On the average

January 26, 2026 at 8:42 AM by Dr. Drang

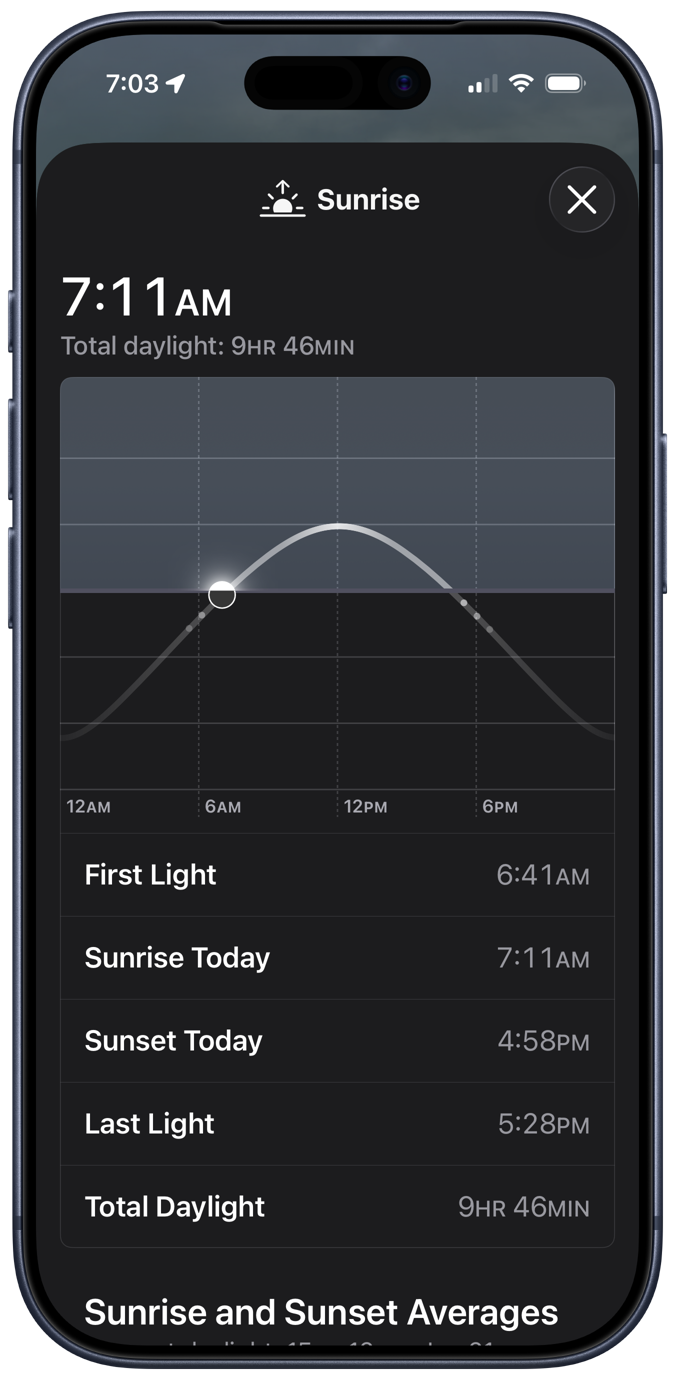

A few days ago, I was poking around in Apple’s Weather app and came across some interesting stuff hiding behind the sunrise/sunset box. First, there’s a plot that shows the movement of the sun throughout the day, followed by sunrise and sunset times:

The little dots under the “horizon” represent the beginnings and endings of civil, nautical, and astronomical twilight, which is a nice addition to the plot. I assume the vertical axis has something to do with the Sun’s altitude angle, but since the plot gives no units, it must be an example of Bezos astronomy.

