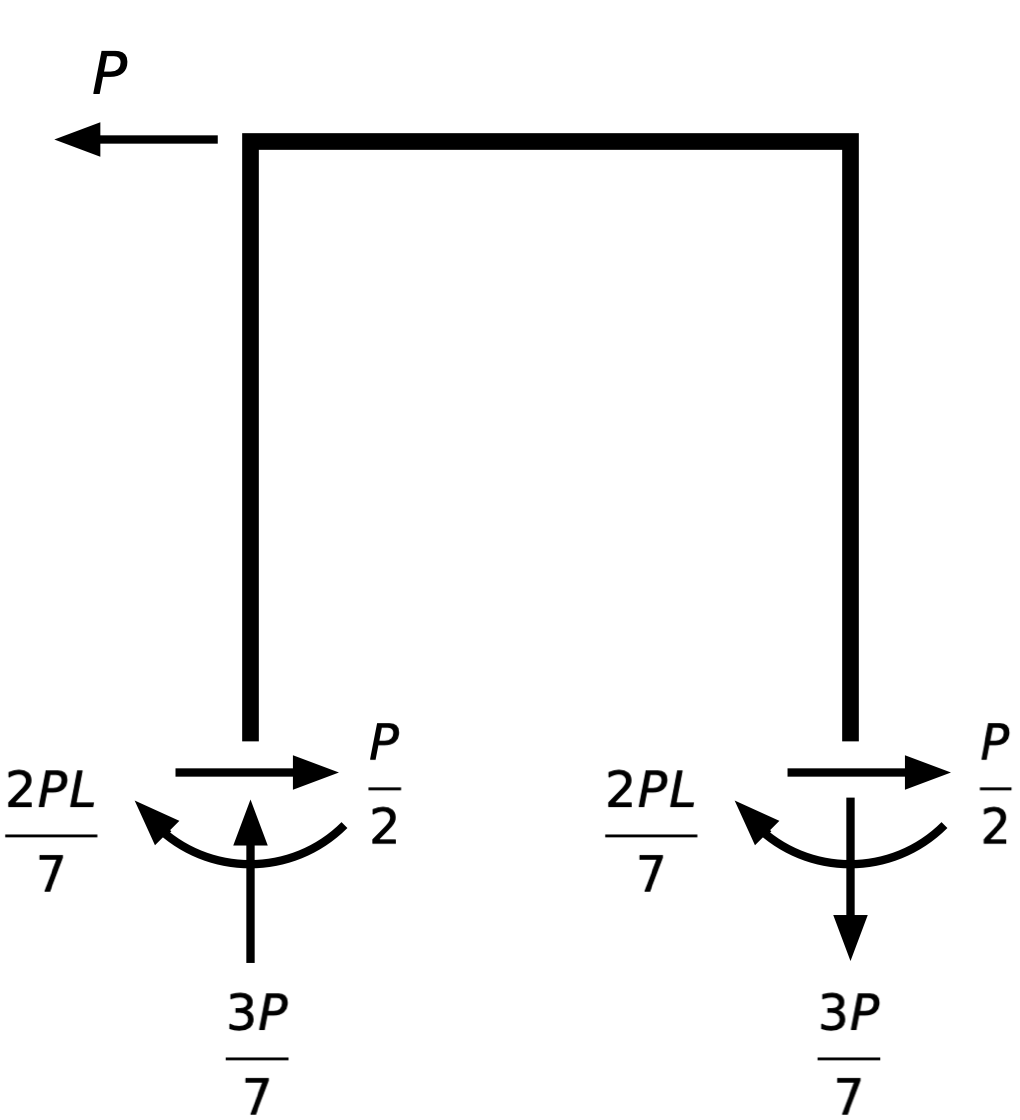

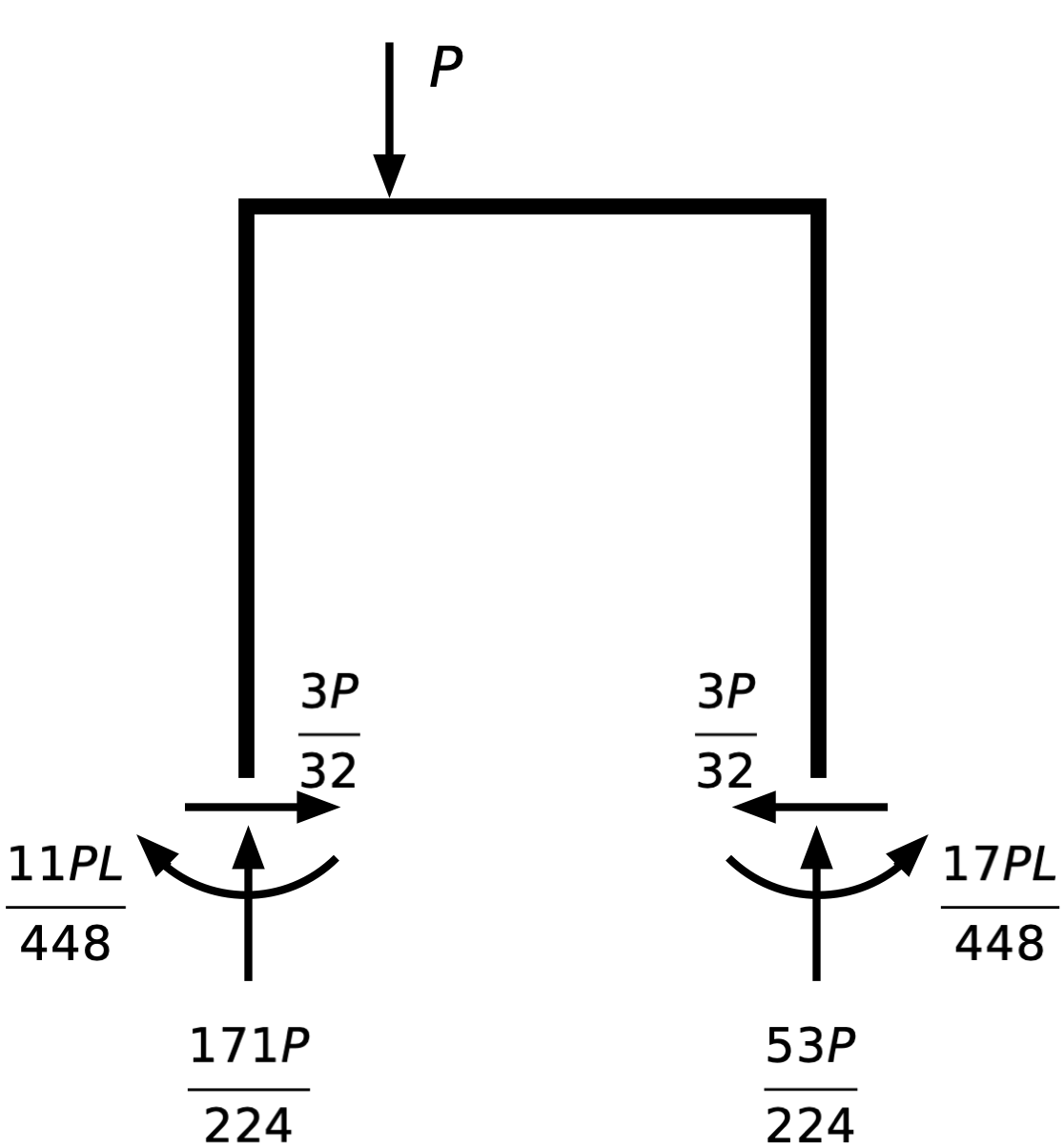

This is a statically indeterminate system. You cannot determine the reactions at the bases of the columns through statics alone; you have to account for the stiffnesses of the members. But once you’ve done that, the reactions are these:

It’s a decent exercise to confirm that these reactions are in equilibrium. It should be immediately obvious that the horizontal and vertical forces are in balance. It takes only a little more effort to show that the clockwise and counter-clockwise moments about any point are also in balance. (As a practical matter, I’d choose the base of one of the columns to take moments about, as that eliminates three of the forces from the equation.)

