Apple Watch estimates

July 8, 2022 at 8:36 PM by Dr. Drang

In the Rumor Roundup segment of this week’s episode of Upgrade (starts about 32 minutes in), Jason and Myke talk about the temperature sensor that’s expected—according to Mark Gurman—to appear on the next generation of Apple Watches. The sensor isn’t going to take the temperature of the air; it’s going to take the temperature of you through contact with your wrist. According to Gurman,

The body-temperature feature won’t give you a specific reading—like with a forehead or wrist thermometer—but it should be able to tell if it believes you have a fever. It could then recommend talking to your doctor or using a dedicated thermometer.

Myke wasn’t happy with this. He wanted the actual temperature. Jason’s argument was that Apple wouldn’t want to give its temperature measurement because it probably wouldn’t match the temperature you’d get with an oral thermometer. Apple can avoid complaints that the Watch’s temperature values are inaccurate by never giving you a specific value, but still provide useful information by tracking your temperature over a period of time and putting up warning whenever is gets unusually high or low.

Jason’s argument is persuasive. It’s true that Apple already uses the Watch to provide estimated values for certain health data and doesn’t seem to worry about backlash. But there’s a reason for that.

Because I was out for a morning walk while listening to Upgrade, the estimated value that came to mind was VO₂ max, which you can see in the Cardio Fitness section of the Health app. VO₂ max is your maximum volume rate of oxygen intake, normalized by your body mass. It’s expressed in milliliters per minute per kilogram, and Apple gives you the value to the nearest tenth.

The proper measurement of VO₂ max involves putting you on a treadmill or stationary bike, covering your face with a mask and hose to measures your oxygen intake, and making you run or pedal at increasing speed until your oxygen intake maxes out. This is known as cardiopulmonary exercise testing, or CPET. Because the Apple Watch can’t do CPET, it estimates your VO₂ max by tracking your speed and heart rate (and possibly some other things) during an outdoor walk or run and then applying some formula to the sensor readings.

What formula? I don’t know. I’m pretty sure it isn’t one of the formulas described in the Wikipedia article on VO₂ max, because if it were, Apple wouldn’t have bothered publishing a paper on the study it ran to develop its estimate.