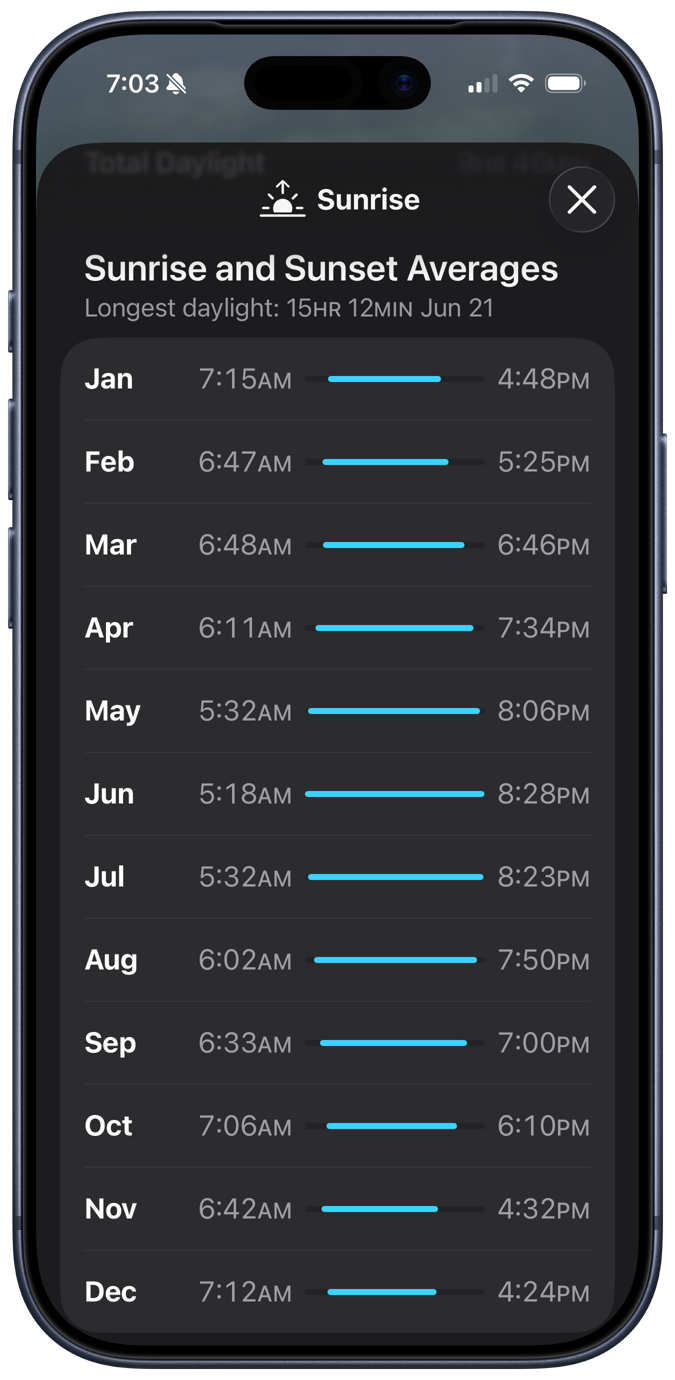

Scrolling down, we come to this odd graphic: the average sunrise and sunset times for each month of the year.

Given that I live in a state that switches between Standard Time and Daylight Saving Time, this is a troubling calculation. There’s no trouble making the calculation, of course: you just add up all the sunrise or sunset times and divide by the number of days in the month. And that’s clearly what Apple’s done. No, the trouble comes in March and November, the months when we switch from CST to CDT and back. What is the meaning of “average” when the individual values are measured differently?

On the second Sunday in March, sunrise and sunset suddenly become an hour later than they were, and the same thing happens in reverse on the first Sunday in November. Here in 2026, those days will be March 8 and November 1; in 2027, they’ll be March 14 and November 7. That the number of days we’re on CDT and CST in March and November changes from year to year makes the “averages” for those months even weirder.

After thinking about this for a while, I came to three conclusions:

- It’s nice to have on hand a simple display of how sunrise and sunset change over the course of a year.

- I may be the only person bothered by the way Apple presents this information.

- I’ve already shown how I’d like to see it done.