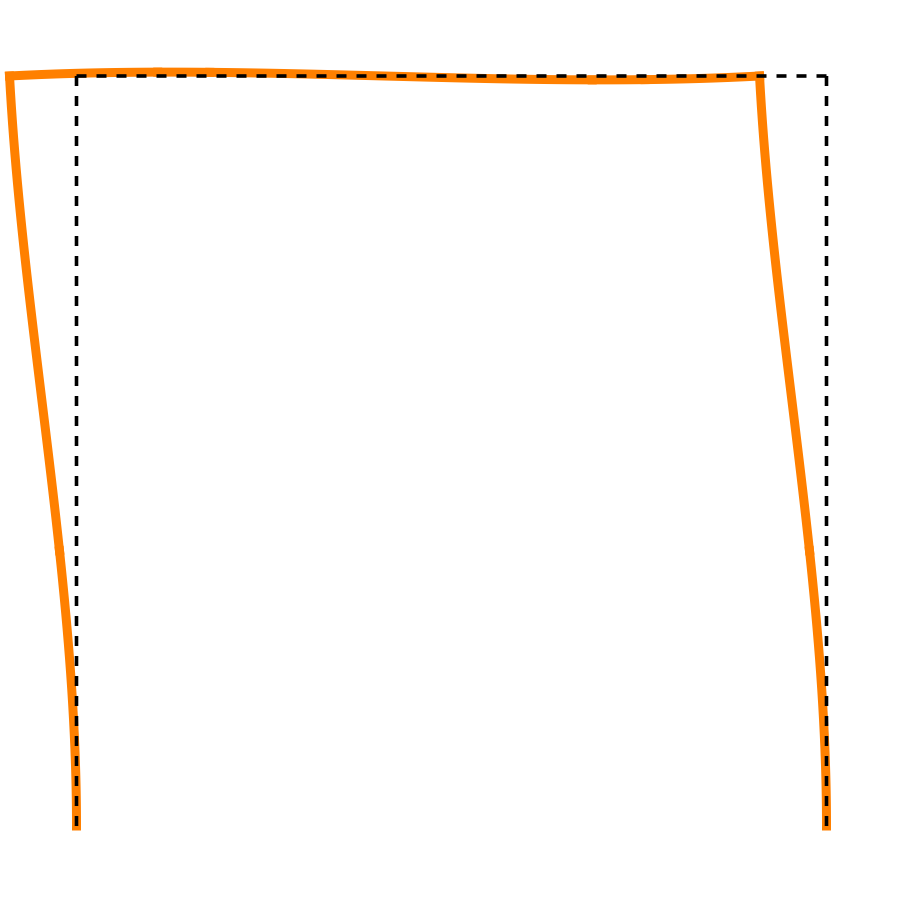

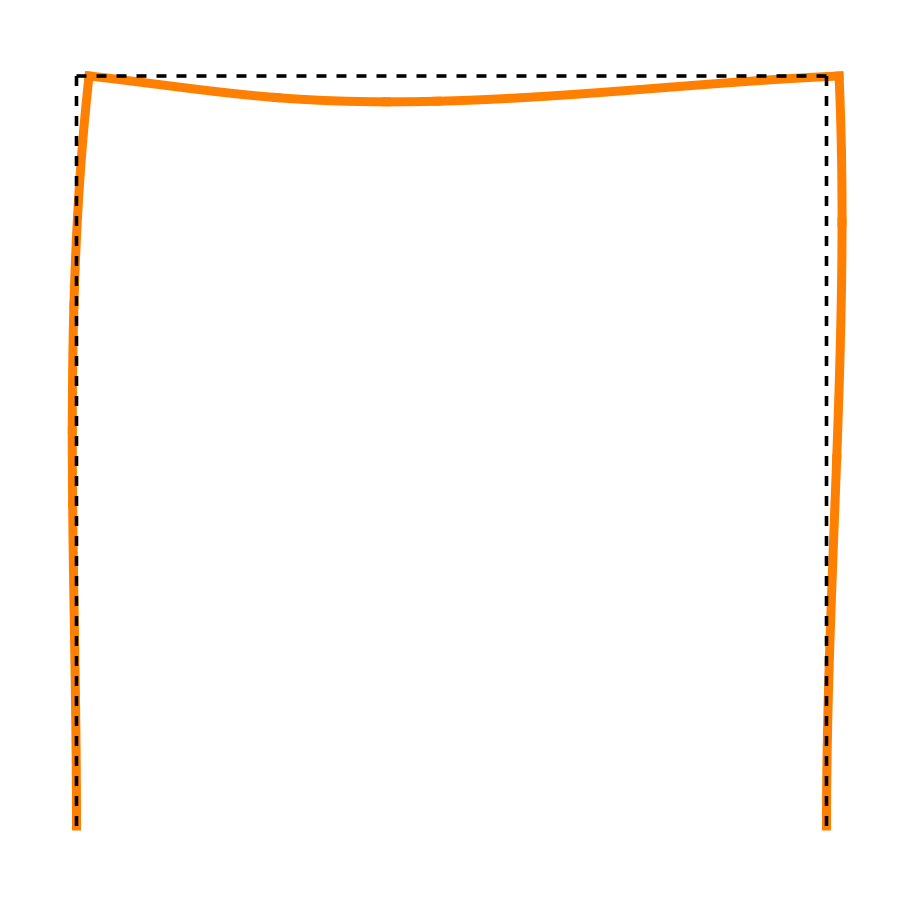

What I really wanted to show was the deflected shape of the frame under this loading. If you recall from that earlier post, I drew a deflected shape in which the left half of the beam goes up and the right half goes down. Knowing this was key to using reciprocity to determine which way the frame sways when it’s subjected to an off-center vertical load. Here’s the deflected shape plotted from a formal solution instead of just drawn on the basis of my sense of the structure’s behavior:

The leftward displacement at the top of each column is

and the counter-clockwise rotation at the top of each column is

It’s the CCW rotation that lifts the left half of the beam upward and pushes the right half downward. As you can see, though, the vertical deflection of the beam is pretty small compared to the horizontal deflection of the columns.

A note on units: In these equations, has units of force, has units of length, has units of force per length squared, and has units of length to the fourth power. So has units of length, as expected, and is a pure number, which means we’re getting the rotation in radians.

OK, now let’s look at the frame with a downward off-center load:

I’ve put the load at the quarter point of the beam for convenience, but it doesn’t matter where it is as long as it’s to the left of the centerline. Here are the reactions:

Again, you can confirm that these forces and moments are in equilibrium. Here’s the deflected shape:

For this loading, the leftward displacement at the top of each column is

The minus sign means the displacement is actually to the right, which matches what we figured out a few weeks ago. Now we have the magnitude in addition to the direction.

As I said above, I don’t want to go through the details of the code that got me to these answers, but if you’re interested, you can see it using the following Wolfram Cloud links:

I should mention that in both of these analyses I’m ignoring the axial deformation of the members. This is a common practice in frame analysis, as axial deformations are typically about two orders of magnitude less than lateral deformations. Leaving out the axial terms cuts out a lot of complexity in symbolic solutions like this while retaining good accuracy.

-

In physics class, you used a different moment of inertia when you were learning about rotating bodies. Strictly speaking, the in this problem should be called the second moment of area, but structural engineers always call it the moment of inertia. It’s a reasonable reuse of the phrase, as the second moment of area is a measure of the resistance of a cross-section to rotation as a structural member is bent. ↩

Be careful where you click

December 11, 2025 at 10:24 AM by Dr. Drang

I ran into an example of especially bad design on a web page yesterday. Not “how it looks” design; “how it works” design.

Here’s an excerpt from an online payment page:

Looks straightforward, right? Just click in the field, type in the amount to pay, and off you go. But unlike almost every other example you’ll see nowadays, this field doesn’t automatically select its dummy contents when you click in it. So what you type does not replace the dummy contents. Here’s a video showing what can happen.

There are three interactions in the video.

- I clicked to the right of the “$0.00” default amount and typed “12345.” You can see the zeros disappear as I type, and the amount at the end is $123.45. Let’s assume this is what I wanted to enter.

- I clicked just to the right of the decimal point and typed “12345.” The cursor first jumps to the beginning of the amount. After I type the “1,” it jumps to the end, and the “2345” fills in from the right. But two of the zeros never disappear, and the amount at the end is $10,023.45.

- I clicked just to the right of the dollar sign and typed “12345.” After I type “123,” the cursor jumps to the end and the “45” fills in from the right. None of the zeros disappear, and the amount at the end is $123,000.45.

I want to emphasize that I never moved the cursor myself after the initial click in the field. All I did was type.

As you might guess, I discovered this when I nearly made an enormous overpayment.

