Belaying follow-up

January 20, 2026 at 4:46 PM by Dr. Drang

At the end of last week’s belaying post, I said we’d look into the condition in which the climber and belayer don’t weigh the same. And we will. But first, I want to talk about stretchy ropes.

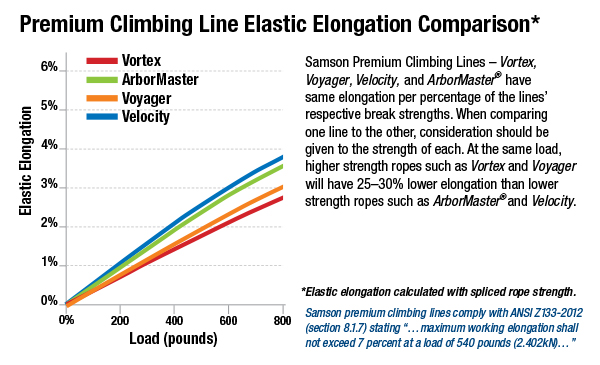

One of my assumptions in the last solution was that the rope connecting the climber and the belayer was inextensible. Now, no ropes are truly inextensible, but I thought it was a reasonable assumption, at least for a first-pass solution. But Rob Nee (via Mastodon), Dirk KS (also via Mastodon), and Kenneth Prager (via email) thought the extensibility of climbing ropes was worth discussing. Dirk KS even sent me a link to the Samson Rope Technologies page that includes this nice graph of its ropes’ compliance:

(If you’re an engineer, you’re used to seeing load-deflection curves with the load on the vertical axis and deflection on the horizontal axis. Be aware that this one is drawn the opposite way.)

I can certainly understand why climbers consider their ropes’ compliance to be important: it makes for a more gentle stop at the end of a fall. For our purposes, what’s important is the potential energy absorbed by the rope as it stretches. If the rope is linearly elastic, the potential energy in a rope that extends by an amount x from its natural length is

where k is the stiffness of the rope and F is the tension. The Samson graph tells us that their ropes are linearly elastic for loads of up to about 400 lbs, so let’s use this equation and see where it gets us.

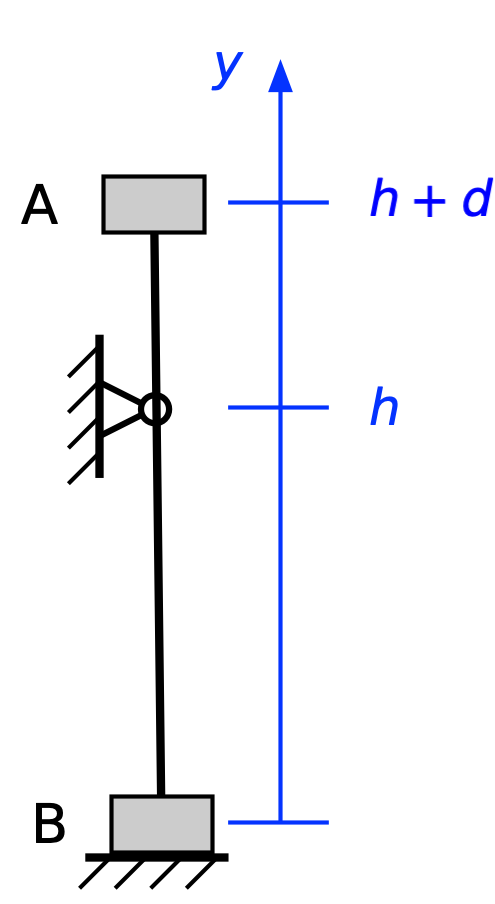

You may recall that Prof. Allain did some motion analysis of the video and came to the conclusion that the climber was about 7.2 m above the belayer when he started his fall. I took this value and some scaling of the video frames I showed in the previous post to estimate the following values:

- Length of rope (L): 24 ft.

- Height of loop (h): 18 ft.

- Initial distance of climber above loop (d): 6 ft.

I’ll also assume the climber and belayer each weigh 150 lbs. These are rough, rounded estimates because I don’t feel greater precision is warranted.

When the climber and belayer come to a halt and are just hanging there, the tension in the rope is equal to each man’s weight: 150 lbs. According to the Samson chart, the more compliant ropes will stretch about 0.75% under this load, which means the rope will stretch

So the elastic energy in the rope is

The gravitational potential energy lost during the initial drop of twelve feet by the climber (which is when the rope first becomes taut) is

The energy that goes into stretching the rope is small potatoes compared to this, so it’s not unreasonable to ignore it in our energy accounting system.