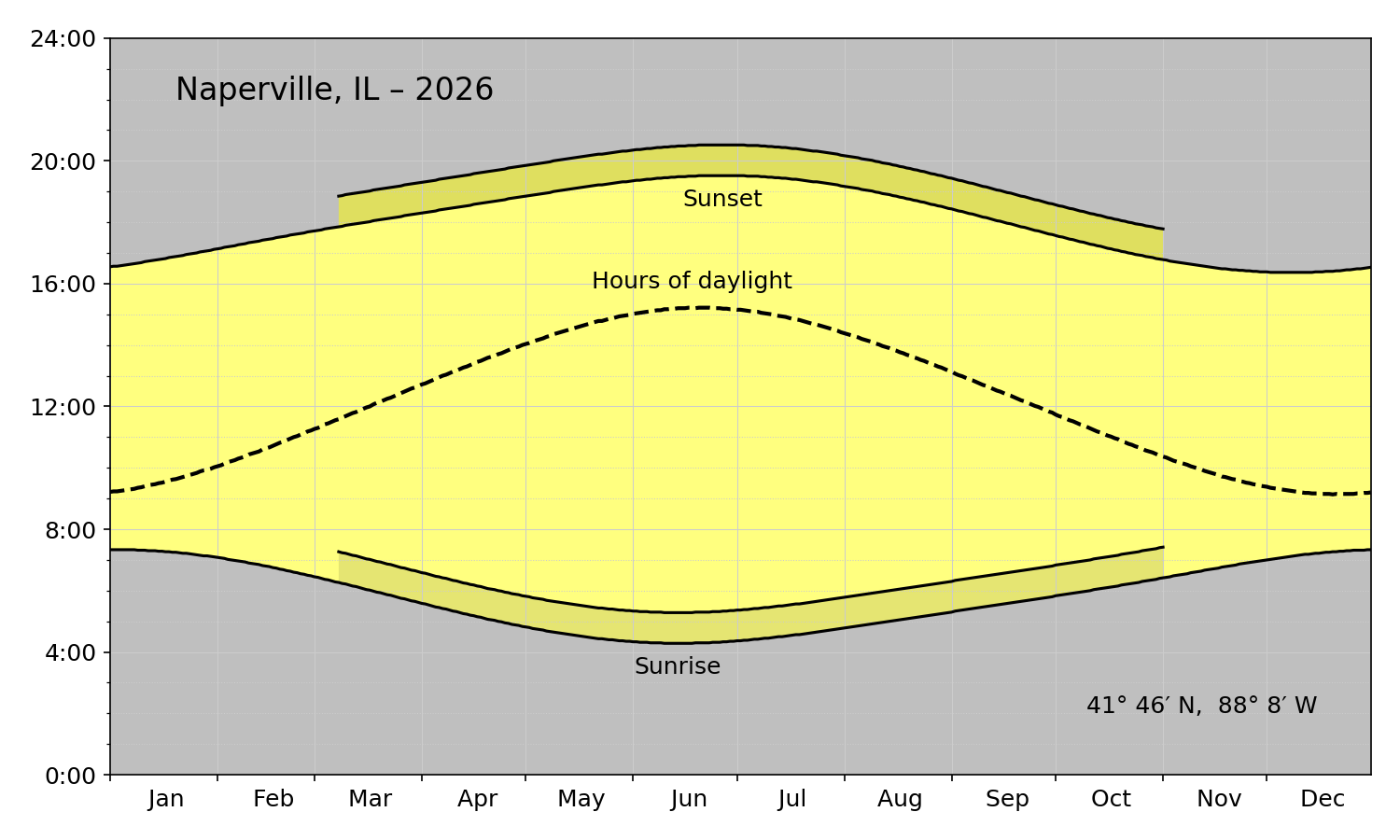

A couple of years ago, I wrote a Python script that used Matplotlib and data from the US Naval Observatory to generate plots like this:

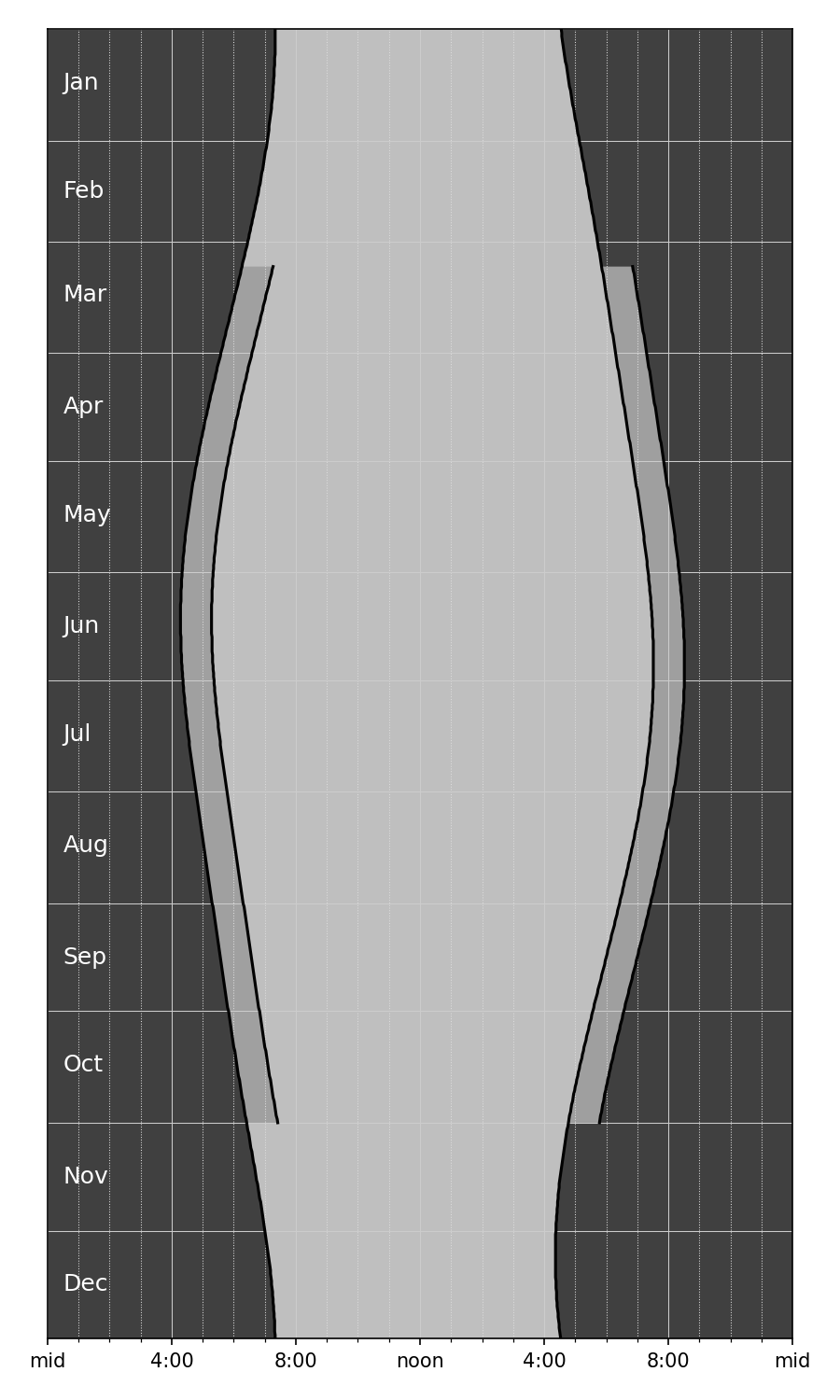

A graph like this wouldn’t work well on a phone because it’s wide instead of tall. But I figured it wouldn’t be too hard to redo it with the axes switched to give it a portrait format. I removed the various annotations because the location would be given in the Weather app. I also removed the “Hours of daylight” curve; without a 24-hour clock, I couldn’t cheat and treat the horizontal axis as both a time and a duration. I also got rid of the yellow and put everything in shades of gray to better match Apple’s aesthetic.