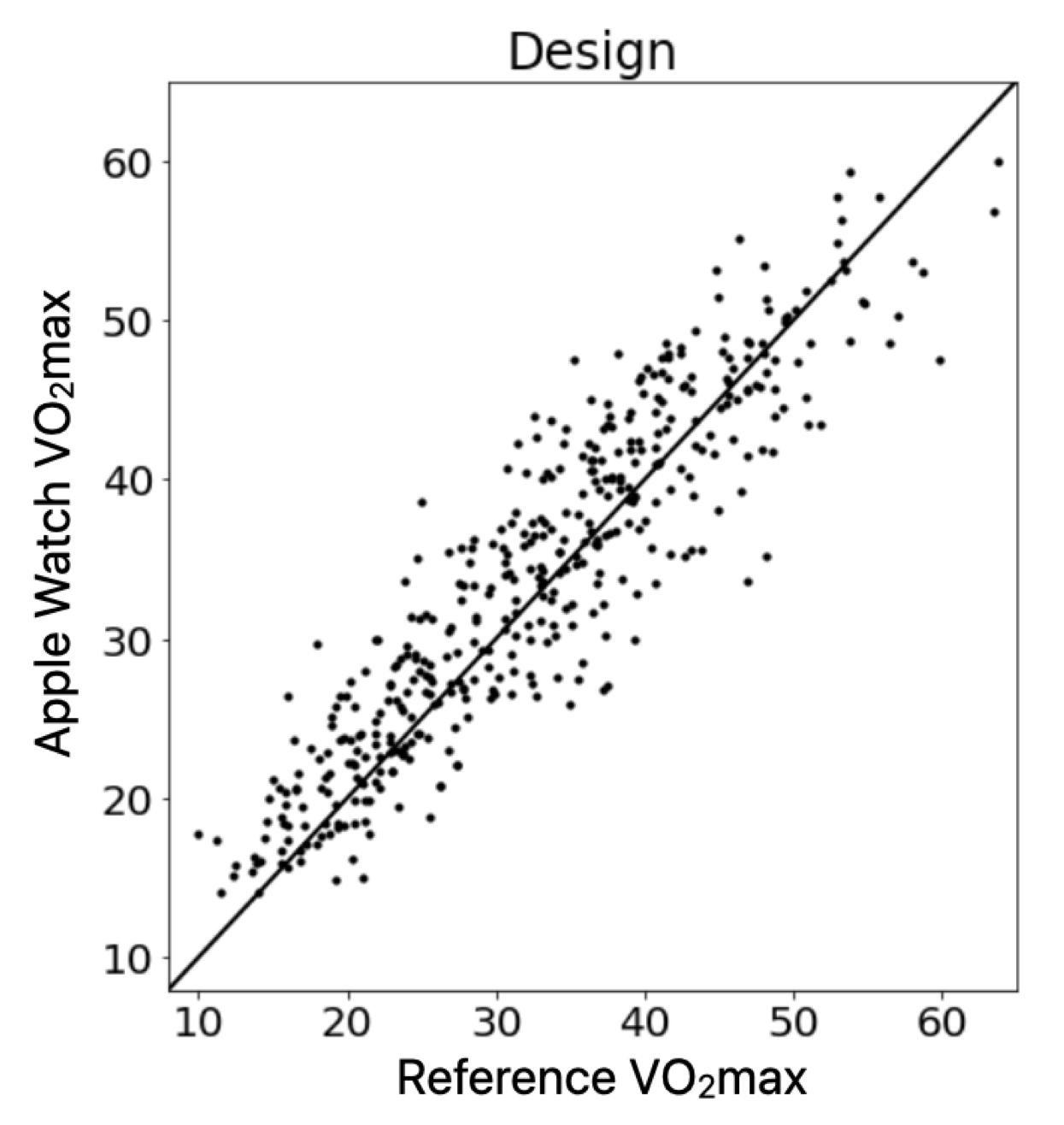

Basically, Apple gathered a group of about 500 people, tracked their exertion during outdoor walks and runs with an Apple Watch, and periodically measured their VO₂ max via CPET. From this, they came up with a formula that fit the sensor data to the CPET results. Apple’s paper doesn’t tell us the formula, but it does give us a graph that shows how good the fit is.

The graph should have a 1:1 ratio, but we’ll ignore that.