Let’s move on to consider unequal weights. We’ll say the climber has a mass of m, as before, but now the mass of the belayer is βm. As before, the potential energy before the climber falls is

and there’s no kinetic energy:

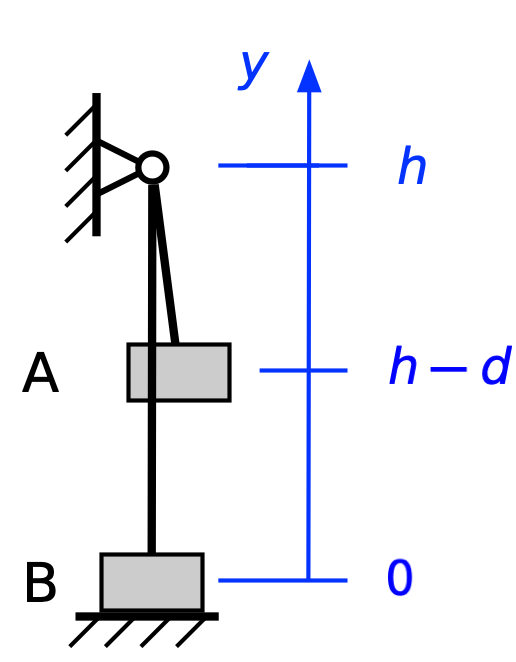

When the rope becomes taut (we’re assuming an inextensible rope again), the potential energy has dropped to

so the kinetic energy must be

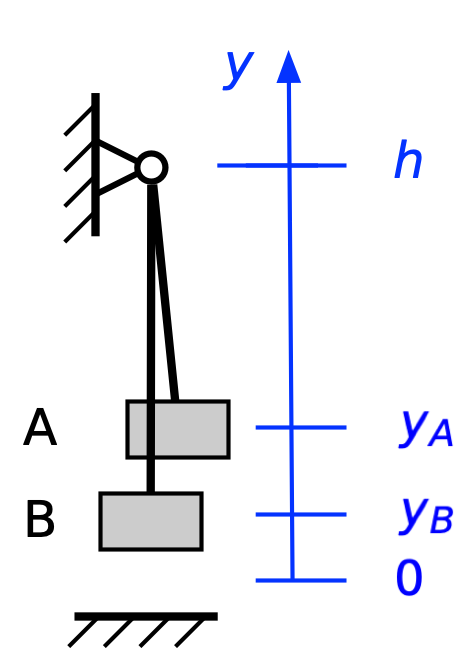

From this point on, the rope keeps climber A and belayer B moving in concert, so

and the change in potential energy will be

Ignoring frictional losses, the change in kinetic energy will be

Now we have three situations to consider:

- means and (without friction) the movement never stops.

- means and (without friction) the movement never stops.

- means and the movement might stop, at least momentarily, even without friction.

The second condition is what we covered last time, so I won’t repeat that.

For the third condition, where the belayer weighs more, the system might stop momentarily with the belayer at his highest point and the climber at his lowest, even if there’s no friction in the system. If and where this happens depends on the specific values of β, h, and d. The key concern is whether the climber hits the ground before this momentary stop occurs.

To me, the first condition is the most interesting. It says that the system won’t stop if the belayer weighs less than the climber. In fact, if there’s no friction in the system, the climber would go down to the ground even if the two started hanging statically at the same elevation. But the fact is, lighter belayers can safely control heavier climbers (Kenneth Prager told me he often belays his son, who outweighs him by over 50 lbs). You can see that in this video from the American Alpine Club:

In this video, the rope is running through several carabiners; in the subject video, it appears to be running through just one. Either way, this way of using the friction of a rope running over a stationary curved surface to control movement has been known for ages. It’s called the capstan problem, and it’s covered in the friction section of most elementary engineering mechanics classes.

Update 20 Jan 2026 5:34 PM

Gus Mueller (developer of Acorn) is a climber, and he showed me that the rope in the subject video passes through two carabiners, not one. I have the top one identified correctly; the lower one is about a body length below the top one. The second carabiner doesn’t affect any of the calculations, but it does give another place for friction to do its job.

At this point, longtime readers are expecting me to go through the capstan problem, but really longtime readers know I already did that back in 2010. Oddly enough, that post was inspired by my acting as a belayer at my younger son’s school while his fourth-grade gym class did a rock-climbing unit. That son will be visiting me this weekend; he’s coming into town on a business trip for client meetings in the area early next week. I’m still trying to figure out how a fourth-grader has clients.