Apple would never include a plot with this many gridlines, but I couldn’t bring myself to get rid of them. They really help you track how the sunrise and sunsets change over the course of the year. Apple doesn’t want to scare its customers with complexity; when it feels the need to show detail, it puts it in a popup that appears when you tap inside the plot. Apple’s way is certainly cleaner looking, but I prefer seeing all the information at once.

Here’s the code that produced the plot above:

python:

1: #!/usr/bin/env python3

2:

3: import sys

4: import re

5: from dateutil.parser import parse

6: from datetime import datetime

7: from datetime import timedelta

8: from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

9: import matplotlib.dates as mdates

10: from matplotlib.ticker import MultipleLocator, FormatStrFormatter

11:

12:

13: # Functions

14:

15: def headerInfo(header):

16: "Return location name, coordinates, and year from the USNO header lines."

17:

18: # Get the place name from the middle of the top line

19: left = 'o , o ,'

20: right = 'Astronomical Applications Dept.'

21: placeName = re.search(rf'{left}(.+){right}', header[0]).group(1).strip()

22:

23: # If the place name ends with a comma, a space, and a pair of capitals,

24: # assume it's in location, ST format and capitalize the location while

25: # keeping the state as all uppercase. Otherwise, capitalize all the words.

26: if re.match(r', [A-Z][A-Z]', placeName[-4:]):

27: placeParts = placeName.split(', ')

28: location = ', '.join(placeParts[:-1]).title()

29: state = placeParts[-1]

30: placeName = f'{location}, {state}'

31: else:

32: placeName = placeName.title()

33:

34: # The year is at a specific spot on the second line

35: year = int(header[1][80:84])

36:

37: # The latitude and longitude are at specific spots on the second line

38: longString = header[1][10:17]

39: latString = header[1][19:25]

40:

41: # Reformat the latitude into d° m′ N format (could be S)

42: dir = latString[0]

43: degree, minute = latString[1:].split()

44: lat = f'{int(degree)}° {int(minute)}′ {dir}'

45:

46: # Reformat the longitude into d° m′ W format

47: dir = longString[0]

48: degree, minute = longString[1:].split()

49: long = f'{int(degree)}° {int(minute)}′ {dir}'

50:

51: return placeName, lat, long, year

52:

53: def bodyInfo(body, isLeap):

54: "Return lists of sunrise, sunset, and daylight length hours from the USNO body lines."

55:

56: # Initialize

57: sunrises = []

58: sunsets = []

59: lengths = []

60:

61: # Rise and set character start positions for each month

62: risePos = [ 4 + 11*i for i in range(12) ]

63: setPos = [ 9 + 11*i for i in range(12) ]

64:

65: # Collect data from each day

66: for m in range(12):

67: for d in range(daysInMonth[m]):

68: riseString = body[d][risePos[m]:risePos[m]+4]

69: hour, minute = int(riseString[:2]), int(riseString[-2:])

70: sunrise = hour + minute/60

71: setString = body[d][setPos[m]:setPos[m]+4]

72: hour, minute = int(setString[:2]), int(setString[-2:])

73: sunset = hour + minute/60

74: sunrises.append(sunrise)

75: sunsets.append(sunset)

76: lengths.append(sunset - sunrise)

77:

78: return(sunrises, sunsets, lengths)

79:

80: def dstBounds(year):

81: "Return the DST start and end day indices according to current US rules."

82:

83: # Start DST on second Sunday of March

84: d = 8

85: while datetime.weekday(dstStart := datetime(year, 3, d)) != 6:

86: d += 1

87: dstStart = (dstStart - datetime(year, 1, 1)).days

88:

89: # End DST on first Sunday of November

90: d = 1

91: while datetime.weekday(dstEnd := datetime(year, 11, d)) != 6:

92: d += 1

93: dstEnd = (dstEnd - datetime(year, 1, 1)).days

94:

95: return dstStart, dstEnd

96:

97:

98: # Start processing

99:

100: # Read the USNO data from stdin into a list of lines.

101: # Text should come from https://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/RS_OneYear

102: usno = sys.stdin.readlines()

103:

104: # Get location and year from header

105: placeName, lat, long, year = headerInfo(usno[:2])

106:

107: # Month information, adjusted for leap year if needed.

