Shaking the rust off

March 15, 2014 at 12:04 AM by Dr. Drang

I’m going to use the fooforaw over Neil Young’s Pono project as a jumping-off point for a series of posts on vibration analysis. I know I’ve said this before, but in the immortal words of Bullwinkle, “This time for sure!” I need to stretch my analytical muscles here a little more, lest they atrophy.

I don’t intend to debunk Pono’s high resolution claims. Many people have already done that—you could check out Kirk McElhearn for a good example. Instead, I want to start with the vibration of simple mechanical systems and build up to the more complex systems that we use to produce, and reproduce, sound and music. It’s going to take several posts, and they’ll probably be spread out over a period of months, so if you come here for oddball scripts or Apple-related bitching there’ll still be stuff for you.

I will, however, indulge in one small bit of debunking. Neil Young is 68 years old. Even if he had taken good care of his ears, even if he had lived in an anechoic chamber his whole life, his hearing wouldn’t be good enough at the age of 68 to pick out the extreme subtleties that Pono is supposed to provide. And of course, Neil didn’t limit his exposure to loud sounds.

Because I am myself something of a relic, I remember seeing this trailer for Rust Never Sleeps in the summer of 1979. It was the loudest thing I’d ever heard in a theater. If you were in a multiplex, you could hear it from two theaters away. When a man who spent his youth playing through amplification like this tells me he needs his music sampled at 96 kHz, I am, shall we say, skeptical.

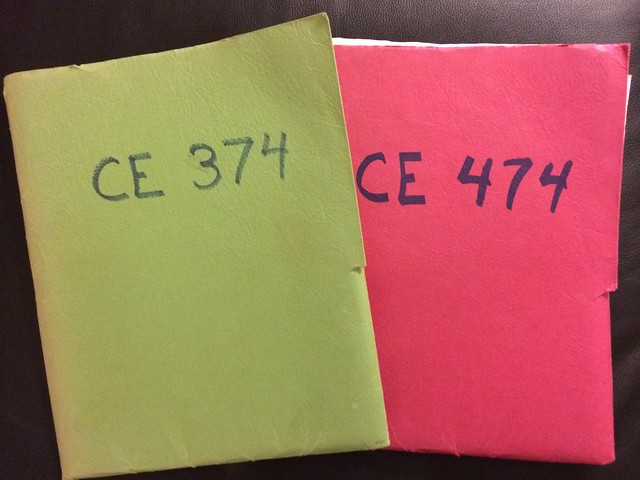

To help me write these posts, I pulled out some reference material from my library at work, including the class notes I wrote while taking a couple of vibration analysis classes in graduate school.

What’s funny about this is:

- These notes are 30 years old, but I keep them around because I still refer to them occasionally and have throughout my professional career. I have distinct memories of certain problems that were covered in these classes, and my notes on their solution speak to me more clearly than any textbook.

- I instinctively went to these notes instead of the lecture notes I wrote for a vibrations class I taught. This bothers me a bit because my lecture notes are definitely better organized than these are (both of these classes were taught by Art Robinson, a brilliant guy but very scattered). For some reason, though, these are the notes I feel more comfortable with.

All of my grad school notes are in folders like these on one of my bookshelves. They aren’t kept in any particular order, and you can’t see the course numbers when they’re on the shelf, and yet I have no trouble picking them out because I remember the color of the folder I used for every one of my classes. Each semester, I used a different color for each class, and those colors are burned into my brain. Now, it’s true that I have a few red folders and a few greens—these folders came in only about a half-dozen colors—but that means I usually grab the one I want on the first or second try.

Color is a strangely effective mnemonic for me. I remember textbooks by color, too. When a colleague asks me if I have a reference for a particular type of problem, I’ll usually answer with something like “Look for a blue book with red lettering. It should be in the second bookshelf about halfway down.”1

Looking at my alma mater’s course listing, I see that these classes have undergone a sort of course-level inflation. CE 374 is now CEE 472, and CE 474 is now CEE 573. I’m pretty sure there were no 500-level courses in my day. Digging a bit deeper, I see that they’re now taught by a classmate of mine. Time flies.

-

Titles of textbooks in my field are so similar as to be useless. How can anyone distinguish between Mechanics of Materials, Principles of Mechanics of Materials, and Advanced Mechanics of Materials? Authors are a much better differentiator, but when you’re halfway across the room from the bookshelf, there’s nothing like color to focus your attention in the right spot. ↩