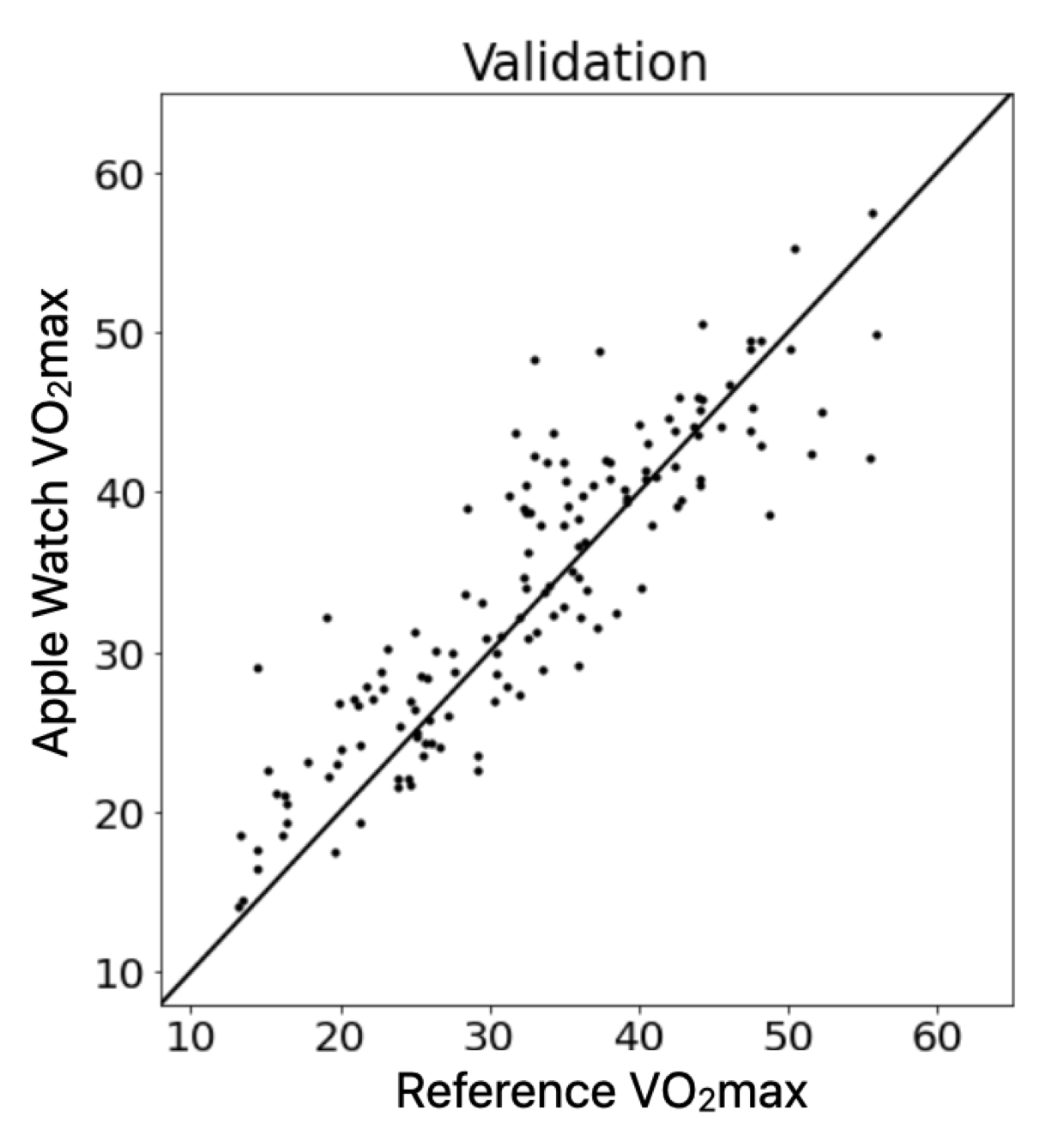

With the formula developed through those 500 people, Apple then tested another 200 people to make sure the formula wasn’t super-specific to the original group. The scatter plot for this validation group looks pretty much like the one for the design group.

Presumably, Apple could do—and probably has done—a similar study to correlate properly measured body temperatures with the readings from the upcoming Watch’s temperature sensor. It could use that study to provide an actual temperature value instead of just a high/low warning.

But look at the spread of the data in those graphs. Given the limited information it’s working from, the VO₂ max estimate looks decent as a population average, but for individuals, the spread can’t be ignored. My Watch tells me I’m at about 40 ml/min/kg, but these graphs say I could be ±10 from that. That’s huge.

Which fits in with Jason’s argument. Despite the spread, Apple’s not really inviting criticism by giving a specific value for VO₂ max—it’s an obscure measurement, hard to check, and the people who are interested in it know perfectly well that the elementary data available to the Watch can’t be expected to provide a highly accurate estimate. But body temperature is both familiar to everyone and easily checked. Imagine how many “Tempgate” YouTube videos would appear with young white men in backward baseball caps waving their Watches and thermometers to the camera. “Yo, check this out! Not even close! Hit that bell!”

The thought of it makes me glad my Apple Watch doesn’t monitor blood pressure.