108: monthNames = 'Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec'.split()

109: isLeap = (year % 400 == 0) or ((year % 4 == 0) and not (year % 100 == 0))

110: if isLeap:

111: daysInMonth = [31, 29, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31]

112: else:

113: daysInMonth = [31, 28, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31]

114:

115: # Get sunrise, sunset, and sunlight length lists from body

116: sunrises, sunsets, lengths = bodyInfo(usno[9:], isLeap)

117:

118: # Generate list of days for the year

119: currentDay = datetime(year, 1, 1)

120: lastDay = datetime(year, 12, 31)

121: days = [currentDay]

122: while (currentDay := currentDay + timedelta(days=1)) <= lastDay:

123: days.append(currentDay)

124:

125: # The portion of the year that uses DST

126: dstStart, dstEnd = dstBounds(year)

127: dstDays = days[dstStart:dstEnd + 1]

128: dstRises = [ x + 1 for x in sunrises[dstStart:dstEnd + 1] ]

129: dstSets = [ x + 1 for x in sunsets[dstStart:dstEnd + 1] ]

130:

131: # Plot the data

132: fig, ax =plt.subplots(figsize=(6,10))

133:

134: # Shaded areas

135: plt.fill_betweenx(days, sunrises, sunsets, facecolor='gray', alpha=.5)

136: plt.fill_betweenx(days, 0, sunrises, facecolor='black', alpha=.75)

137: plt.fill_betweenx(days, sunsets, 24, facecolor='black', alpha=.75)

138: plt.fill_betweenx(dstDays, sunsets[dstStart:dstEnd + 1], dstSets, facecolor='white', alpha=.5)

139: plt.fill_betweenx(dstDays, sunrises[dstStart:dstEnd + 1], dstRises, facecolor='black', alpha=.16)

140:

141: # Curves

142: plt.plot(sunrises, days, color='k')

143: plt.plot(sunsets, days, color='k')

144: plt.plot(dstRises, dstDays, color='k')

145: plt.plot(dstSets, dstDays, color='k')

146:

147: # Background grids

148: ax.grid(which='major', color='#ccc', ls='-', lw=.5)

149: ax.grid(which='minor', color='#ddd', ls=':', lw=.5)

150:

151: # Vertical axis grid at month boundaries

152: # ax.tick_params(axis='both', which='major', labelsize=12)

153: plt.ylim(datetime(year, 1, 1), datetime(year, 12, 31))

154: plt.tick_params(axis='y', length=0)

155: m = mdates.MonthLocator(bymonthday=1)

156: mfmt = mdates.DateFormatter('')

157: ax.yaxis.set_major_locator(m)

158: ax.yaxis.set_major_formatter(mfmt)

159: ax.yaxis.set_inverted(True)

160:

161: # Month labels inside the plot in white letters

162: for m in range(12):

163: middle = sum(daysInMonth[:m]) + daysInMonth[m]//2

164: ax.text(.5, days[middle], monthNames[m], fontsize=12, color='w', ha='left', va='center')

165:

166: # Horizontal axis labels formatted like h:mm

167: plt.xlim(0, 24)

168: xmajor = MultipleLocator(4)

169: xminor = MultipleLocator(1)

170: ax.xaxis.set_major_locator(xmajor)

171: ax.xaxis.set_minor_locator(xminor)

172: plt.xticks(ticks=[0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24], labels=['mid', '4:00', '8:00', 'noon', '4:00', '8:00', 'mid'])

173:

174: # Tighten up the white border and save

175: fig.set_tight_layout({'pad': 1.5})

176: plt.savefig(f'{placeName}-{year}.png', format='png', dpi=150)

It’s a modification of the script given in my post from a couple of years ago. The main difference, apart from the color changes, is that instead of using Matplotlib’s fill_between function, I used the similar fill_betweenx function in Lines 135–139. Because the axes were switched, I needed to fill between vertical curves instead of horizontal curves.

The other unusual thing I did was use Matplotlib’s text function in Lines 161–164 to put the month labels inside the graph instead of along the left edge. That made the plot more compact. Because months are intervals of time, I centered the labels within their intervals. Apple (along with the rest of the world) puts labels like this at the start of each interval, but I refuse. Just because graphing software makes it easiest to do it that way doesn’t make it right.

Overall, I prefer the horizontal graph with the yellow sunlight hours, but it was fun figuring out how to make an alternative.

Playing the percentages

January 22, 2026 at 3:19 PM by Dr. Drang

In his excessively long speech to the World Economic Forum yesterday in Davos, Donald Trump did some surprising backtracking. Not the stuff about Iceland Greenland, but on his method of calculating price reductions.

For weeks—maybe months, time has been hard to judge this past year—Trump has been telling us that he’s worked out deals with pharmaceutical companies to lower their prices by several hundred percent. Commentators and comedians have pointed out that you can’t reduce prices more than 100% and pretty much left it at that, suggesting that Trump’s impossible numbers are due to ignorance.

Don’t get me wrong. Trump’s ignorance is nearly limitless—but only nearly. I’ve always thought that he knew the right way to calculate a price drop; he did it the wrong way so he could quote a bigger number. And that came out in yesterday’s speech:

The embedding code is supposed to start the video just after the 47-minute mark. If it doesn’t, that’s where you should scroll to.

If you can’t stand listening to him for even 15 seconds, here’s what he said:

Under my most-favored nation policy for drug prices, the cost of prescription drugs is coming down by up to 90%, depending on the way you calculate. You could also say 5-, 6-, 7-, 800%. There are two ways of figuring that.

