Fixing a physics problem

January 14, 2026 at 2:33 PM by Dr. Drang

I’ve been bothered by this little physics problem for a couple of days. It appeared on Rhett Allain’s Medium site on Monday, and he linked to it on Mastodon. Prof. Allain teaches at Southeastern Louisiana University and writes on physics for Wired. I like reading his stuff, but this time he misses the main feature of the problem he’s trying to solve. So…

The problem is based on this video he ran across on Threads. It shows a rock climber slipping and being halted in his fall by the rope that connects him and his belayer. Here are a few frames from the video (you may want to zoom in):

The left frame is when the climber slips and starts to fall. The rope that connects him to the belayer on the ground passes through a metal ring that the black arrow is pointing to. The middle frame is when the rope becomes taut and the belayer starts being pulled up. The right frame is where the simple part of their motion stops. They come together and start using their feet against the cliff; they also start swinging sideways. Elementary physics is not going to help us describe the motion after this.

You might pick slightly different frames for each of these points, but I don’t think we’d be too far off from one another.

Prof. Allain idealizes the situation this way:

- The climber and belayer start at rest.

- The climber and belayer end at rest at the same elevation.

- The climber and belayer weigh the same.

- There is no energy lost through friction as the rope passes through the ring.

With these assumptions, he calculates that the final elevation of the climber and belayer is half the original elevation of the climber, an answer that he immediately recognizes as wrong.

You might think that my objection to his solution is Assumptions 3 and 4, but I have no problem with either of them. Even if you know they’re wrong, using simplifying assumptions like this is usually a good way to start. You can always add complications after you have a handle on the problem.

No, my objection to his solution lies with Assumption 2 and a constraint that he ignores entirely. While the climber and belayer do end up at about the same elevation, it’s not because they come to a halt naturally; it’s because they run into each other. And the elevation they’re at when they come together is determined by the height of the ring and the length of the rope. After the rope becomes taut—and before they collide—the descent speed of the climber and the ascent speed of the belayer are equal. That is a key constraint on the system that any solution must account for.

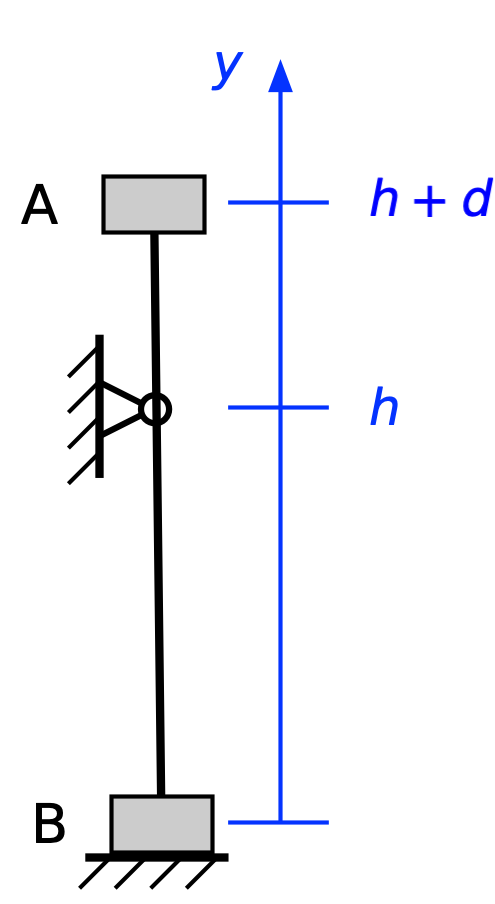

Let’s do this problem with Assumptions 1, 3, and 4. Here’s the starting position:

Our y axis starts at the center of gravity of the belayer, B. The height of the ring is h, and the climber is a distance d above the ring. I’m adding another assumption here: that the belayer is playing out rope as the climber ascends, keeping almost no slack in the rope. That would be the safe way to deal with the rope, and it looks like there’s little slack in the rope before the fall. You can see that if you look at the video itself instead of my reduced-size frame grabs. I should mention that the climber is not directly above the ring, which introduces some angles that I’m going to ignore. Including them would not change the principles of the following analysis but would cloud the principles by making the math more complicated.

