Weighing in

September 26, 2020 at 8:06 AM by Dr. Drang

In yesterday’s post, I mentioned that it took me a year to finally get around to writing a script I’d been thinking about. Today’s post is one whose seed was planted almost two years ago.

In October 2018, Myke Hurley and Stephen Hackett were in Chicago for a Relay FM event that I attended. During the event, they recorded this episode of Ungeniused, their podcast about weird articles on Wikipedia. In honor of the city they were in, the article they chose was “Raising of Chicago,” which describes how, in the 1850s and 1860s, the roadways and buildings of the city were elevated as much as six feet to get them up out of the muck and allow decent drainage of both stormwater and wastewater.

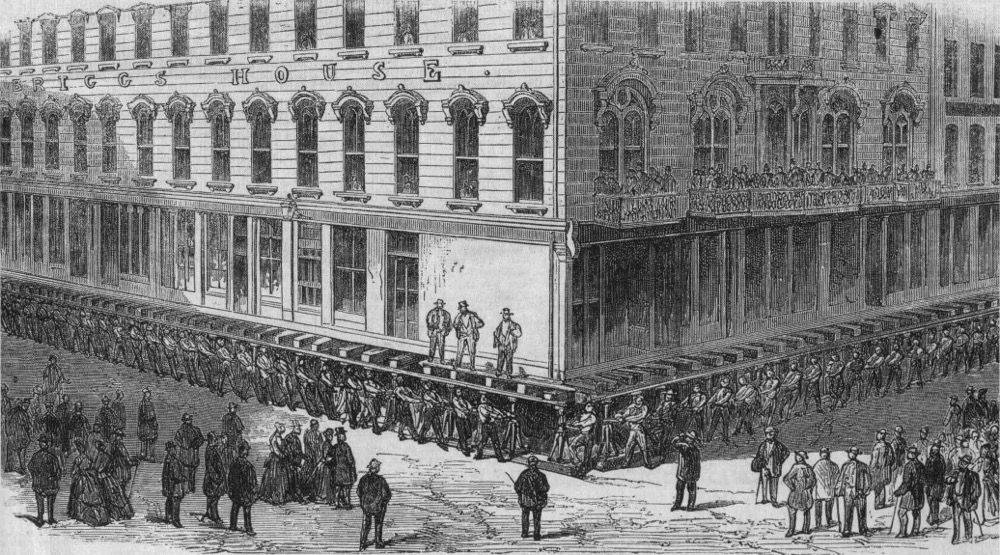

The roadways were easy because you don’t really lift a street; you just add a bunch of fill and build a new road on top of that. But substantial buildings had to be jacked up to keep their ground floors from becoming basements. Here’s an image from the article of a large team of men doing just that.

One of the advantages of blogging over podcasting is you get to include cool pictures like this.

As they were describing the process, Myke and Stephen mentioned the weights of some of the buildings that were lifted, and Stephen asked, “How do you estimate the weight of a building?” After the recording, I told him that the weights of significant buildings are always known by the people who build them. I further said that I would write a post about it. And to prove that I’m a man of my word, here I am… two years later.

(Another advantage of blogging—at least if you don’t have advertisers to satisfy—is that you’re not on a schedule.)

There are two good reasons architects and engineers know the weights of the buildings they design: economic and structural.

The economic reason is simple. Buildings are made primarily from commodity products—things that are sold by weight or volume. When you buy the steel, concrete, stone, masonry, wood, plaster, tile, glass, etc. that your building is made from, you are, in effect, buying your building by the pound. That was as true in 1850 as it is today.

The structural reason is nearly as simple as the economic one. The building has to stand up, which means that each part has to carry both its own weight and the weight of all the parts it supports. The top floor has to carry its own weight and that of the roof. The next floor down has to carry its own weight and that of the top floor and roof. And so on down the building. Ultimately, the entire weight of the building and its contents passes through the foundation and into the soil. The designer has to know what that weight is in total and how it’s distributed among the columns and walls of the building; otherwise, the foundation will crack or sink into the soil.

In fact, what you need to know about the weights and their distribution in order to design the building is exactly what you need to know if you want to jack that building up. The parts of the foundation that had to be extra large or extra strong because they carry more weight will also need more or larger jacks to lift it.

It can be difficult in older buildings to know what all these weights are because the plans have been discarded or misplaced. But that wasn’t a problem in the Chicago of 1850s. There simply were no old buildings back then—not any of significant size, anyway. Chicago was a very young city.

In summary, knowing the weight of a building goes hand in hand with designing it, because it’s a critical part of the building’s cost and its ability to stand up.

So there you go. Better late than never. Speaking of which…

If you’re like me and put things off, you haven’t made your donation to St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital yet. You’ve been hearing about it, of course, on the podcasts you listen to, and you’ve told yourself you’re going to do it. But while September is getting long in the tooth, it’s not over yet, and your donation will still help the families that rely on St. Jude’s and still count toward Relay’s fundraising goals for the month.

Stephen will appreciate your donation even more than knowing how much a building weighs.