Apparently, Trump or his staff decided that this particular audience wouldn’t swallow his usual percentage calculation, so he decided to do it the right way, even though he went on to defend his usual method. Trump has testified that his net worth is whatever he feels it should be on a given day, so why wouldn’t there be more than one way to calculate a price drop?

It’s hard to know what goes on in Donald Trump’s head, but I’m confident of two things:

- He knows that price increases and decreases are opposites. Therefore, if a price jump from $10 to $100 is a 900% increase, then a price drop from $100 to $10 must be a 900% decrease. It’s just logic.

- If you were selling him something and agreed to lower your price from $100 to $10, he would call it a 90% decrease, not a 900% decrease. If he were giving you the same discount (ha!), it would be a 900% decrease. The numbers he uses are whatever sound best to him at the time.

Of course, the key thing about Trump’s deals with drug companies isn’t how percentages are calculated; it’s whether these deals will have any real effect.

Freezing pipes

January 21, 2026 at 4:03 PM by Dr. Drang

The Midwest is expected to have very cold temperatures this weekend, which got me thinking about burst water pipes. Water expands about 9% as it freezes, and a lot of people think it’s pressure from the outward expansion of ice that ruptures pipes, but it’s more complicated than that.

My favorite reference for this phenomenon is this 1996 paper by Jeffrey R. Gordon of the Building Research Council at the University of Illinois. It’s entitled “An Investigation into Freezing and Bursting Water Pipes in Residential Construction,” and it goes through the testing that the BRC did on behalf of the Insurance Institute for Property Loss Reduction.

Why do I have a favorite reference for burst pipes? I used to get hired by insurance companies to investigate burst pipes and the subsequent damage in high-end residences. When the pipe failed in a heated area, it was nice to have this paper to back up my explanation of how freezing in one part of a pipe can lead to failure in another. Also, the report is quite easy to read. There’s not a lot of jargon, and you don’t need much scientific or engineering background to understand it.

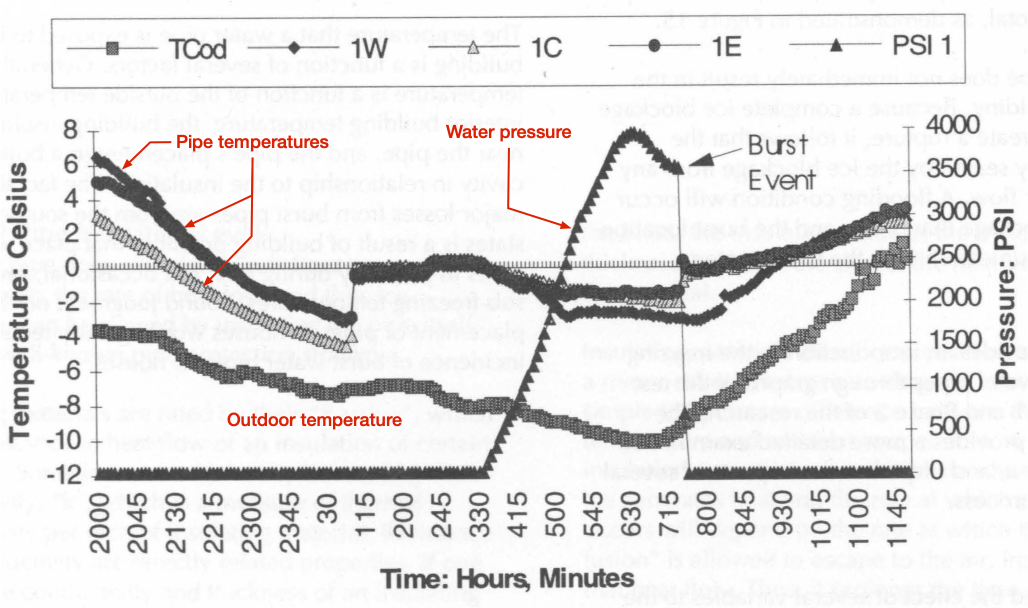

Here’s Figure 15 from the report, which graphs the data collected during the testing of a 3/4″ copper pipe running through an unheated attic. The pipe was instrumented with thermocouples to capture its temperature at three locations and a pressure gauge to capture the water pressure inside it. The red annotations are mine. As you can see, the pressure rose to about 4,000 psi, at which point the pipe bulged—that’s the drop in pressure as the pipe increased in diameter and decreased in wall thickness—and then burst.

The best explanation of what happened in the test—and what commonly happens in real-world pipe bursts—comes from the report itself:

This shows the central, and often least understood, fact about burst water pipes: freezing water pipes do not burst directly from physical pressure applied by growing ice, but from excessive water pressure. Before a complete ice blockage, the fact that water is freezing within a pipe does not, by itself, endanger the pipe. When a pipe is still open to the water system upstream, ice growth exerts no pressure on the pipe because the volumetric expansion caused by freezing is absorbed by the larger water system. A pipe that is open on one end cannot be pressurized, and thus will not burst.

Once ice growth forms a complete blockage in a water pipe the situation changes dramatically. The downstream portion of the pipe, between the ice blockage and a closed outlet (faucet, shower, etc.) is now a confined pipe section. A pipe section that is closed on both ends can be dramatically pressurized, water being an essentially incompressible fluid. If ice continues to form in the confined pipe section, the volumetric expansion from freezing results in rapidly increasing water pressure between the blockage and the closed outlet. As figure 15 shows, the water pressure in a confined pipe section can build to thousands of pounds per square inch.