The gravitational potential energy at this point is

where m is the mass of the climber and g is the acceleration due to gravity. As Prof. Allain says, there’s no kinetic energy in the system before the climber falls: .

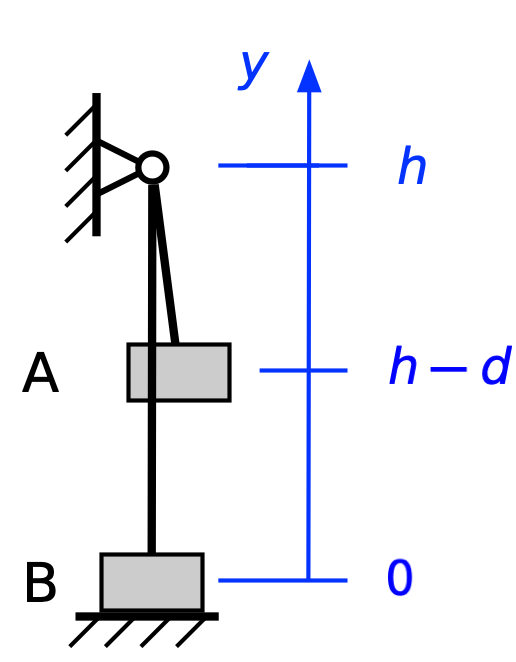

Now let’s consider the point at which the rope becomes taut again. The climber has been in free fall between the initial position and this point:

Let’s not worry about horizontal positioning here. Now the potential energy is

and because the total energy is conserved, the kinetic energy must be

which is obviously a positive value. We could, at this point, calculate the downward velocity of A, but we don’t need that information to continue the analysis.

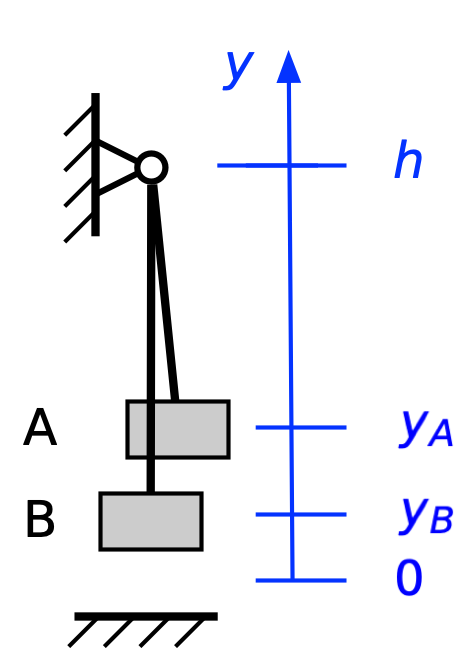

From now on, the constraint of the rope comes into play. Here’s a later position:

We’ll assume the rope is inextensible, which means

where L is the length of the rope. Rearranging, we get

The right-hand side of this equation is constant, so if we take the derivative of each side with respect to time, we get

What this means is that for every time interval from the point at which B lifts off the ground,

Since the two men are of equal weight,

so the potential energy remains constant after B lifts off the ground.

Since the potential energy remains constant, the kinetic energy must remain constant, too, and the two will continue their motion. To come to a stop, they must remove kinetic energy by way of

- a collision with each other;

- striking/rubbing the cliff wall; or

- friction of the rope against the ring.

All three of these can play a role.

To me, the key feature of this problem is the constancy of the gravitational potential energy after the rope becomes taut, and that constancy comes from the constraint provided by the rope. Without considering that constraint, you cannot explain the behavior.

What if the two men don’t weigh the same? If the climber weighs more, the potential energy decreases as he moves down and the belayer moves up, which means the kinetic energy increases. If the belayer weighs more, the opposite is true. We’ll look at this more complicated problem in a later post.