It’s true that a standard HTML <input type="text" /> form field with a value attribute will put the cursor where you click, so a user could screw up the entry in that kind of field, too. But the value attribute is meant to be a default, a common legitimate entry. No one ever goes online to pay $0.00. A more appropriate pure HTML solution would be to use the placeholder attribute, which puts gray text in the field to suggest what the field is for. As soon as you start typing in such a field, the placeholder text disappears.

For the designers of this website, though, standard HTML just wasn’t good enough. They wanted to show off their elite JavaScript skills to keep the dollar sign and decimal point in place and add commas as the user types. In the process, they created a field in which the cursor jumps around haphazardly and the user can easily create a mistaken payment.

Am I the only user who’s noticed this? Impossible.1 But we’ve gotten so used to crap like this that we just sigh, figure out how to fix things on our end, and move on with our lives. I did point this problem out to the vendor, who was surprised to hear it, but payment processing is a service they buy from someone else. It’s unlikely that the people responsible for the poor user interface will ever be told to fix it.

-

I probably am the only person who tried out all the different places to click. Not included in the video: clicking just to the left of the decimal point, which works the same as clicking just to right of it; and clicking between the zeros after the decimal point, which leads to an entry of $1,023.45 ↩

Equation of time

December 9, 2025 at 9:01 PM by Dr. Drang

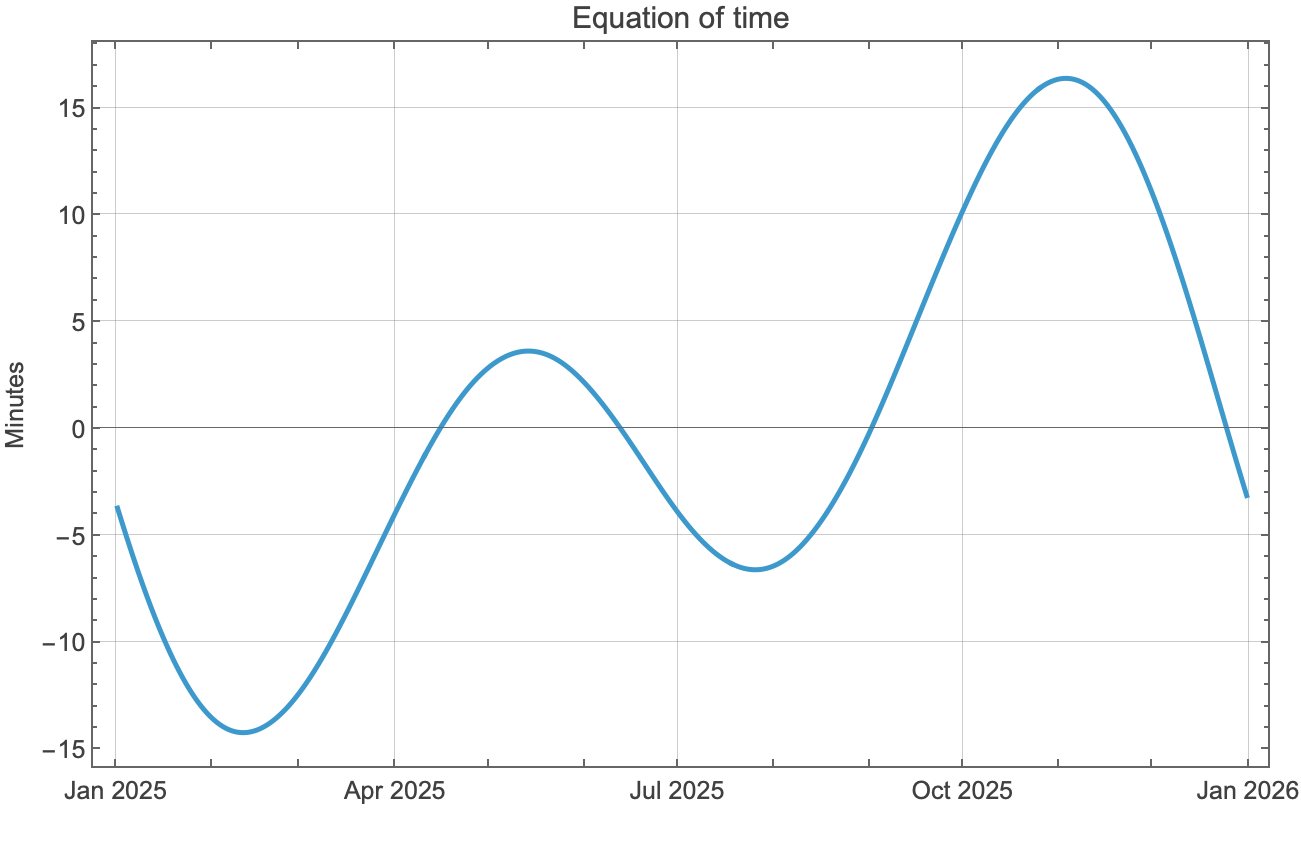

Speaking of the equation of time, which I was in yesterday’s post, I wanted to extend some of the work I did in that post to draw my own EoT plot and to be able to adjust it to show the difference between solar time and standard time anywhere on Earth.

In Mathematica, solar time is best tackled with the SunPosition function.1 This function can be called in a variety of ways. We’ll focus initially on getting the Sun’s position at noon at a point on the Prime Meridian, and we want the position given as the right ascension and declination. These are equatorial coordinates on the celestial sphere. Because we’re doing time calculations, only the right ascension—which is the longitudinal coordinate—matters to us. Luckily, right ascension is given not in degrees, but in time units: hours, minutes, and seconds. This is a useful unit in astronomy because the difference in right ascension between two celestial objects is the time gap between their passage over the observer’s local meridian. You can find a good explanation of celestial coordinates at Sky & Telescope.

For standard time, we have to be a little careful. Since we’re measuring the Sun in terms of right ascension, we should do the same for standard time. That means getting the sidereal time of the location on Earth, which is the right ascension of the local meridian for a given time.