Read that second paragraph again. It’s really a perfect explanation of how, for example, a pipe or joint under a bathroom sink can fail even though that part of the pipe was never exposed to freezing temperatures. It’s the ice buildup in the pipe elsewhere—typically in an unheated area on the other side of the drywall—and the continued growth of ice in the isolated zone between that blockage and the faucet at the sink that leads to a huge increase in pressure. The pipe will fail at whatever point is weakest within that zone.

Which leads to some common advice given when temperatures are going to drop.

- For sinks up against an outside wall, leave the cabinet doors open so the warm air of the house gets a chance to circulate around the pipes. You want them to get as much exposure to warm air as possible so they can conduct that heat to the colder parts on the other side of the drywall.

- Open faucets that are against an outside wall and let them drip. I’ve never done this because I added extra insulation around and on the cold side of my pipes many years ago, but it can help. Not, as some people say, because moving water doesn’t freeze (have they never seen a river frozen over?) but because a slightly open valve prevents the buildup of pressure shown in Figure 15. As the report says, “A pipe that is open on one end cannot be pressurized, and thus will not burst.”

Belaying follow-up

January 20, 2026 at 4:46 PM by Dr. Drang

At the end of last week’s belaying post, I said we’d look into the condition in which the climber and belayer don’t weigh the same. And we will. But first, I want to talk about stretchy ropes.

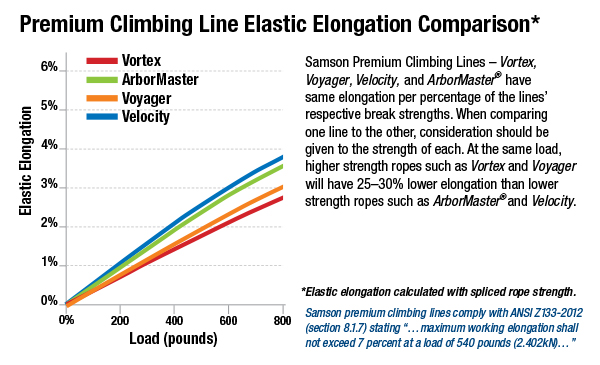

One of my assumptions in the last solution was that the rope connecting the climber and the belayer was inextensible. Now, no ropes are truly inextensible, but I thought it was a reasonable assumption, at least for a first-pass solution. But Rob Nee (via Mastodon), Dirk KS (also via Mastodon), and Kenneth Prager (via email) thought the extensibility of climbing ropes was worth discussing. Dirk KS even sent me a link to the Samson Rope Technologies page that includes this nice graph of its ropes’ compliance:

(If you’re an engineer, you’re used to seeing load-deflection curves with the load on the vertical axis and deflection on the horizontal axis. Be aware that this one is drawn the opposite way.)

I can certainly understand why climbers consider their ropes’ compliance to be important: it makes for a more gentle stop at the end of a fall. For our purposes, what’s important is the potential energy absorbed by the rope as it stretches. If the rope is linearly elastic, the potential energy in a rope that extends by an amount x from its natural length is

where k is the stiffness of the rope and F is the tension. The Samson graph tells us that their ropes are linearly elastic for loads of up to about 400 lbs, so let’s use this equation and see where it gets us.