A complication that’s one step too complicated

January 12, 2026 at 5:47 PM by Dr. Drang

I strained my right thigh and hip this fall doing something, but I don’t know what it was. Eventually, after several weeks of thinking it would work itself out, I decided it wouldn’t and started going to physical therapy. Several of the exercises I’m supposed to do at home involve getting into a stretching position and holding it for 30 seconds. For a while, I counted off the time. Then I switched to telling my nearby HomePod Mini to set a timer for 30 seconds. That worked well, but I got tired of hearing Siri tell me that it was starting a timer, and the alarm that sounded at the end was too loud.

Recently, I realized that the bottom center complication on my Apple Watch wasn’t being used for anything useful, so I switched it to a 30-second timer.

You’ll notice that the bottom right complication is for the Timer app, which looks like this when I open it:

Using this to start a 30-second timer was fine, but it takes two taps to start the timer: one on the complication and then one on the 30-second button in the app. I figured a complication dedicated to a 30-second timer would give me one-tap access.

You know where this is going, don’t you?

Tapping on the 30-second complication is not like tapping on the 30-second button within the Timer app. Instead of starting the timer, it brings up this screen:

I have to tap the little Play button in the lower right corner of this screen to start the timer. It doesn’t start on its own, nor does it start if I tap the nice big circle with the redundant “0:30 30 sec” written inside it. Which leads to this question:

What in God’s name does Apple think I want to happen when I tap a Timer complication labeled “0:30”?

I remember Patrick Rhone, who used to write the Minimal Mac blog (has it really been a decade since he stopped?), saying that he always told people new to the Mac to just try what they thought should work and it almost always would. Want something saved in a sidebar? Drag it over there. Want some slightly different behavior when using a drawing tool? Hold down the Option key while you use it. Apple trained its users to think like this.

So when I go to the trouble to make a complication that’s specifically for a 30-second timer, I expect it to start the timer when I tap the complication. I don’t expect it to bring up another screen with another button. And I certainly don’t expect the button I now have to tap to be smaller than the one I’d tap if I had started with the generic Timer complication.

I feel bad complaining about small stuff like this. But the point of spending more for Apple products is that its product managers are supposed to complain about the small stuff so it gets fixed before release. Why are the affordances we used to take for granted missing?

Update 13 Jan 2026 11:16 AM

Everyone who commented on this agreed that the complication didn’t work the way it should, but there were some workaround suggestions. The one I like came from Nicholas Riley on Mastodon. He suggested raising the watch to my mouth and saying “30 seconds.” In my testing, saying “set a timer for 30 seconds” or “30-second timer” also works. The key is that I don’t have to preface the command with “Hey, Siri.” Doing so would typically have the request answered by my HomePods, which I do not want for reasons discussed in the original post.

This works because both Nicholas and I have the Raise to Speak setting turned on in Settings→Siri:

This is a setting that I had simply forgotten about. I suspect I’ve never used it before because I’ve always been reluctant to talk to my devices in public. But I don’t do my stretching exercises in public.

Now, if your watch happens to be up near head level already, simply turning it toward your mouth may not be enough to trigger Siri. I’ve had that happen—or not happen. But generally speaking (ha!), this is a good way to avoid Apple’s poor timer complication behavior. In fact, I’m now thinking I don’t need the generic timer complication anymore.

Thanks for the tip, Nicholas!

Will Apple get on the bus?

January 11, 2026 at 9:51 PM by Dr. Drang

Do you remember the Acid Tests? Not Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests; even I’m not old enough to remember those; I only read about them in Tom Wolfe’s book. No, I’m talking about the tests that checked browsers on how well they complied with web standards. Back in the mid-aughts, Apple talked a lot about how well Safari and WebKit did on these tests, in contrast to Internet Explorer. I was reminded of this while listening to the most recent episode of Connected.

In the show, Myke Hurley’s risky pick was that by the end of 2026, Apple will not have shipped Apple Intelligence features equivalent to those shown at 2024’s WWDC. You can use Overcast’s convenient web interface to listen to his pick. The part of his pick that reminded me of the Acid Tests was this, where he explains why he thinks they’ll be delayed furthur:

I think they will not commit to App Intents as the way that [actions across apps] works, and that instead they will move to MCP… They need to go into an open standard that everybody else could potentially use, that there is more incentivization to use, and use that as a way to make this work.