In simplest terms, we have two right ascensions, one for the Sun’s position and one for the sidereal time. We take their difference to get the equation of time. Unfortunately, there’s a practical complication that messes up this seemingly simple calculation. Right ascension is never greater than 24 hours—it wraps around back around to zero. So we can have right ascension values that are close to one another but don’t seem to be close at all. For example 23:57:00 and 00:2:30 are only 5½ minutes apart, but you get -23:54:30 if you subtract the first from the second. We have to manipulate the right ascension values before subtraction to make sure we get the correct difference.

The standard equation of time graph you’ll see on websites and in textbooks is plotted for a point on the Prime Meridian using UTC. Here’s what it looks like:

It’s plotted so that positive values represent periods for which the solar time is ahead of standard time, e.g. solar noon, when the Sun is at its highest point, comes before 12:00:00 UTC. Here’s the Mathematica notebook that produced the plot:

Some comments:

- The latitude of the point on the Prime Meridian doesn’t matter. I chose 51.5° because that’s about the latitude of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

- I chose local noon for the time at which to get the

SunPositionandSiderealTime. The pure function used in theMapcall to generate the list of Sun positions extracts only the first (right ascension) term of the position. - The initial plots of

sunposandstimeshow the wraparounds, or jumps, in right ascension as it exceeds 24 hours. The expressions forsunjumpandtimejumpreturn the lists, in reverse order, of the indices at which the jumps occur. The expressions are more complicated than they need to be for this particular problem because I wanted them to be able to handle longer date ranges in which there will be more than just one jump. - The two

Doloops—an expression I thought I’d given up when I stopped using Fortran—adjustsunposandstimeto get rid of the jumps. They, too, are built to handle longer date ranges with more jumps. The third graph showssunposandstimeafter the adjustments. - The difference between

sunposandstimecan now be calculated with a simple subtraction. The values are converted from hours to minutes because that’s a more convenient unit. The subtraction is done asstime - sunposbecause that means we’ll get positive numbers when the Sun is ahead (west) of the Prime Meridian and negative numbers when the Sun is behind (east) of the Prime Meridian.

You may recall from yesterday’s post that I said solar noon was currently about 15 minutes ahead of standard noon in Naperville, Illinois, where I live. That doesn’t match up with the equation of time because Naperville isn’t on the Prime Meridian, nor is it on the 90° W meridian, which would match up perfectly with the local UTC-6 timezone. I wanted to make an adjusted equation of time plot to account for that. Also, I wanted winter to be at the center of the graph, not split between the left and right edges.