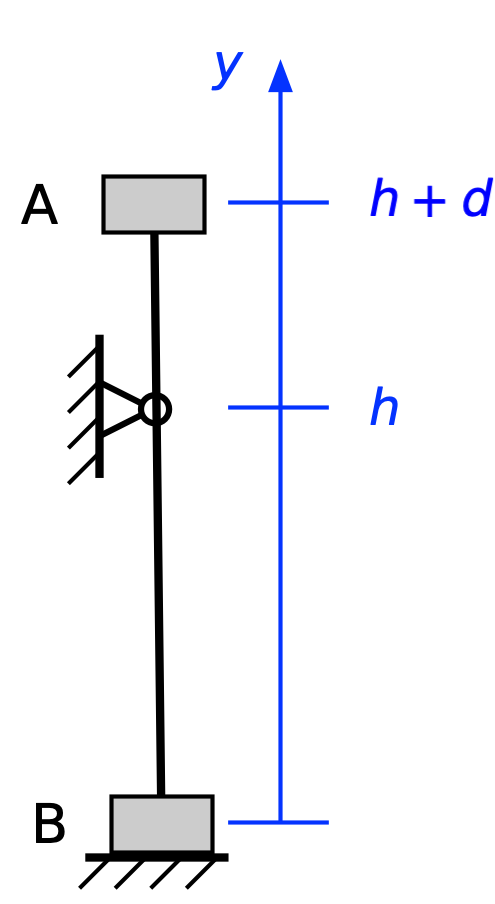

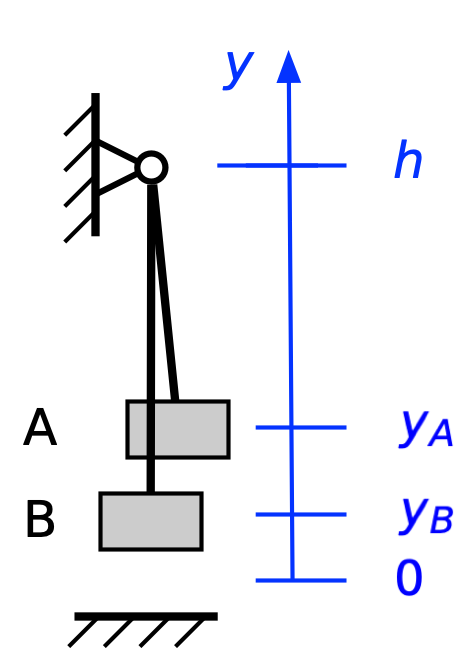

You may recall that Prof. Allain did some motion analysis of the video and came to the conclusion that the climber was about 7.2 m above the belayer when he started his fall. I took this value and some scaling of the video frames I showed in the previous post to estimate the following values:

- Length of rope (L): 24 ft.

- Height of loop (h): 18 ft.

- Initial distance of climber above loop (d): 6 ft.

I’ll also assume the climber and belayer each weigh 150 lbs. These are rough, rounded estimates because I don’t feel greater precision is warranted.

When the climber and belayer come to a halt and are just hanging there, the tension in the rope is equal to each man’s weight: 150 lbs. According to the Samson chart, the more compliant ropes will stretch about 0.75% under this load, which means the rope will stretch

So the elastic energy in the rope is

The gravitational potential energy lost during the initial drop of twelve feet by the climber (which is when the rope first becomes taut) is

The energy that goes into stretching the rope is small potatoes compared to this, so it’s not unreasonable to ignore it in our energy accounting system.

Let’s move on to consider unequal weights. We’ll say the climber has a mass of m, as before, but now the mass of the belayer is βm. As before, the potential energy before the climber falls is

and there’s no kinetic energy:

When the rope becomes taut (we’re assuming an inextensible rope again), the potential energy has dropped to

so the kinetic energy must be

From this point on, the rope keeps climber A and belayer B moving in concert, so

and the change in potential energy will be

Ignoring frictional losses, the change in kinetic energy will be

Now we have three situations to consider:

- means and (without friction) the movement never stops.

- means and (without friction) the movement never stops.

- means and the movement might stop, at least momentarily, even without friction.

The second condition is what we covered last time, so I won’t repeat that.

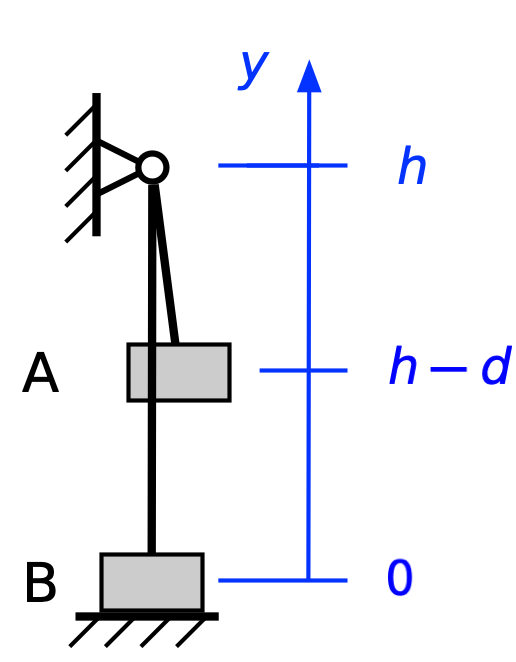

For the third condition, where the belayer weighs more, the system might stop momentarily with the belayer at his highest point and the climber at his lowest, even if there’s no friction in the system. If and where this happens depends on the specific values of β, h, and d. The key concern is whether the climber hits the ground before this momentary stop occurs.

To me, the first condition is the most interesting. It says that the system won’t stop if the belayer weighs less than the climber. In fact, if there’s no friction in the system, the climber would go down to the ground even if the two started hanging statically at the same elevation. But the fact is, lighter belayers can safely control heavier climbers (Kenneth Prager told me he often belays his son, who outweighs him by over 50 lbs). You can see that in this video from the American Alpine Club:

In this video, the rope is running through several carabiners; in the subject video, it appears to be running through just one. Either way, this way of using the friction of a rope running over a stationary curved surface to control movement has been known for ages. It’s called the capstan problem, and it’s covered in the friction section of most elementary engineering mechanics classes.

Update 20 Jan 2026 5:34 PM

Gus Mueller (developer of Acorn) is a climber, and he showed me that the rope in the subject video passes through two carabiners, not one. I have the top one identified correctly; the lower one is about a body length below the top one. The second carabiner doesn’t affect any of the calculations, but it does give another place for friction to do its job.

At this point, longtime readers are expecting me to go through the capstan problem, but really longtime readers know I already did that back in 2010. Oddly enough, that post was inspired by my acting as a belayer at my younger son’s school while his fourth-grade gym class did a rock-climbing unit. That son will be visiting me this weekend; he’s coming into town on a business trip for client meetings in the area early next week. I’m still trying to figure out how a fourth-grader has clients.