You may think that shifting from a home-grown system to an open standard is not Apple’s way, and it certainly hasn’t been over the past 15 years or so—quite the opposite, in fact. But in the early days of OS X, when Apple was struggling to re-establish the Mac, one of the groups it wanted to appeal to was the growing number of web developers who wanted to work in a standard Unix environment, but one with a friendly face. Remember when System Preferences had a graphical UI for controlling your local Apache webserver? Remember when /usr/bin was filled with interpreters before you installed Xcode? Those were part of the same mindset that touted Safari’s Acid Test score.

This doesn’t mean that Myke is right and that Apple will embrace a standard it didn’t help create. It just means that Apple used to see the value in using standards to catch up when it’s behind. The question is whether it will remember that after so many years of success.

A Zeckendorf table in Python

January 10, 2026 at 5:15 PM by Dr. Drang

After writing this morning’s post, I went down to Channahon for a walk along the I&M Canal towpath. On the drive there and back, I thought about redoing the project in Python instead of Mathematica. It seemed like a fairly easy problem, and it was.

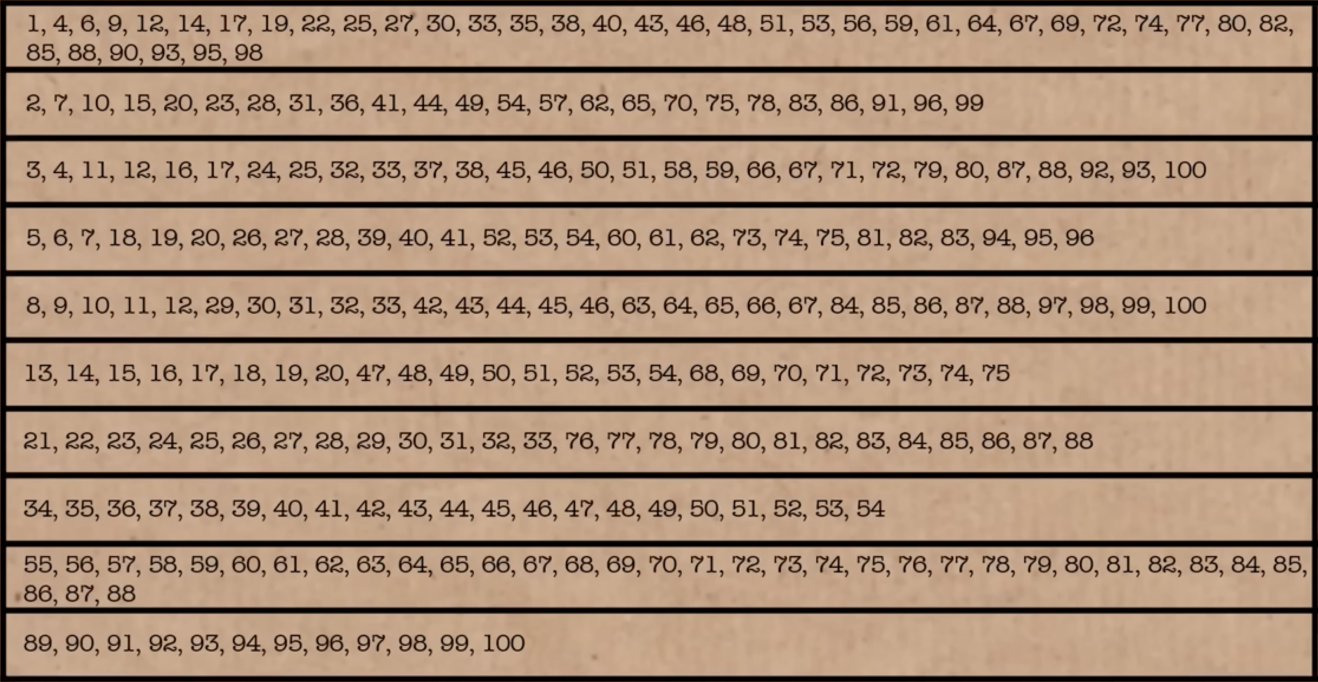

Recall that the goal was to reproduce this table from a recent Numberphile video:

Instead of using someone else’s code for creating the Zeckendorf representation of an integer (examples of which are relatively easy to find), I decided to write my own using the greedy algorithm outlined by Tony Padilla in the video. Here’s the script:

python:

1: #!/usr/bin/env python3

2:

3: from collections import defaultdict

4:

5: def zeck(n):

6: 'Return the Zeckendorf list of Fibonacci numbers for n.'