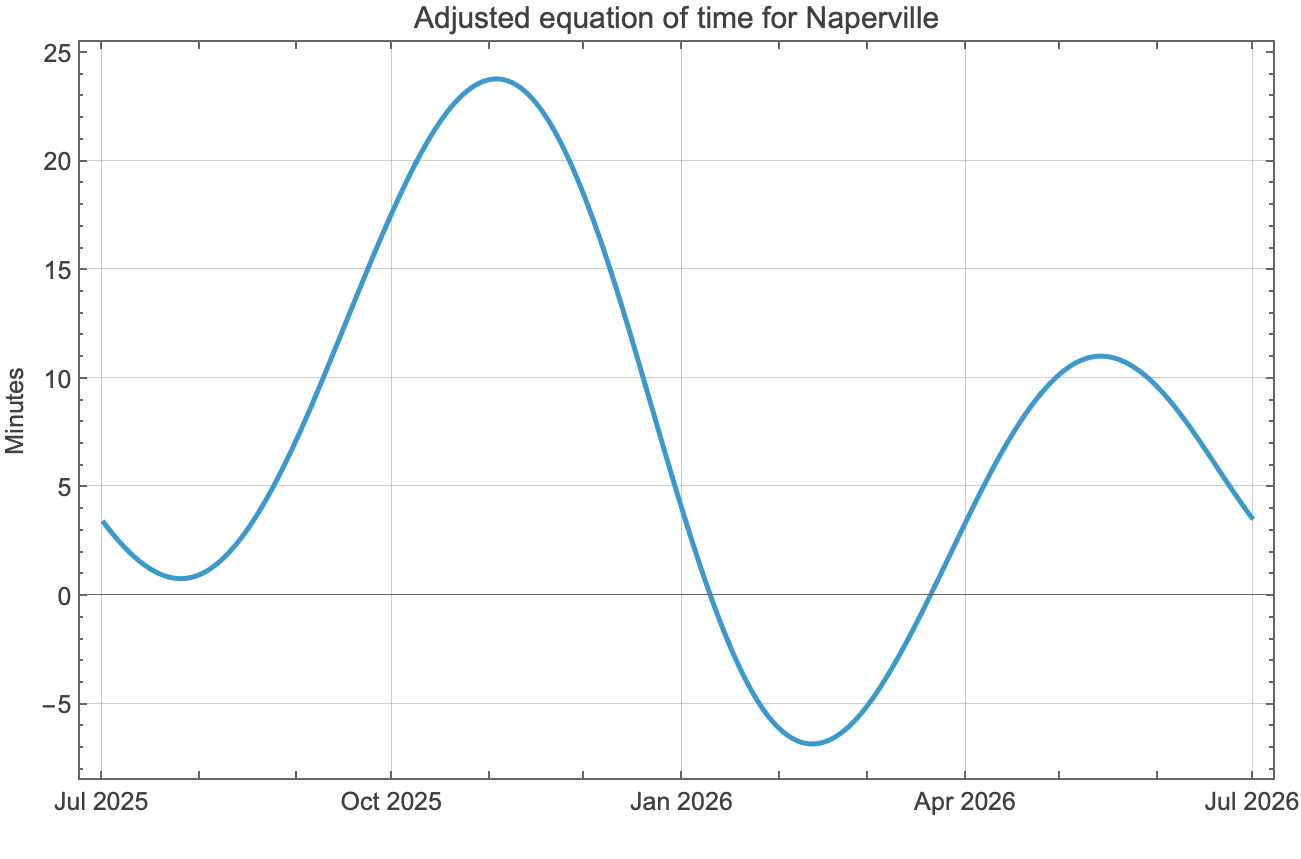

Here’s the adjusted graph:

Apart from the six-month sideways shift, the graph is pushed up because Naperville is about 1.85° east of the 90° W meridian. With a four-minute difference for every degree, that means the whole graph is about minutes higher than standard equation of time.

Here’s the notebook that made the graph:

The changes are all at the top of the notebook: different coordinates for the location, different start and end dates, and a different timezone. But the rest of the notebook is the same as before.

-

In the Applications section of the

SolarPositiondocumentation, there’s an example calculation and graph of the equation of time, but I don’t like it. The calculations it goes through are both hard to follow and can’t be applied to locations off the Prime Meridian. ↩