7:

8: # Greedily subtract Fibonacci numbers from n until zero.

9: z = []

10: left = n

11: for f in reversed(fibs):

12: if (m := left - f) >= 0:

13: left = m

14: z.append(f)

15: return z

16:

17: # Fibonacci numbers less than 100, excluding the initial 1.

18: fibs = [1, 1]

19: while (n := fibs[-2] + fibs[-1]) < 100:

20: fibs.append(n)

21: del fibs[0]

22:

23: # Build the table.

24: ztable = defaultdict(list)

25: for i in range(1, 101):

26: for z in zeck(i):

27: ztable[z].append(i)

28:

29: # Print it.

30: for f in fibs:

31: print(', '.join(str(n) for n in ztable[f]))

32: print()

The greedy algorithm is in the zeck function on Lines 5–15. It assumes the existence of a list of Fibonacci numbers saved in the global variable fibs. It goes through fibs in reverse order. If the current Fibonacci number can be subtracted from the number without going below zero, it is, and it’s also appended to the Zeckendorf representation list. This process is repeated, subtracting—if possible—each Fibonacci number in turn from the remaining difference until we get to the end of the reversed fibs list.

Unlike the ZeckendorfRepresentation function in the Wolfram Language, zeck doesn’t return a list of ones and zeros whose positions are associated with Fibonacci numbers; it returns the Fibonacci numbers themselves. So zeck(50) returns [34, 13, 3].

You probably see some things in zeck that could be made more efficient. Me too. But in a small problem like this, I didn’t think those efficiencies were worth the effort.

Also note that zeck is not a general-purpose function. I wrote it specifically for this script, and it’s built on certain assumptions. The assumptions have to do with how it’s called and how the global fibs list is constructed:

- The argument passed to

zeckis a number small enough that its Zeckendorf representation consists entirely of numbers from thefibslist. - The

fibslist is in increasing order. - The

fibslist does not contain the initial one of the Fibonacci sequence.

Lines 17–21 create the fibs list to meet these conditions. After the deletion on Line 21, it’s

[1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89]

My favorite part of this bit of code is the walrus operator (:=) in Line 19. Apparently, there are people who don’t like the walrus operator. Don’t listen to them.

Lines 23–27 then build the table. In this case, I used a defaultdict called ztable whose keys are the Fibonacci numbers and whose values are the lists of numbers that have that key in their Zeckendorf representation.

Finally, Lines 29–32 print out the values of ztable. Here they are, formatted to fit better in this space:

1, 4, 6, 9, 12, 14, 17, 19, 22, 25, 27, 30, 33, 35,

38, 40, 43, 46, 48, 51, 53, 56, 59, 61, 64, 67, 69,

72, 74, 77, 80, 82, 85, 88, 90, 93, 95, 98

2, 7, 10, 15, 20, 23, 28, 31, 36, 41, 44, 49, 54,

57, 62, 65, 70, 75, 78, 83, 86, 91, 96, 99

3, 4, 11, 12, 16, 17, 24, 25, 32, 33, 37, 38, 45,

46, 50, 51, 58, 59, 66, 67, 71, 72, 79, 80, 87, 88,

92, 93, 100

5, 6, 7, 18, 19, 20, 26, 27, 28, 39, 40, 41, 52, 53,

54, 60, 61, 62, 73, 74, 75, 81, 82, 83, 94, 95, 96

8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 42, 43, 44,

45, 46, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 97,

98, 99, 100

13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51,

52, 53, 54, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75

21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33,

76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88

34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46,

47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54

55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67,

68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80,

81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88

89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100

This matches both the video screenshot above and the list given in this morning’s post.